“Trapping small mammals is a lot like fishing,” says Mike Schrad, bending down to pick up a small, metal box tucked beneath the grass. “Some days you catch a lot, and some days you don’t catch anything.”

We’re standing in a patch of remnant sandhill prairie, and the morning dew is seeping through my hiking boots as I follow Schrad from one trap to the next. He can tell if we’ve caught something without even opening the trap, judging by the weight and the feel of frantic little feet scurrying within.

“This one’s empty,” he says, flakes of oatmeal flying as he snaps the front closed.

“And this one.”

And another.

I’m starting to see what he means about fishing, when Schrad stops ahead of me at a trap. “We’ve got something.” He picks the box up, and in one swift motion, flips the trap door open and tips something tiny, brown, and furry into the mouth of a plastic ziploc bag.

It’s a plains pocket mouse.

Schrad, a Nebraska Master Naturalist and long-time volunteer, is here at The Nature Conservancy’s Platte River Prairies preserve as part of a long-running research project to understand how populations of small mammals are impacted by grassland management.

With any luck, the tiny, wiggly mouse we’ve just caught might tell us something about TNC’s efforts to restore Nebraska’s native prairie.

Pocket Mice on the Prairie

The Platte River Prairies preserve forms a chain of protected grasslands and wetlands along the Platte River as it flows eastward through south-central Nebraska. Since 1988, TNC has restored 1,500 acres of cropland to re-connect fragments of remnant prairie.

The field we’re standing in this morning is a small patch of remnant sandhill prairie. Our boots crunch through grasses — needle-and-thread, little bluestem, sand lovegrass — as we walk across the field. Just a few hundred feet away is Schrad’s second trapping site. To my untrained eye it looks identical to the field we’re standing in, but preserve manager Cody Miller tells us that it was a cornfield years ago.

Prairies need both fire and grazing to flourish, and so much of Miller’s work focuses on managing the preserve through a combination of prescribed burns and cattle grazing. (Elsewhere in the region, TNC is restoring bison to their historic role as plains grazers.)

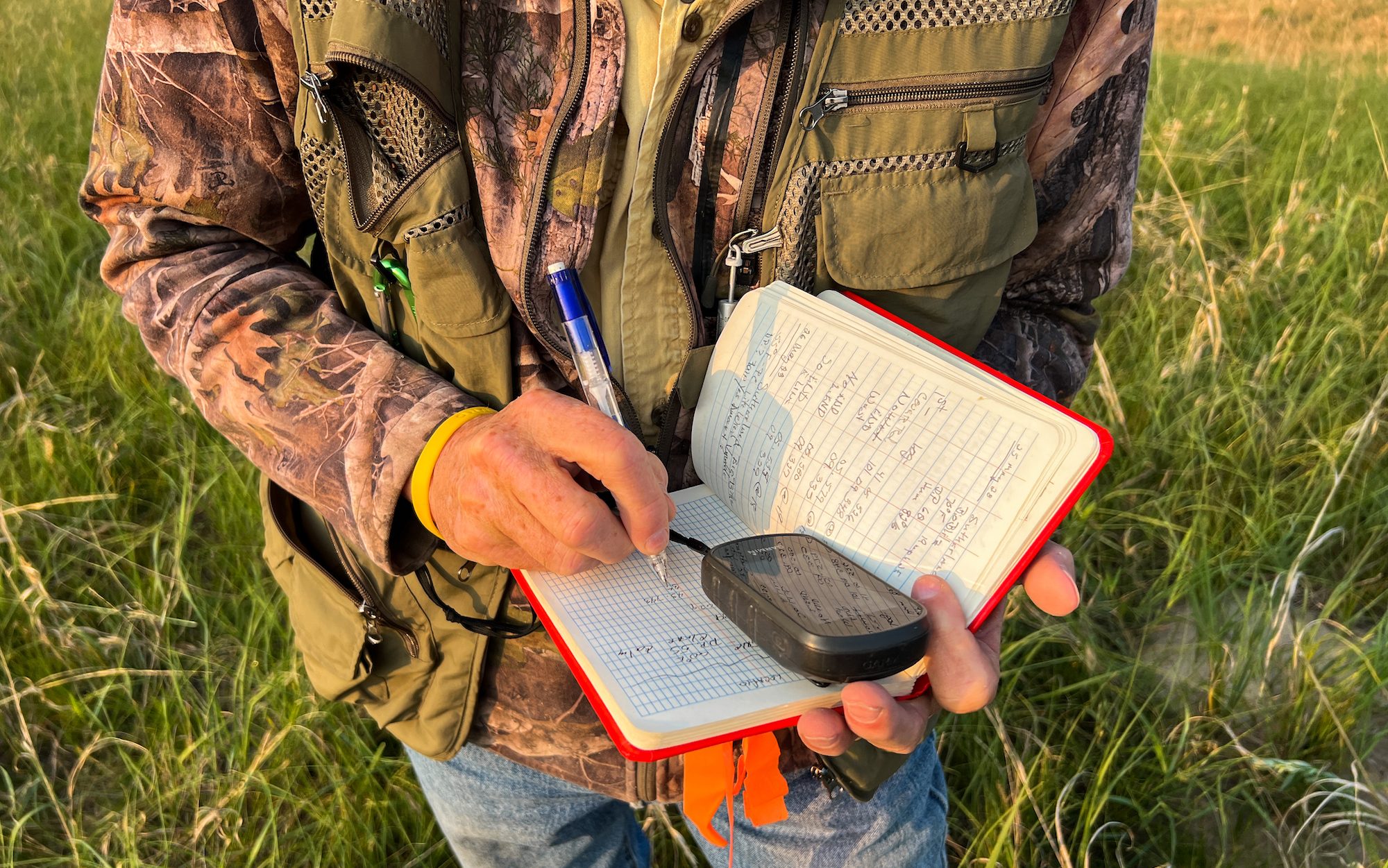

Schrad’s been volunteering his time to trap at the preserve since 2013. He returns here three times a year — spring, summer and fall — to capture small mammals as part of a long-term study to compare how different types of grassland management affect native species, including the little pocket mouse wiggling in his hands.

Schrad deploys the traps at sunset — 40 in the remnant prairie and 40 in the restored — and then returns at dawn to check them. “It’s a bit of a challenge when they graze this area and we trap at the same time,” he says, “because the cows like to dance on my traps.”

“It’s a bit of a challenge when they graze this area and we trap at the same time, because the cows like to dance on my traps.”

Mike Schrad

The little pocket mouse crouches calmly in the plastic bag, its cheeks stuffed full of oatmeal and birdseed that Schrad uses as bait. It’s experiencing what amounts to an alien abduction, but at least it will scurry away with a meal.

“Make sure you get the old-fashioned oatmeal, not the instant oatmeal,” instructs Schrad, as he gently coaxes the mouse to the corner of the bag. “The instant oatmeal gets wet with dew and turns into mush.” The plastic bag is very low-tech, but it lets Schrad handle mammals safely while he records data, inducing the animal’s weight, age, sex, and location of capture. (In a pinch, a takeaway coffee cup works, too.)

This first catch of the day is a plains pocket mouse, one of the species that Schrad and Miller are especially interested in.

Pint-sized and adorable, this seed-eating species depends on native grasslands. It’s named not for its size, but for the two external cheek pouches that it uses to store food. Schrad explains that other rodents cache food inside their mouths, in between their teeth and cheek. But pocket mice have a fully external pocket on each cheek, like a tiny kangaroo pouch.

“This is the western subspecies… that little ear spot is characteristic, and you see the brownish band along the sides,” he adds. “And this study area right here, this is the most common species out here.”

After just two minutes Schrad is done, and it’s time to let the mouse scurry back to its burrow. Releasing it is as simple as resting the open bag on the grass. After a moment or two, the mouse is away, disappearing right beneath our feet.

We walk on, careful not to step anywhere near where we last saw the mouse. It’s on to the next trap, dickcissels and grasshopper sparrows calling in the background as we crunch through the grass.

For Small Mammals, It’s All About Structure

Plains pocket mice aren’t the only species that turn up in Schrad’s traps. Sometimes catches finds grasshopper mice, who are especially wiggly. “They have a habit of marking their territory by chirping, just like a bird,” he says.

What he catches often comes down to the type of habitat he’s trapping in. Western harvest mice sometimes turn up, he says, although they tend to like taller grasses and sometimes build their nests elevated from the ground. Another species that Schrad has yet to catch is a kangaroo rat, which is much larger than the pocket mice and has large hind feet adapted for hopping. “But to hop around in heavy cover like this is difficult… they need clear space, some bare ground.”

When Schrad looks at a grassland, he’s not thinking about individual plant species but about the structure of the habitat. What percent of the ground is covered? How much of it is grass, versus leafy forbs? “Those differences in structure are so important to small mammals,” he says. And differences in structure often come down to different types of management.

Miller has the next trap in hand by the time we catch up to him. “We’ve got something,” he says, as he opens the door and tips the trap over. Only the mammal that plonks down into the plastic bag isn’t a plains pocket mouse. It’s a mass of squirming stripes and spots, and everyone yells in surprise as Schrad laughs.

“It’s a thirteen-lined ground squirrel,” Schrad says, a species that’s considerably larger than a pocket mouse. And feisty. And can nip your fingers through the bag.

Schrad says they’re an unusual catch, because thirteen-lined ground squirrels are diurnal. It likely wandered into the trap shortly after he set it yesterday evening.

After releasing the ground squirrel, we finish checking all 40 traps, closing each of them as we go to avoid catching any wildlife during the heat of the day. Schrad will be back later this evening to open and bait them again, for his second night of trapping.

Our catch for the morning — three pocket mice and a ground squirrel — is a good count for spring, which tends to have a lower catch rate than other times of year. It’s far fewer animals than I expected, something Schrad notes is typical of small mammal studies.

“Getting nothing there is fairly common,” he says, “That’s why small mammal studies take so long. You have to go out, throw a lot of traps down, and keep at it for years. Literally.” He notes a similar study in Kansas that’s been running for three decades.

The other challenge for these types of studies is finding locations that you can return to year after year, he says, and that’s why preserves like Platte River Prairies are so important. Cornfields, restored prairie, and relics of native prairie, all within arm’s reach.

“Having relics like Platte River Prairies provides a pocket of diversity,” Schrad says. “It’s a jewel, it really is.”

And the little mammals scurrying amongst these grasses might seem inconsequential, but, as Schrad says: “You never know what one species is going to add to mankind.”

And you never know what one pocket mouse can tell us about managing prairies.

Kudos to Nature Conservancy volunteers and staff for this valuable work maintaining and studying the prairie remnants and preserves along the Platte. I was, however, sad to read Mr. Schrad’s final comment that a seemingly inconsequential species might be important because of its possible value to mankind. I have served on the boards of several environmental organizations and understand that this formulation is felt to be very important to raise wider support and buy-in for conservation and environmental action. Nevertheless, I have long wished we could just insist that all species have intrinsic value as unique products of evolution and have a right to exist regardless of any use or beauty that humans may find in them. I have been reading a biography of the renowned naturalist, conservationist, and author Gerald Durrell–an early pioneer of captive breeding by zoos for the purpose of rewilding all sorts of creatures, not just the charismatic ones–who felt strongly that homo sapiens was simply one species among all the rest and that, despite or perhaps proved by our current domination and despoiling of the planet, every other creature was our equal in value. He would have been captivated by the pocket mice and the 13-lined ground squirrel. Thank you for this story about them and their protectors. (Please note that I am not criticizing Mr. Schrad; I admire his dedication and work. I just wanted to say that I think it is too bad that we environmentalists and conservationists usually feel we have to justify trying to preserve creatures, plants, and their ecosystems by stressing how useful they could be for humans. I’ve done it too…but we’re actually not the center of the unverse.)