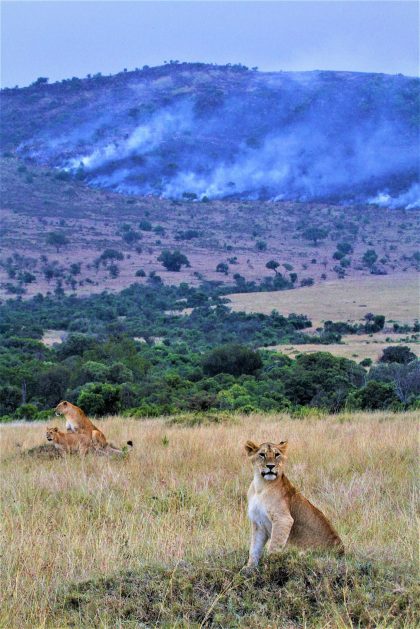

Africa’s grassland ecosystems are home to some of the continent’s most iconic wildlife: lions and elephants, wildebeest and cheetahs, giraffe, and zebra. As demands on the environment increase, protected areas are critical to ensuring that Africa’s wildlife and wild lands remain protected.

But Africa’s protected areas are experiencing a financial crisis, with funding shortfalls in the billions of dollars each year. The COVID-19 pandemic only deepened the crisis by cutting off tourism, which was the major funding source for the majority of Africa’s protected areas.

Now, a new study demonstrates that fire management on Africa’s savannas can generate enough carbon revenue to fill the funding gap for many protected areas, as well as help restore the rangelands health and meet international climate commitments.

Protection Alone Isn’t Enough

The designation of a new national park or protected area is always met with celebration. But the truth is that setting aside land and designating it as “protected” doesn’t automatically guarantee conservation goals are met. All protected areas require management, and that requires a steady stream of funding.

That’s especially true of African protected areas, many of which harbor endangered species that require an additional level of on-the-ground protection, like lions and elephants. Scientists previously estimated that it costs between $1 and 2 billion USD of new funding per year to effectively manage all African protected areas that contain lions.

“Nowhere else do you see such huge human and wildlife populations living in uncomfortable coexistence,” says Geoff Lipsett-Moore, a carbon scientist at The Nature Conservancy. “These protected areas are under massive threat from a growing human population and demands for agriculture, cropping, cattle, and other resources.”

Sustainable financing, he says, will be critical to ensuring that protected areas can safeguard wildlife in the face of these pressures. And fire management across Africa’s savanna grassland could provide a significant part of that funding.

When Grasslands Burn

Savanna grasslands cover 20% of Earth and are one of the world’s most fire-prone ecosystems. But when and how these grasslands burn matters.

Natural fires, sparked by lightning, usually take hold late in the dry season, when high fuel loads allow them to burn intensely over large areas. Large fires release more nitrous-oxide and methane, two of the most potent greenhouse gases (GHGs). (Carbon is emitted, too, but then eventually offset as the grass re-grows.)

Under a GHG-focused fire management program, smaller frequent fires are lit early in the dry season, when there’s less fuel available and the weather prevents large conflagrations. These cooler, less intense fires release less nitrous-oxide and methane. The difference between what is emitted during earlier prescribed burns and typical later natural fires, known as the “abatement potential,” can be sold as carbon credits to generate income for protected area management.

Savanna fire management projects in Northern Australia have resulted in significant funding for indigenous-led conservation, cultural revitalization and a plethora of co-benefits.

Lipsett-More and his collaborators wanted to understand whether similar management could fund large protected areas in Africa. Their earlier research found that 74% of global savanna fire emissions occur in Africa, across 20 least developed countries, suggesting the potential for emissions mitigation — and carbon markets — was significant.

Funding Protected Areas with Fire

Building on their previous research, the team calculated the emissions abatement potential of switching from late-season fires to an early dry season fire management program across 198 protected areas from 19 African countries.

“In addition to abatement, good fire management also increases carbon sequestration in soil, as well as in woody biomass, like shrubs and trees,” explains Nicholas Wolff, a climate change scientist at TNC and author on the paper. “So we also incorporated those carbon benefits into our estimates.”

Their results, published recently in One Earth, show that savanna fire management could generate between $59.6 and $655.9 million USD per year based on a market price of $5 USD per ton. At a higher price of $13 USD per ton, the revenue could be as high as $155.0 million to $1.7 billion USD per year.

Depending on the carbon price, their results show that savanna burning could partially or even substantially reduce the estimated $1-2 billion USD funding shortfall for many African protected areas with lions.

“The value of carbon is only going to go up — there are few bets on the planet you could make that are as sure,” says Timothy Tear, lead author on the research and the director of climate change at the Biodiversity Research Institute. “And now that you have so many companies and nations trying to get to net zero by 2050, or earlier, there is a real incentive to try to find and launch new carbon projects that can help achieve these goals.”

To date, the vast majority of carbon financing has focused on forests, but the study’s authors agree that grasslands ecosystems are a significant untapped opportunity.

Savanna burning can also help build ecosystem resilience by increasing carbon storage in soils. “Increasing soil carbon helps hold moisture longer and cycle nutrients better, both of which result in healthier vegetation and an increased ability to bounce back from drought,” says Tear. That, in turn, will have flow-on benefits to grazing herbivores and their predators. “When you look at building resilience, increases in soil carbon are the best single indication of ecosystem resilience,” Tear adds.

The next step, the authors say, is for countries to start trialing savanna burning projects on the ground, utilizing traditional knowledge from African cultures and learnings from successful projects elsewhere, like northern Australia.

“If we’re going to keep the world in the realm of 1.5 degrees Celsius, then we can’t be fearful of getting out there and making mistakes,” says Lipsett-Moore. “We need to have a greater appetite for risk, be willing to innovate, and test these things on the ground quickly. That’s how we can make really transformative changes for community, culture, and wildlife.”

Interesting and hopeful.

Thank you.