We often think of large mammals as the best known and most beloved among the world’s biodiversity. But even many of the world’s largest (and I would argue, coolest) hoofed mammals remain out of sight and out of mind, even for conservationists.

Yes, almost everyone knows zebras and bison. But what about mountain nyala or serow?

Ten years ago, while on a wildlife trip to India, our national park jeep came around a bend and came across a herd of gaur, wild oxen with large horns and striking colors that can weigh a ton. I excitedly asked our guide to stop. A dream mammal, right in front of us. The guide was surprised: most people just wanted to see tigers. A gaur, for casual wildlife viewers, was just a big cow.

Another “big cow” of the Asian forest, known as the kouprey, is even less known. The kouprey is likely extinct. Relatively recently, some cast doubt whether the kouprey ever existed.

Never existed? Consider this: The kouprey is a large wild animal with spectacular horns that can weigh 1,500 pounds. It’s Cambodia’s national animal. While mysterious, it’s no bigfoot: there are specimens in museums and one lived in a zoo. And yet: a peer-reviewed journal as recently as 2006 said there was no such thing as a kouprey.

Welcome to the story of one of the world’s great mystery mammals.

Meet the Kouprey

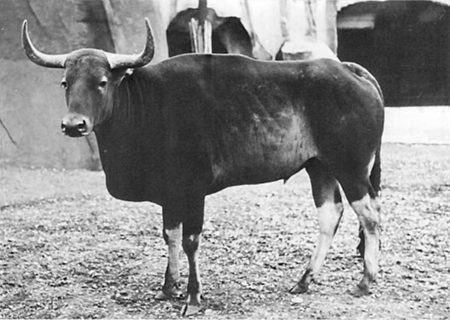

The kouprey is (or was) an impressive beast. The few who had the opportunity to observe the animal noted its tall appearance, in part due to very long legs. It had a humped back and curving horns. In males, the horn tips had a tendency to fray at the tips after a few years of age, giving them a peculiar appearance.

Perhaps the most notable physical feature was the large dewlap, a “sack” of skin that hung off the neck and could reach nearly to the ground.

Sources agree on this physical description. But beyond this, there is a lot of conflicting information, even among wildlife biologists and respected conservation sources. This animal has been shrouded in mystery for a very long time.

Let’s clear up one myth right away: the kouprey was not “discovered” in the 20th century, as many accounts claim. The kouprey, found in Southeast Asia, has been known by local residents for thousands of years. John H. Brandt, in his book Horned Giants, notes that 10,000-year-old cave paintings appear to be kouprey. The temples of Cambodia’s Angkor Wat also include carvings that look like kouprey.

By the 20th century, this wild bovine’s range was primarily in the forests of Cambodia, with some animals found in Thailand, Laos and Vietnam. While it was notoriously elusive, local people knew of its existence and had various common names for it, including koupro.

Foreign big game hunters hunted the animal in the 1930s, although what exactly it was remained a mystery. The Asian forest includes other bovines including gaur, banteng, water buffalo and domestic cattle. There is considerable variation in size and horn structure even within species. Was the kouprey a variation of one of these animals, a hybrid or an entirely new species? This is a question that would circle the kouprey for decades.

In 1937, the Vincennes Zoo in Paris received one of these mystery animals, sent by a colonial veterinarian stationed in Cambodia. This is often presented as the “discovery” of the kouprey, a bizarre claim given the evidence (but also fairly common for so-called scientific species discoveries). This was the first animal described by Western science. It would also be the only kouprey ever exhibited in a zoo. It died a few years later, during World War II.

Casualty of War

After that war, interest in the kouprey among hunters and scientists surged. Even then, the animals were not numerous, but most estimates suggest there were hundreds roaming around the forest. Brandt reports that Thai naturalist Dr. Boonsong Lekagul led one of the first post-war trips to search for kouprey, and he located (and shot) a couple of animals.

In the 1950s, explorer Charles Waterford led 90-person kouprey expeditions. While they failed at their stated goal of capturing any, they did observe and obtain the only video ever of the animal.

Around the same time, Cambodia’s Prince Sahounek declared the kouprey as Cambodia’s national animal. Even more significantly, he created kouprey refuges in an area where an estimated 400 to 500 animals still roamed. It was a promising development, but it would not last.

The war and conflict that would soon grip Southeast Asia took a heavy toll on the kouprey, likely lowering it to unsustainable population levels. With the many horrors of war, the toll it takes on wildlife is understandably overlooked. But around the globe, many large mammals have been endangered or eliminated by modern warfare.

The Cambodian war also left the forest littered with thousands and thousands of land mines. This not only posed additional threats to kouprey, it made further expeditions to the region extraordinarily dangerous.

Since that time, observations have drifted towards the realm of cryptozoology, where the sightings involve grainy footage or questionable circumstances. Many sources mention the species was last observed sometime in the 1980s. I have tried to find more documentation of these sightings, but have not been able to locate source material.

Some websites still optimistically state there could be 250 kouprey still alive in the wild. But most biologists have reached a similar conclusion: the species is most likely extinct.

And, for a time, some cast doubt that it ever existed.

Kouprey: Myth or Reality?

Of course, there were animals that were collected, hunted, photographed and observed. They were something different. But were they a separate species? This has actually been a question that scientists have asked throughout the 20th century.

What is a kouprey? Some said it was a separate species. Some believed it to be an ancestor of the domestic cow, similar or the same as the extinct aurochs of Europe. Others believed it to be hybrid of wild banteng and domestic cattle.

In 2006, a controversial paper claiming to look at genetic evidence concluded that the hybrid explanation was correct. For many naturalists, it was a logical conclusion. Many sources, such as Jose R. Castello’s Bovids of the World, note that kouprey were often observed in mixed herds with banteng and feral water buffalo. If you have a bunch of similar species mixing it up, you might expect hybrids.

And as stated previously, there is considerable variation in the horn sizes and shapes of cattle. So the idea that wild banteng and feral cattle bred (which happens), and resulted in the kouprey, made sense. It gathered a lot of media attention. Perhaps it absolved humanity of a little guilt. We didn’t eliminate the kouprey; it was basically just a cow after all.

A year later, another team of researchers did a much more thorough genetic analysis, including a kouprey skull found that dated before cattle domestication. This resulted in a peer-reviewed paper that demonstrated, definitively, that the kouprey was a real and naturally occurring animal.

But are any left? As the X-Files slogan goes: “I want to believe.” I do. I’d love to imagine this tall wild ox with frayed horns still out in some remote corner of the forest. But like the thylacine and the imperial woodpecker, I’m forced to accept these creatures now roam only through dreams.

This article is very interesting, but it is so sad that they are extinct. Reading about these extinct animals makes me sad.

So interesting – sad if they are truly extinct. I love reading about there-wilding being done in various European countries. And there there is the US – slaughtering our wild predators as fast and in as many horrific ways as possible.

What a comparison, right?

I’ve always been fascinated by rare and extinct wildlife but had no idea of the existence of the remarkable colour film of a herd of Kouprey from the 1950’s! Its wonderful!

Amazing footage.

This is a great article, thank you. It’s really good to shine the spotlight on these magnificent species that rarely get discussed or given attention. I’ve read about the kouprey before, along with other rare (some already vanished) and poorly studied bovids and find the theories behind their origins fascinating. I hope this is the start of another great series (like your freshwater fish series, which was excellent).

Thanks again!