Climate change is the defining crisis of our lives. (Well, that and the pandemic, but that too has roots in environmental destruction.)

It touches everything: the food we eat, the products we consume, where we live, how we commute, the critters in our backyard and the natural places we escape to try and stay sane. And so it makes sense that the climate crisis is now seeping into modern literature. Some novels are explicitly branded as climate-fiction, while in others environmental disasters merely eat away at the edges of the story.

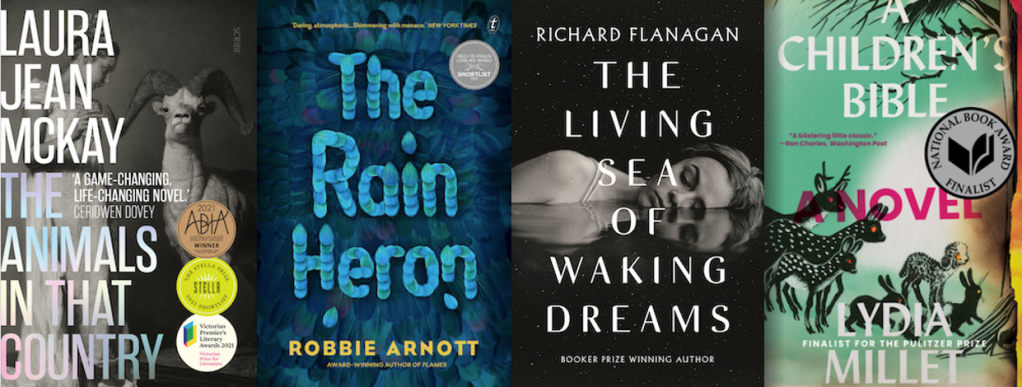

Last year, we brought you eight novels from authors who write passionately about the natural world. Now, here are another four fantastic works of fiction that take a long, hard look at the Anthropocene.

These writers weave eco-anxiety into their stories, but no two novels are the same: There are mythical creatures, disappearing body parts, children galavanting through post-apocalyptic wastelands, and a dangerous flu that enables people to communicate with animals.

-

The Rain Heron

By Robbie Arnott

It starts with a fable from a fictional land, of “a huge heron, the color of rain” who can make or break a farmer’s crop, who can summon storms on the wing, and vanish into thin air.

Years later, a military coup has plunged the country into war. Ren tries to escape the violence by living alone on a remote mountainside, haunted by loss. But soon a young soldier arrives, forcing Ren to help her find and capture a mythical creature living in the heart of the mountain: the rain heron.

Arnott’s novel reads like a multi-layered myth, but one reminiscent of our own time. The powerful seek to control nature, manipulating it for their own devices. Small communities living sustainably are torn apart by capitalist greed. Traditions are lost, wilderness destroyed. The story unfolds in a fictional country strongly reminiscent of Arnott’s native Tasmania; the landscape is just as much a part of the story as the characters.

Arnott didn’t intend to write a climate novel. But the catastrophic 2019 bushfires raged across Australia as he was writing his book, and over time his “pages began to crease under the weight of environmental chaos.”

(Readers should also check out Arnott’s first novel, Flames, which is also excellent.)

-

The Animals in That Country

By Laura Jean Mckay

What if we could understand what animals are thinking? As it turns out, that might not be such a great idea.

Jean works at a wildlife park somewhere in northern Australia, where in-between shifts she drinks herself into oblivion and cares for her beloved granddaughter, Kimberly. News begins to trickle in about a dangerous virus sweeping across the country, a flu whose main symptom is that its victims can understand the language of animals. First mammals, then birds and reptiles, then insects… until the cacophony makes them lose their minds.

The caretakers barricade themselves inside the park, but Kimberly’s deadbeat father arrives, kidnapping his daughter and infecting the staff. Jean, sick with the “zoo-flu,” takes off into the desert on a rescue mission with a wise-cracking dingo named Sue riding shotgun.

Two years ago this plot would be quirky, but in 2021 it feels all too real.

Laura Jean Mckay is a masterful storyteller, and once I started reading this novel I couldn’t put it down. Jean is both vile and entirely relatable. The inner monologues of the animals are by turns inventive, hilarious, and downright disturbing. The societal collapse, the petty dramas, and the unexpected plot twists will keep you hooked until the end. This is one of the best books I’ve read in years.

-

The Children’s Bible

By Lydia Millet

It’s summer vacation somewhere in coastal New England. A group of old friends rent a semi-dilapidated mansion for the summer, day-drinking themselves into a stupor as their children run wild over the estate.

But then a hurricane destroys the eastern seaboard. The kids, resentful of their parents’ hedonism and general uselessness, steal a few vehicles and take off into the storm’s aftermath in search of safety. They find refuge on an old farm, sleeping in the barn and eating rations from a survival bunker. Little Jack tries to make sense of it all by reading a new book he’s discovered — a Bible — interpreting the stories within as a metaphor for science.

The resulting story reads like the lovechild of Lord of the Flies and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, with a dash of Biblical symbolism. Short, sharp and clever, Millet’s novel examines what happens when the climate crisis creates a generational divide, between the parents who ignored it and the children who must survive in the aftermath.

-

The Living Sea of Waking Dreams

By Richard Flanagan

Francis is dying, if only her children will let her. As she lies in her hospital bed, entangled in the tubes and wires keeping her alive, Francis hallucinates a strange world outside her window, where one-eyed humans roam amid fires and floods.

Anna and her three siblings refuse to let their mother die, calling in all the resources available through their wealth and privilege to keep their mother alive just a little longer. As the months go on, Anna begins to notice that pieces of her go missing: first a finger, then a knee. But no one else seems to notice, even when they too start disappearing piece by piece.

Francis lurches from one medical disaster to the next, and the siblings bicker, and the climate crisis unravels the world. Anna hides in the bathroom stall, distracting herself with social media and cat videos as she wonders — and then ignores — what’s happening. The only thing that gives her hope is a chance encounter with a scientist trying to save the doomed orange-bellied parrot.

Flanagan is one of my favorite writers; his stories stick in my gut long after I’ve put the book back on the shelf. This latest work is a frightening exploration of what it means to be alive in a dying world, and of how we can nurture hope in the face of the inevitable.

I urge you to consider as well ” MEANDER: Making Room for Rivers” by Margaret Wooster (SUNY Press), a book with national implications about the need to change flood control policies. Drawing upon her own work on a western New York tributary, Buffalo Creek, Wooster demonstrates how dedicated people can recover what, through misguided policies like stream straightening, spoils dumping and the imposition of rickrack, we have nearly destroyed in our watersheds.