Brood X is finally here and every time I step out of my suburban Maryland home during daylight, I hear them singing. I’ve been looking forward to CicadaPalooza since January, and spent my pandemic winter reading up on all things magicicada. And there are a lot of things magicicada these days, which has been both fun and a little overwhelming.

Word of caution: If you’re looking for a formal cicada FAQ or primer, this is probably not that list. Well, not exactly. There are Cicada 101 type stories in here, but mostly this is me sharing a selection of my favorite stories, podcasts and sites from my (ongoing) foray down the Brood X cicada rabbit hole (or “cicada tunnel,” if you prefer).

Sometimes I was led to an article because I had a specific question, like, “What is the weird white powder I see on some cicadas?” (Answer: a fungus), or do cicadas taste like chicken? (Answer: Apparently not).

But mostly, this list is a mix of stories about cicada natural history, cicada misconceptions (I’m looking at you, copperheads), the challenges and threats cicadas (especially long-lived 13- and 17-year broods) face from loss of habitat, climate change and disease, and other pieces that caught my curiosity. (Hello, stories about dogs—and other animals—that can’t stop gorging on cicadas).

Even if you’re not in the part of the U.S. currently enjoying (or bemoaning) the 2021 Brood X emergence, there’s something here for everyone. After all, cicadas are known to live on every continent except Antarctica.

I’m always looking for more interesting pieces to add to my cicada (periodic and annual) content collection, please share your favorites and recommendations in the comments.

-

Meet Benjamin Banneker, the Black Scientist Who Documented Brood X Cicadas in the Late 1700s

Nora McGreevy, Smithsonian Magazine

A statue of Benjamin Bannecker on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC © Bart Heird/Flickr Born a free Black man near Baltimore in 1731, Benjamin Banneker was a polymath especially accomplished in mathematics, mechanics and astronomy. He is known for publishing remarkably accurate farming almanacs and serving on the team led by Andrew Ellicott that surveyed boundary lines for the city that would become Washington, D.C. That same year, 1791, Banneker also corresponded with Thomas Jefferson to explicitly and pointedly challenge the then U.S. Secretary of State’s comments that intelligence was correlated to race.

But until recently, he rarely got much (if any) credit for the value of his contributions to the science of periodic cicadas. He observed them as a young man in 1749, when he was about 17, and though he didn’t know it at the time, it was a kind of symmetry. He was roughly the same age as the 17-year Brood X cicadas he studied. (Like many people of that time, Banneker called them “locusts.”) He eventually predicted that the cicadas were on a 17-year life cycle, and may have been one of the first scientists to do so.

This Smithsonian article by Nora McGreevy led me to a trove of other interesting stories about Banneker, including a 2014 paper published in the Journal of Humanistic Mathematics that argues Banneker’s contribution to cicada science has been largely overlooked because of his race.

The paper is very accessible even if you, like me, have never heard the phrase “humanistic mathematics.” (Essentially, in the words of Mark Huber, one of the journal’s founding editors, humanistic mathematics is the study of the aesthetic, cultural, historical, literary, pedagogical, philosophical, psychological, and sociological aspects of mathematics as a human endeavor.)

The Maryland Center for History and Culture has a lot of information on Benjamin Banneker, including digitized pages from his journals and almanacs.

-

This Parasite Drugs Its Hosts With the Psychedelic Chemical in Shrooms

Ed Yong, The Atlantic

Pharaoh Cicada – Magicicada septendecim with fungus – Massospora cicadina, Carderock Park, Carderock, MD. May 24, 2021© Judy Gallagher/Flickr True confession: I read everything the Atlantic’s Ed Yong writes. If he wrote a book about the intricate science of paint drying, I’d probably give it a chance. He’s that good. Luckily for the cicada curious, he’s been writing about cicadas for some time, and this piece, from July 2018, is still my favorite.

I defy anyone interested in cicadas (or even natural history for that matter) to resist an article about a fungus infecting American cicadas that opens with this sentence: “Imagine emerging into the sun after 17 long years spent lying underground, only for your butt to fall off.” The article goes on to explain how the Massospora fungus infects cicadas and turns them into “flying salt shakers of death.” Spoiler alert: it involves a hallucinogen and an amphetamine, and then it gets weird.

Bonus Ed Yong article: Cicadas have an Existential Problem (May 2021), about the symbiotic bacteria that live with Brood X cicadas, in which I learned the word, “endosymbiont.” Read it for the fascination of the story and to appreciate that last sentence (that kicker is vintage Yong).

The video above showing cicadas infected with Massospora is from Mike Raupp’s Bug of the Week YouTube channel, which is discussed in more detail a little further down this list.

-

Brood X Cicadas are Emerging at Last

Kate Wong, Scientific American

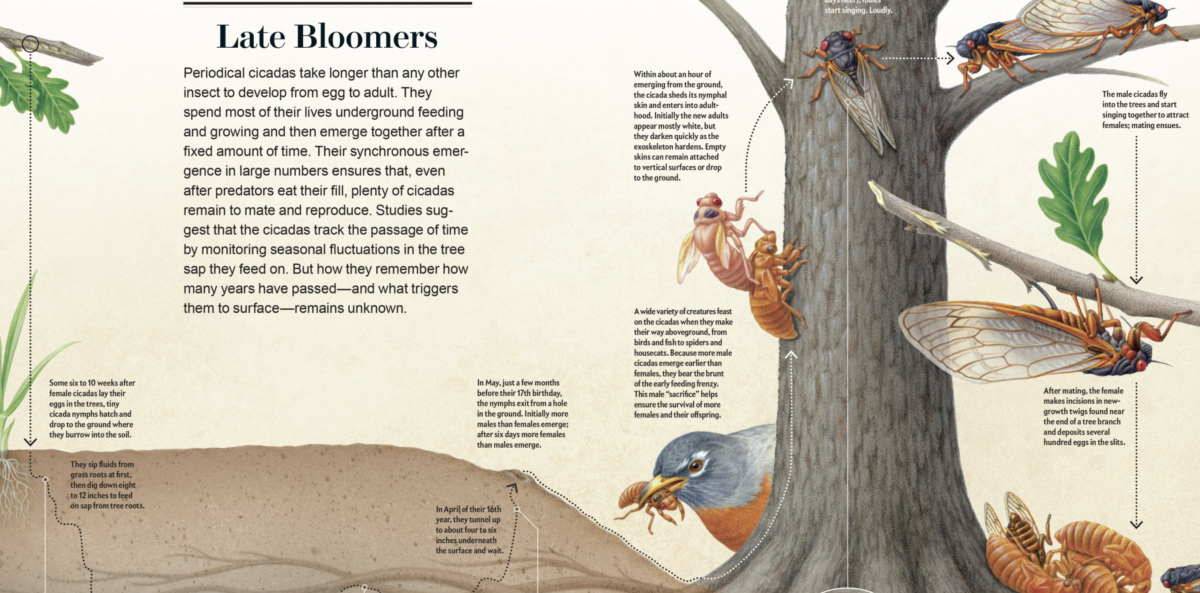

Explore Cherie Sinnen’s beautiful illustration of the life cycle of 17-year cicadas in Scientific American © Cherie Sinnen The best and most interesting narrative cicada primer-ish story I found is, unsurprisingly, from Scientific American. It’s by Kate Wong, and this is the story I send to people who want to understand cicadas, but don’t want to follow me down the full-on CicadaPalooza tunnel experience.

It’s a great overview and explanation of cicada natural history (no, they’re not sleeping underground for 17 years. They’re pretty active down there). It also has a very clear explanation of how brood descriptions and numbering works, the differences between periodic and annual cicadas, and why the 17-year cicadas of Brood X are special. The piece also includes a list of when and where each brood will appear, or, in some cases, where and when they’ve most recently emerged in previous years.

It touches on climate change, habitat loss and other challenges—and they are legion—to the survival of cicadas in the U.S. and around the world.

The piece is beautifully illustrated by Cherie Sinnen. The large annotated illustration of the Brood X cicada life cycle is really a triumph on its own and, if this the only thing you read about cicadas, you’ll get all the main points—and the Brood X madness specifically, and CicadaMania, in general, may make a lot more sense.

-

Billions of Cicadas Emerge After 17 Years

Deborah Landau, The Nature Conservancy

If you prefer to get your cicada information more visually, this video, narrated by TNC scientist Deborah Landau, is a quick listen, with a ton of great information and includes some cicada myth-busting as well. If you want to get even deeper into the what, why, when of the 2021 Brood X emergence, there’s a companion article and FAQ (also by Landau) that answers specific questions in a pithy, accessible format.

If you have science and natural history questions about cicadas, this story probably has you covered for all the basics. I love it because it does such a good job of answering the most common questions: Are cicadas poisonous to your pets? (no), or why are they so loud? (mating calls because they need to accomplish a lot in a short amount of time), or why are there so many of them? (ditto on the short amount of time to get everything done and also it’s a species survival strategy), or do cicadas bite or sting? (also no, though I can attest that their feet and legs can be a little prickly if one happens to land on your bare skin or in my case, in your ear).

I also really enjoyed this video showing cicadas emerging from their exoskeletons and featuring a discussion about how scientists are using the 2021 Brood X emergence to answer important questions about cicadas themselves and their effects on both forest food webs, and other species.

-

Cicada Crew

University of Maryland, Department of Entomology

If you’re looking for a one-stop periodic cicada informational site, this might well be it. Run by a team from the Department of Entomology at the University of Maryland (UMD), this is also the home of Mike Raupp, professor emeritus and Fellow of the Entomological Society of America.

If that name is familiar to you, you’ve probably been reading articles on cicadas. He’s a go-to source for journalists and also well known for his Bug of the Week site and YouTube channel of the same name. Really, if you haven’t spent any time with Dr. Raupp’s Bug of the Week, you are completely missing out.

The Cicada Crew site is extremely well-organized and easy to navigate. There’s a detailed FAQ on amazing periodic cicada facts (Question: will a cicada pee on me if I pick it up? Answer: Odds are good. Pro tip: If you’re in woods full of cicadas, wear a hat. Seriously. You’ll thank me.) The site also has fantastic gallery featuring pictures and video that are fascinating to click through and can help you learn to identify the three different Brood X species in the magicicada genus. There’s also a resource list so full of links and content, it will lure you down the cicada tunnel faster than Alice dove down that rabbit hole.

And, okay, since we’re here, let’s talk about periodic cicadas and copperheads. It seems to be a common belief that periodic cicada emergences automatically mean a population boom in copperheads, and an increase in copperhead bites to humans because there are more snakes than normal in the woods.

Ray Bosmans, Professor Emeritus at UMD and President of the Mid-Atlantic Turtle and Tortoise Society, has an article on the Cicada Crew site specifically addressing the cicada-copperhead misconception. The TL;DR version in a nutshell: “The emerging cicadas will not ‘attract’ more copperheads than already live in a given area,” writes Bosmans. “In other words, if you see copperheads feeding on cicada nymphs it means that copperheads have always been there and were not ‘drawn in’ from distant habitats.”

It is true that copperheads (and other animals) will gorge on cicadas if they’re available. After all, they’re a great source of protein, and don’t have defenses like stingers, teeth or toxins. They’re a good meal for minimal effort. And if you’re interested in some up close and personal footage of Kentucky copperheads dining on cicadas, there’s a Facebook site run by photographer Sarah Phillips featuring exactly that. The videos are mesmerizing, but probably not for people who are Nope to snakes.

For more on what is eating cicadas and how the abundance of food can affect their different life cycles, Meryl Kornfield has a piece in the Washington Post with some nice detail on rats, snakes, moles and the documented baby booms among birds during periodic cicada emergences. And of course, there’s the tale of Max the dachsund, who recently required an intervention to curb his out-of-control cicada addiction and save his human’s carpets and his sanity.

-

So You’re Thinking About Eating A Cicada: Tips From A Cicada Enthusiast

All Things Considered, National Public Radio

Brood X cicada in its teneral stage (just emerged from its exoskeleton, which can be seen still attached to the tree to its left.) Over time, the cicada will turn black and its body will harden. Apparently, cicadas in the teneral stage make the most tender eating. © TNC/Cara Byington To eat a cicada, or not to eat a cicada. It’s a dilemma that is apparently becoming fairly common and NPR’s Ari Shapiro and Mary Louise Kelly tackle it with their usual flare in an interview with anthropologist and “cicada enthusiast,” Dr. Cortni Borgerson, who has tips for those thinking of expanding their culinary and dietary, um, repertoire. She’s definitely pro cicada-on-the-menu and considers them, and I quote, “a really delightful small, meat item.” It gets better from there.

A search on “eating periodic cicadas” taught me a new word: entomophagy, which means insect-eating and also turned up any number of interesting stories about cicadas, how-to guides with tips on catching, cooking and snacking on cicadas, and, of course, cicada recipes. There’s a delightful (if slightly traumatizing) first-person account from the intrepid Haley Weiss describing her experience as an entomophagist (insect eater) for a day. Sadly, it did not exactly end well. The word “gusher” is involved. I don’t think that’s ever a good sign in a story about food, and that probably goes double when it’s a story about insects as food.

If you’re squeamish or otherwise on the fence about experimenting with eating cicadas, one expert says it might be helpful to think of them not as “bugs” or “insects,” but as “tree shrimp,” and (bonus) tree shrimp, like the better-known regular shrimp, are low fat and gluten-free. It’s best to harvest and cook tree shrimp in the nymph or teneral stage (when they’ve just emerged from their exoskeletons, but before their bodies harden and turn black).

Brood X periodic cicada struggling free of its exoskeleton. Once it has pushed itself out, it will enter the teneral stage. Anne Arundel County, Maryland. Brood X Cicadas, June 2021 © TNC/Cara Byington And depending on how they’re prepared some people think magicicada cicadas taste like pork, not chicken, and others with perhaps more, we’ll call them “refined” palates, liken the flavor of Brood X to roasted chick peas or nutty asparagus (which, honestly, sounds like a great name for a band). Apparently the wings can be a bit leathery and are best avoided. For her part, Ms. Weiss advises cicada-curious diners to stick with air fried.

A note re: “tree shrimp.” The name is not necessarily a misnomer. Cicadas, shellfish and crustaceans are in the same family (arthropods), so if you’re allergic to one family member, so to speak, you may be allergic to them all. Bottomline: if you know you have shellfish allergies, the Food and Drug Administration suggests you give those cicada tacos a hard pass.

Thank you for organizing this list, Cara – it was just the rabbit hole of curiosity that I didn’t know I needed! So fascinating.

Hi Kari — Thanks! and thanks so much for reading Cool Green Science. — Cara