The Nature Conservancy mourns the recent passing of Dr. Robert Jenkins, who served as the organization’s first science director. His approach not only shifted how the Conservancy worked, but also fundamentally changed the practice of land and water conservation.

For most of The Nature Conservancy’s current staff, trustees, members and partners, the organization’s science-based approach today almost goes without saying. The same is true for the Conservancy’s focus on biodiversity and prioritizing work that has the most lasting results for conservation. These are all important components of the Conservancy’s identity. But that wasn’t always the case.

While the Conservancy was founded by ecologists in 1954, by the 1960s the organization focused almost exclusively on land deals. The approach was opportunistic and focused on protecting any open space. Leaders at the time offered a variety of reasons for protection, including wildlife conservation, outdoor recreation and even historical preservation. Determining what land to conserve often came down to individual preferences, availability or cost.

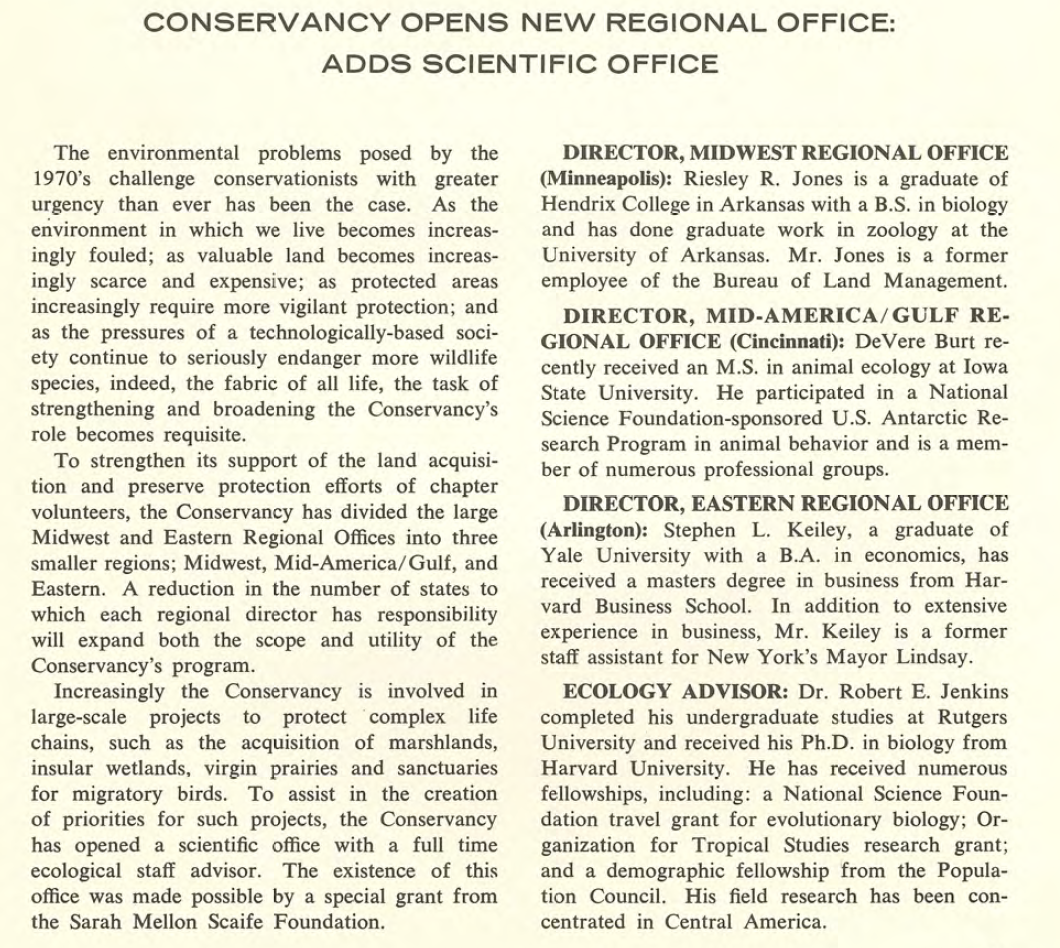

Bob Jenkins was hired as the first science lead for the Conservancy in 1970. It would be difficult to overstate his influence on how the organization has operated since. He argued successfully that the organization should focus on natural diversity. While that seems like an obvious conservation priority today, at the time the Conservancy became the first organization with a mission to protect biodiversity.

As Jenkins noted in a speech, he developed his idea to focus on biodiversity within the first couple months of his time with the Conservancy:

“At that point I rejected the ideas of saving prettiness, open space, and the like and decided that, in the abstract, there were two worthy objectives for natural land conservation. You could either seek to preserve ecological function, which I called carrying capacity, or you could try to preserve the full array of biological and ecological entities, which I called natural diversity. To have a meaningful impact on the first, I thought, would take an enormous effort, beyond the reach of a tiny conservation organization. Therefore, it seemed to me that TNC should seek to provide ecological lifeboats to save biological species and communities from extinction.”

Jenkins also recognized that to succeed in conserving biodiversity would require scientific evidence, evidence that at the time did not exist. You can’t conserve what you can’t measure, and data simply didn’t exist on the occurrences of species and ecological communities.

Jenkins led an effort with the Conservancy collaborating with South Carolina’s state wildlife agency in 1974 to inventory the state’s plant and animal species and ecological communities. Called the Natural Heritage Program, this model spread to every U.S. state and to nations in Latin America. The data collected by these programs were then used to identify the area’s most in need of protection

“In many ways, this program was the intellectual ancestor of what The Nature Conservancy is today,” says Michael Lipford, current Director of the Conservancy’s Southern US Division. Lipford formerly served as Executive Director of the Conservancy’s Virginia Chapter and was the first Director and Ecologist for the Virginia Natural Heritage Program, started by the Conservancy in 1986.

Jenkins developed and continually refined a data driven approach to prioritize and protect the rarest locations of plants and animals and the best examples of natural communities. He called this simply, “the last of the least and the best of the rest.”

The Natural Heritage Program was a key component of Conservancy science for nearly 20 years. As one journal article on conservation history put it, “The program generated extensive data on the status and distribution of rare species and ecological communities at the state and national level in the United States, as well as in Canada and much of Latin America. This data base remains widely used by TNC as well as by many government natural resource agencies.”

The data generated remain widely used by conservationists around North America.

In the 1990s, the network of Natural Heritage Programs, nurtured by TNC for decades, was established as a separate organization and became fully independent of TNC in 2000. It is now known as NatureServe. Jenkins served as science lead of the Conservancy until 1992.

As Jenkins himself noted, “You can’t imagine how little we had to go on in 1970—essentially nothing demonstrably reliable existed as to accuracy, currency, or even underlying intent.”

Colleagues and other conservationists knew him as a larger-than-life figure, a person of strong opinions and convictions. We remember his extraordinary conservation legacy and his continuing influence on the Conservancy’s science-based approach. We send our condolences to his family, friends and colleagues.

“He did so many things that we still benefit from today,” says Philip Tabas, Senior Advisor in the North America Region of the Conservancy. “The methods TNC uses to prioritize conservation have changed, but they have their roots in Jenkins’s approach. He demonstrated that to make the most difference, for people and nature, you need good data. That is still the case today.”

This is a wonderful tribute to Bob Jenkins. His vision and pioneering of what are now strongly accepted conservation objectives at TNC and beyond are great to read about.

The Jenkins approach is largely about “representation” – the fundamental principle that underpins modern conservation planning. What a wonderful intellectual legacy. Good science doesn’t age.

At times it seems odd the science team has to defend the principle against those who prioritise quantity (acres) over quality.