For years, the conventional wisdom was that Hawaiʻi’s land snails were largely gone, with little left to study, let alone conserve.

That wasn’t quite true. In fact, a research effort conducted over the past ten years has rediscovered dozens of Hawaiʻian land snail species previously thought extinct. And this summer, scientists described a new species, the first new, living species of Hawaiʻian land snail named in 60 years.

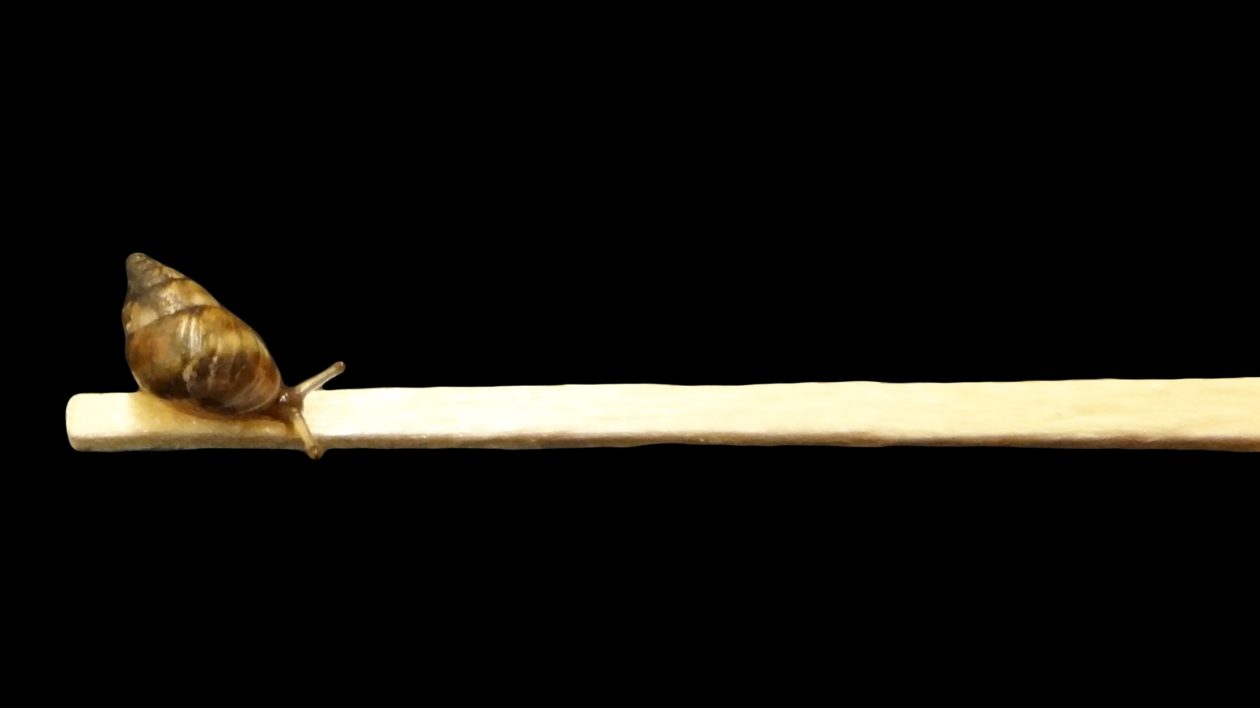

The species, named Auriculella gagneorum, is a small candy-striped snail from Oahu’s Waiʻanae Mountains.

A. gagneorum may be an unassuming little creature. But its story can shed light on just what we don’t know about the natural world – and why that’s important for conservation. As the title of the journal article describing the new species states, Hawaiʻi’s land snails are “overlooked but not forgotten.”

Snails Lost and Found

If you’re reading this blog, you probably know that elephants and giant pandas are imperiled. You might even understand the long-term declines of songbirds, or the concern about pollinators. But do you worry about mollusks?

Since 1500, 744 animal species extinctions have been recorded; 40 percent of those extinctions have been mollusks. And 99 percent of those lost mollusks are nonmarine species. Particularly hard hit have been Pacific Island land snails. In part because of their isolations, the land snails on Pacific islands have evolved in an astonishing variety of shapes, colors and habits.

They also evolved to fit specific ecological roles, largely without reptilian and mammalian predators.

Indigenous people knew and appreciated land snails; Indigenous Hawaiians saw them as significant omens of change. Habitat conversion by early western colonizers eliminated much of the low elevation snail habitat, and later invasive species posed an even greater threat. The snails were easy prey for species ranging from chameleons to pigs. And sometimes, other snails.

In the 1950s, in what is recognized now as a major biocontrol effort gone wrong, a carnivorous snail from Florida was intentionally introduced to control an invasive African snail. Instead of controlling African snails, the Florida snail had a voracious appetite for native snails, resulting in the decline of these unique species across the Pacific.

Climate change can exacerbate the native snails’ plight, both through loss of habitat and providing more favorable conditions for invasive species.

Hawaiʻi was once a snail diversity hotspot, with more than 750 species. But most malacologists had long ago written off most of these species, with estimates suggesting that only about 75 of these snail species remained.

“I was told to not even work on land snails in Hawai’i because there were none,” says Kenneth Hayes, director of the Pacific Center for Molecular Biodiversity and one of the co-authors of the recent study. “People talked about the snails in past tense, about how many species used to be here.”

This led Hayes to focus his research on invasive snails. But in the course of his field work, he kept finding native species. “Some of these species hadn’t been seen in years,” he says. “People were saying the snails were gone, but they hadn’t really looked.”

This led Hayes and colleagues, funded by a National Science Foundation grant, to begin searching for snails across Hawaiʻi. He was joined by Norine Yeung, malacology curator at the Bishop Museum, who studied seabirds for her Ph.D. before turning to the world of land snail conservation.

“People will ask why I would go from seabirds to snails,” says Yeung. “If you truly want to save biodiversity and keep ecosystems healthy, you need to study the little things. If you don’t conserve the invertebrates, it causes a cascade. And there is still so much we don’t know.”

Gone Snailing

Finding a tiny snail (many species are less than 2 millimeters long) in rugged terrain is not easy. In 2011, I spent a day with a native snail research expedition on the Pacific island of Pohnpei in Micronesia. We spent hours clambering through humid, steep forest. Then we spent hours on our knees, sifting through forest litter. I cam back from that day spent. The snail researchers had been at this for several weeks.

It’s a task that John Slapcinsky, another co-author of the study, knows well. Colleagues described Slapcinsky as a “master snailer” – which he says is “the best compliment I could receive.”

Slapcinsky traces his fascination with snails to a menu in a seafood restaurant that was decorated with marine snail images. “I thought they were beautiful creatures,” he says. “Years later I was mowing my lawn and saw land snails. I was curious and tried to find more information. It was really hard to find anything. I got hooked.”

Slapcinsky is now collection manager of invertebrate zoology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. And he’s never lost his enthusiasm for snails. “There is so little we know about invertebrates,” he says. “There is this unbridled ability to discover new things. It’s pretty much all out there to find.”

But finding is not easy. “Hawaiian terrain tends to be straight up and down,” Slapcinsky says. “You might be on a knife-edged ridge, on a cliff edge, clinging to a spindly tree. And then you have to sift through leaf litter.”

Surveyors investigated more than 1,000 sites across Hawai’i (including Nature Conservancy projects). They also relied on crowd-sourcing from various government agencies and other scientists. “We couldn’t search everywhere,” says Yeung. “We had others send us photos of snails they found. They often were really interesting species.”

While initial estimates guessed only 75 or so Hawaiian land snail species remained, the survey effort has located more than 300 snail species still around.

And some haven’t even been described by science. That was the case with Auriculella gagneorum. A U.S. Oahu Army Natural Resources Program survey, led by Vince Costello and Jamie Tanino, found an interesting snail and sent a photo. It looked similar to two known species but was well outside their range (genetic testing later revealed it wasn’t closely related to either).

Yeung and colleagues collected specimens and then set about comparing them to the extensive snail collection of the Bishop Museum.

“We couldn’t do this work without natural history museums,” says Yeung. “Many people think of museums as collections of objects and dead things. But the specimens in museums provide vital information for conservation today.”

When museum staff compared the collected snails to museum specimens, they found a match. It was a species collected 100 years ago and recognized as new to science at that time but never named.

“There can be a huge lag from discovery to description,” says Slapcinsky.

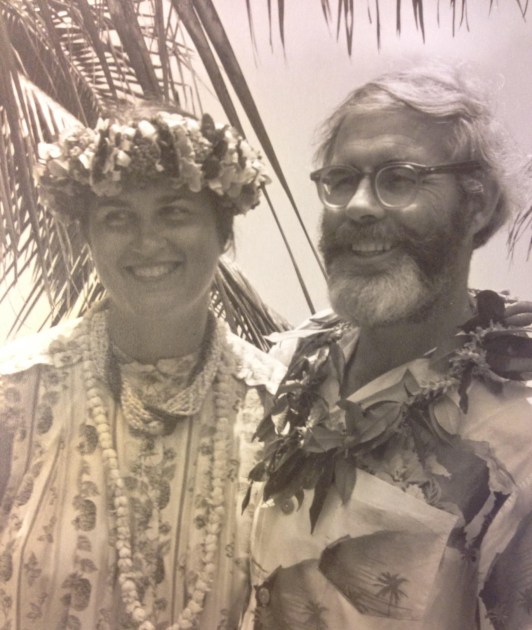

Slapcinsky and Yeung analyzed the snail’s anatomy, and Hayes sequenced DNA. When they confirmed it was a new species, they named it after conservationists Betsy and Wayne Gagne, both of whom valued all biodiversity, including snails.

Conserving the Creepy-Crawly Things

What does the rediscovery and naming of a snail species mean for conservation? With so many big issues, does this tiny, candy-striped snail even matter?

Hayes acknowledges what he calls a perception problem. “It’s not just with snails but invertebrates in general,” he says. “The creepy-crawly things rule most corners of the Earth. We talk about conserving biodiversity but invertebrates are large ignored by conservation.”

Species of snails and other invertebrates are going extinct before they’re even discovered. With that is lost all knowledge of their roles in the ecosystem and in providing ecological services. “I don’t want to keep reading papers about extinct species,” says Slapcinsky. “It is striking how little we know about our environment. We can’t effectively conserve biodiversity if we don’t know what’s out there.”

While there are more Hawaiian land snails surviving than many thought, they still face a precarious existence. Still, finding a “lost” species like A. gagneorum offers what Yeung calls “a glimmer of hope.”

In fact, the researchers delivered some of the snails to a captive breeding program, with a goal of increasing their numbers and returning them to the wild.

Yeung also sees hope in a growing appreciation for these snails, in no small part due to her education efforts aimed at everyone from grade schoolers to college students.

“If you ask a third grader about snails, they think they’re cool,” she says. “By high school, they’re gross. And most people walk by snails every day and never give it a thought. We don’t even know what roles these animals might play in their ecosystems. It is exciting what we can discover, but there’s urgency. We can’t save them if we don’t know them.”

Thanks so much, Matthew! Stephen J. Gould would be pleased. In addition to all his other talents, he was a snail guy, and his essay on the disappearance of island land snails in the Pacific, written for Natural History Magazine decades ago, brought me to tears. I’m glad to hear these little critters are hanging in there, even if I’ll never see them myself.