All conservationists have an origin story. A moment, a place, or an experience in our lives that laid down biophilia into our bones.

For many, it’s that archetypal neighborhood wood lot, a forest playground where we built forts, searched for salamanders, and watched fireflies in the dark summer nights. For others, it was summer fishing trips, a tattered field guide on the shelf, or a Ranger Rick magazine in the pediatrician’s waiting room.

For me, it was Steve Irwin.

Crikey, She’s a Beaut!

From ages 11 to 12 I was obsessed with Steve Irwin. I waited for the weekly episodes of The Crocodile Hunter with a religious zeal that (to my mother’s dismay) Sunday mass could never replicate.

I spent hours playing on the lakeshore in our backyard — dressed in khaki shorts and a wide-brimmed hat — using a net to catch minnows and tiny bass, crayfish and red-eared sliders. I’d narrate my exploits in an abysmal Aussie accent, pretending to star in my own television show for an audience of one.

Irwin mania gripped America just as I was entering the 6th grade, when the relatively innocent social hierarchies governing elementary school transitioned to the full-blown politics of early adolescence. As you might have already guessed, I was not a cool kid.

I’d always been a quiet nerd — my parents discovered that the most effective way to guarantee good behavior was to threaten to take my books away — and as I entered my early teenage years I remained firmly in the oddball group. My clothes weren’t stylish enough, my mother wouldn’t let me wear makeup yet, and I wasn’t willing to curry favor by letting the boys win at playground games of tag. The usual adolescent identity crisis ensued, aided by Mean Girls-level bullying and gaslighting from the popular girls.

But I had the outdoors. Away from school I could play as I liked, following raccoon prints across the sandy lakeshore and learning how to catch garter snakes with my mother. And I had Steve Irwin, who loved wildlife with an unabashed enthusiasm that a paralytically self-conscious tween girl could never muster. Irwin didn’t care if a snake peed on him or if he got dirty. He said weird things like “Crikey!” and didn’t care what other people thought of him.

If he could do it, then I could do it, too.

So I became the crocodile girl. I abandoned my dreams of being a veterinarian and decided to become a herpetologist instead. (This declaration was usually met with blank stares by adults and adolescents alike.) I had a crocodile birthday party, a dorky leather hat, and I even signed my name with a little crocodile stick hieroglyph of my own design.

While my love of crocodilians certainly didn’t make me cool, Irwin’s popularity gave me a shield. I was always going to be weird, but at least I wasn’t the only one.

Danger, Danger, Danger

My crocodile days faded with time. I changed schools, got a bit less awkward, and found a new identity in athletics and my love of language and literature. The crocodile girl became the volleyball player and wannabe poet, who later became a rower and lover of southern American literature. I forgot all about Steve Irwin, until I saw his obituary on the news during my first week of college. And then I promptly forgot about him again, until I started working in conservation.

Years after his death, Irwin’s reputation in conservation circles is mixed. Most criticisms of Irwin arise from his handling of wildlife, with detractors arguing that he unnecessarily harassed wild animals to benefit his own celebrity. Another often-mentioned incident occurred when Irwin walked through a captive crocodile enclosure with a dead chicken in one hand and his 1-month-old son in the other.

Despite the cowboy persona, Irwin was a serious conservationist. He helped found a research project with scientists at the University of Queensland, who still use his croc-capture techniques more than a decade later to tag and release dozens of saltwater crocodiles. The satellite-tracking data they gather is helping scientists better understand a creature that — for obvious reasons — would otherwise remain enigmatic.

I still have a memento from my crocodile days that my mother saved along with my crayon drawings of Florida panthers and manatees. It’s a small booklet marking our 6th-grade graduation, where each student wrote down what they want to be when they grow up. In my entry, I wrote that I wanted to be a veterinarian or a herpetologist, and that I wanted to move to Australia.

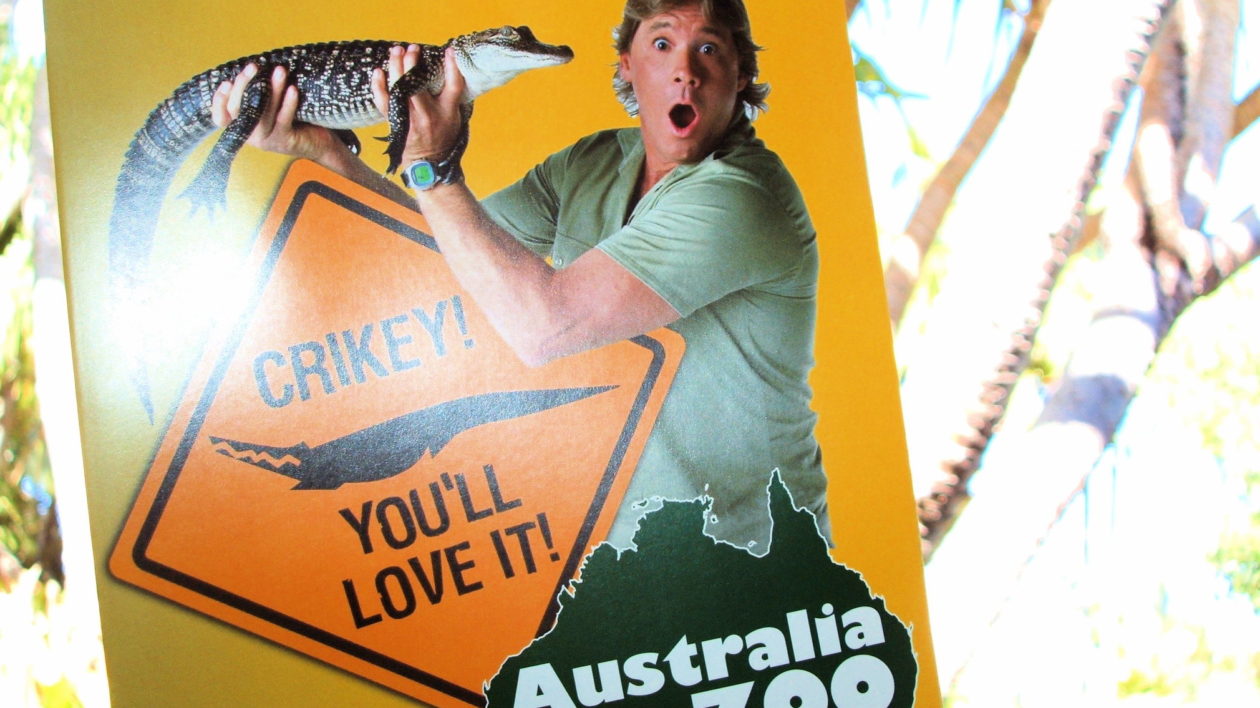

It was a wildly adventurous declaration for a child too shy to ask a restaurant maître d’ for directions to the bathroom. Yet it proved prescient. I’m writing this from my home in Australia, just 30 minutes down the road from Steve Irwin’s zoo.

In hindsight, I feel the same way about Irwin that I do about zoos. It will always hurt to see wild species in captivity, and yet zoos fulfill an essential conservation function. They safeguard species in need of protection, providing an essential reservoir of genetic diversity and scientific knowledge that we have relied on time and again to help save endangered species. And, equally essential, they connect people with nature they would otherwise never know.

Irwin is the same. I don’t advocate unnecessary manhandling of wildlife or toting bite-sized toddlers around large reptiles. But your average fisherman terrorizes more animals than Irwin, and no one is clutching their pearls over Grandpa’s fishing trip.

Irwin taught millions of children like me that wildlife — even the ugly, slimy, and scaly — should be loved. Before him, popular culture dictated that snakes and spiders and the other uncharismatic critters should be feared and eradicated. He taught me to love alligators, and myself. And he inspired and encouraged an entire generation of budding naturalists, scientists, and conservationists.

Did Irwin unnecessarily manhandle animals in the process? Probably. Is the Australia Zoo enterprise a bit too commercialized, with a patina of camera-ready schtick? Absolutely. I can live with both of those things.

I finally visited Irwin’s Australia Zoo about a year ago, with my partner’s 6-year-old niece and 8-year-old nephew in tow. We watched saltwater crocs lolling lazily in the Australian winter sun, ogled a cassowary scarfing down mangoes, and played “Where is the snake hiding?” in the reptile enclosure. I loved it. And I saw a ghost of my young self as I watched the kids run from one exhibit to another.

Some conservationists may raise an eyebrow at the mention of his name, but I will be forever grateful to Irwin for encouraging an insecure little girl to embrace nature with enthusiasm, curiosity, and compassion.

You are always a delight to read. My friend and I look forward to your blogs. I applaud your life traveled and that you ended up doing what and living where you wanted. Congratulations on a life path well done. I didn’t watch Steve Irwin–I am MUCH older than you– and he annoyed me in so many ways. I share your love of wildlife, your conservation ethic, and your love of Australia. (I vacationed there three weeks many years ago and fell in love with it.) Keep up the good work.

Love how you shine a light on both sides of the discussion about zoos and nature shows such as Steve Irwin’s. From one nerdy nature lover to another, nice job! It’s such fun following your adventures from afar!

nice story and interesting how this early “obsession” is reflected your present life. I enjoy your pieces on Asian Pacific natural world – thanks!

Well done Justine that was wonderful and very interesting to see that we can all follow our dreams and help our fellow animals and feel good about it.

Thoroughly enjoyed this article! Thanks for painting Steve in such a fair yet warm light. He was my childhood hero too, and I find that I still learn from him to this day–not just about conservation, but also about life itself.

My daughters were similarly inspired by Steve Irwin and were mesmerized by his fearlessness and enthusiasm. I think if he were alive today, he would heartily admit his mistakes and use them as teachable moments for conservation. I applaud the work he did and the legacy he left behind, both in his children and with his zoo.

Lovely article and tribute! Also enjoyed the article about weird Australian wildlife. Who would ever have thought…………….