My 5-year-old son burst through the front door. He excitedly told me he had just seen a “green snake” that had “kind of freaked him out.” Then he reached on the shelf for a reptile field guide. As he opened the well-worn book, I saw the inscription inside the front cover: a note from my grandparents for my 10th birthday.

We’re a field guide family.

Field guides have been a part of my life since I was a small child. The crisp illustrations of these guides have helped me identify countless species, from birds to chipmunks to snakes. But they’ve also served as invitations to adventures, as memories of days afield, even as a source of solace when I can’t be outside.

Naturalist Ken Keffer, in his recent book Earth Almanac, writes “You don’t have to be able to identify anything in nature to enjoy it. Just being outside in the fresh air can be relaxing.”

This is certainly true. Many of my friends, hard-core outdoor enthusiasts and conservationists, have little interest in identifying warblers or dragonflies. They live for scenic vistas or seeing the big and unmistakable critters like wolves or elk. They enjoy challenging themselves in the wilderness. They might photograph a patch of wildflowers but scarcely give the species names of those flowers a second thought. There’s nothing wrong with any of that.

But for me and many others (including you?), identifying plants, animals and natural phenomena is a big part of our outdoor enjoyment. As such, field guides are an essential component of our day pack and library. And how modern field guides originated is an interesting story in itself.

A Bird in the Hand

Naming and classifying our world is a universal preoccupation of our species. In fact, the earliest myths across cultures often detail how things got their names. There are practical reasons for this, but our obsession with naming and listing also became the basis for popular nature hobbies.

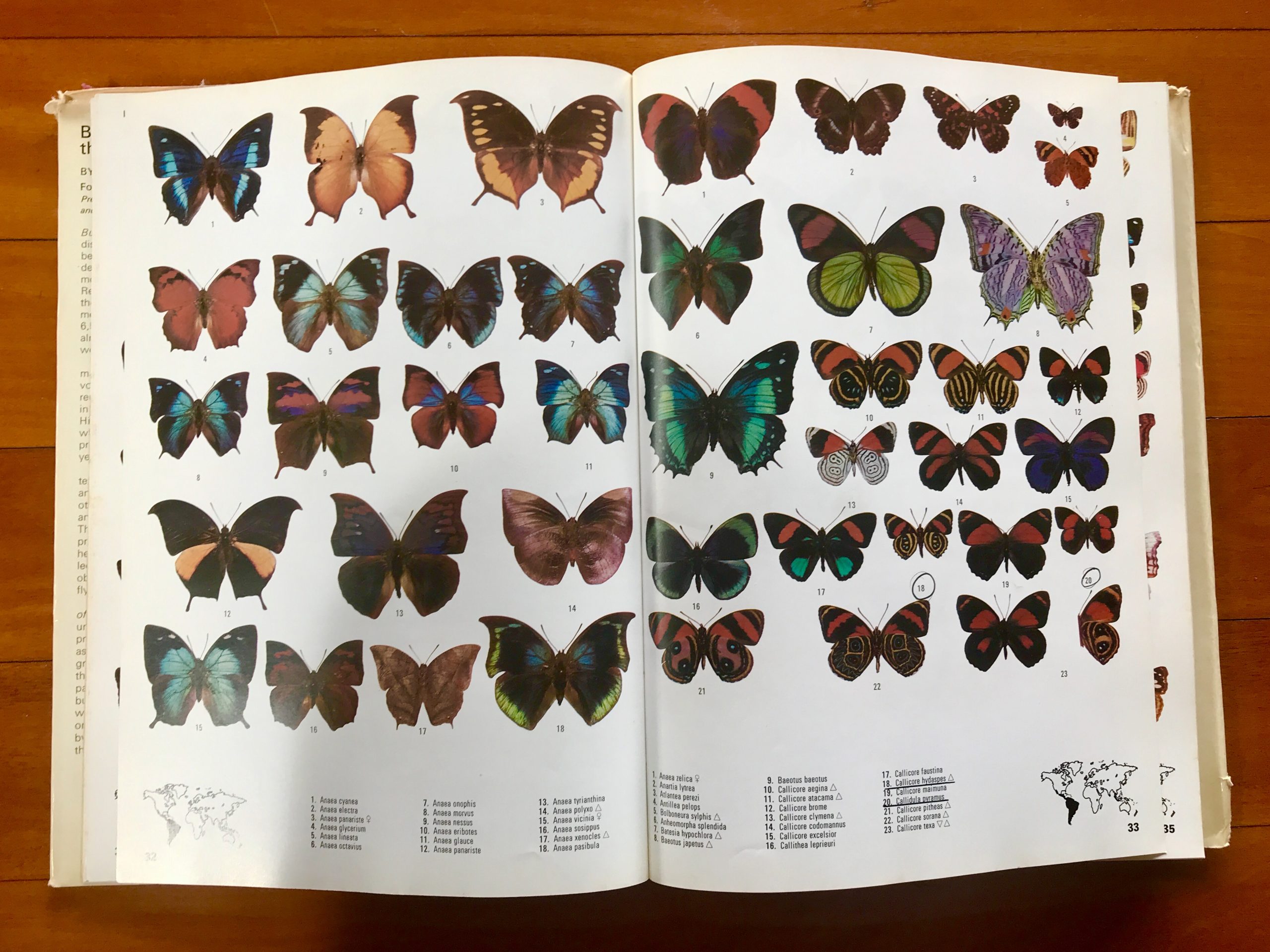

In Victorian Europe, for instance, collecting natural objects was an obsession across economic classes. Enthusiasts collected and displayed butterflies, bird eggs, fossils and more. Identification, if not simple, was fairly straightforward as the specimen was right in front of you.

For a long time, a key tool in bird identification was the shotgun. A bird in the hand could be readily identified. (Or painted. John James Audubon and others often shot birds before beginning their artwork).

As wildlife populations plummeted, collecting birds and bird eggs became unsustainable and socially unacceptable hobbies. In the United States at the turn of the 20th century, attention turned to conservation and new regulations protected many bird species. At the same time, bird clubs like the Audubon Society began popping around the country.

More people realized that you didn’t need a firearm to appreciate birds. Unfortunately, identifying species in the field remained tricky. There were guides, but many of these were detailed scientific keys, requiring a level of taxonomic knowledge that most amateur naturalists didn’t possess. Plus, these books were weighty tomes, impractical to lug around on a hike.

The Game Changer

Enter Roger Tory Peterson, a young artist who also happened to be obsessed by birds. In 1933, Peterson convinced Houghton Mifflin to publish a Field Guide to the Birds as a new way to identify our feathered friends. Rather than a detailed text key, Peterson used clear, crisp illustrations.

Those illustrations emphasized distinguishing characteristics of bird species, with small arrows indicating key identification points. As Peterson noted, “My identification system is visual rather than phylogenetic; it uses shape, pattern, and field marks in a comparative way.”

The guide featured very concise text, and could be easily carried in the field, or placed by a window for identifying backyard birds.

Houghton Mifflin had modest hopes for the new title, publishing 2,000 copies in its first print run. It famously sold out in the first week. It has not been out of print since then, and has sold more than 7 million copies, one of the bestselling nature books of all time.

As the Roger Tory Peterson Institute notes, “From 1934 on, thanks to Roger’s genius for simplification and communication, any amateur could learn to distinguish one bird from another. Birdwatching soon became a hobby—even a sport—for vast numbers of people.”

Instead of collecting bird specimens, as naturalists once did, people could now collect sightings.

That initial Peterson guide spawned a multitude of other field guides, not just for birds but for almost any other creature we might encounter afield. The Peterson Field Guide series alone now includes 52 titles. David Sibley’s guide, which added new ways to distinguish birds, was published in 2000 and became a New York Times bestseller. Several university presses, including Princeton University Press and John Hopkins University Press, now produce excellent fields guides on a variety of specialized topics.

Field guides have become as indispensable to naturalists as binoculars.

Start of an Obsession

As a child, dreams of exotic beasts filled my dreams, fueled by picture books and shows like Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom (I realize I’m dating myself). I wanted to walk among the elephants and jaguars and polar bears.

The Golden Guides, the first field guides I owned, were for me not for identification, but an invitation to adventure. With these guides, I realized that I did not have to wait for a safari to explore. There was plenty of excitement in the vacant field behind my home.

Favorites like Pond Life included most of the creatures I could encounter at the local creek, and also featured information on techniques like dip-netting, and suggestions for do-it-yourself “field research” projects.

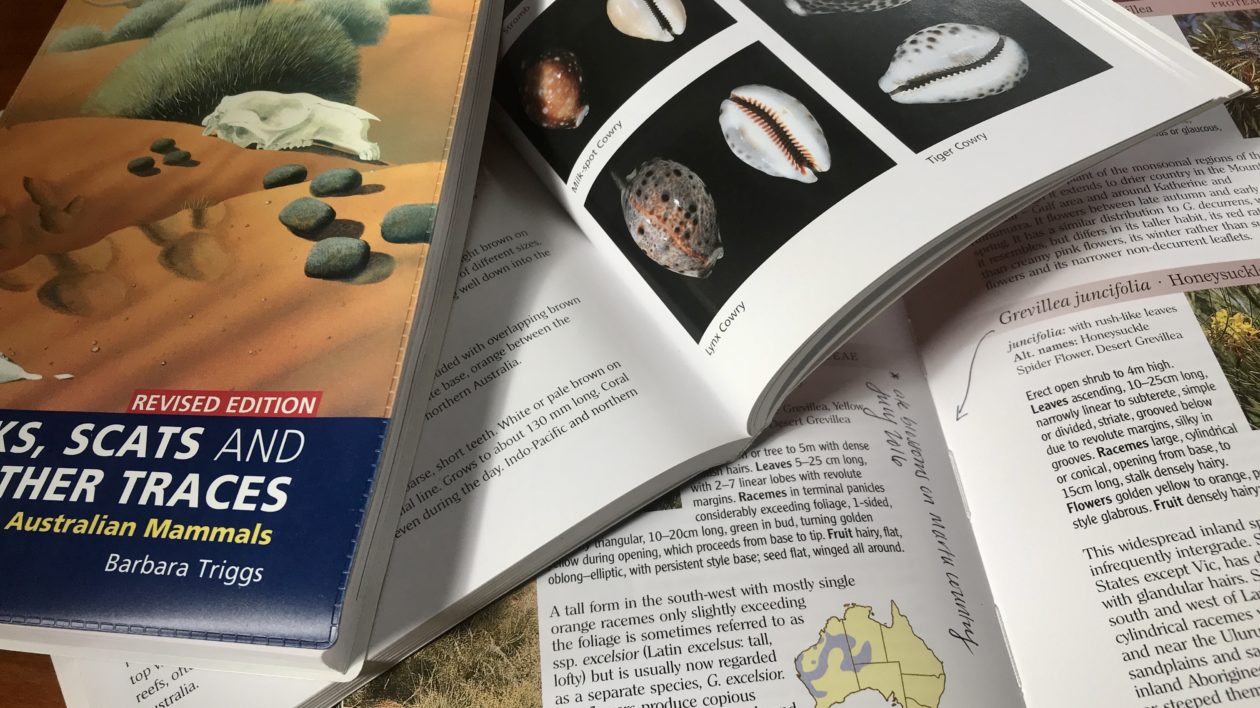

The Peterson Field Guide to Animal Tracks opened my eyes to another aspect to the natural world. The wild animals I didn’t see still left signs of their passing. A fresh snow revealed numerous critters that passed during the night. I tracked red foxes through woodlands, and stoped to identify mystery scat left by the streamside.

Field guides continue to add new dimensions to my outdoor pursuits. For many years, I was a pretty standard-issue trout angler. I might pause to identify a bird fluttering over the stream, but I didn’t think about identifying all the fish. Sure, I valued freshwater biodiversity, but I am embarrassed to admit I didn’t know much about it.

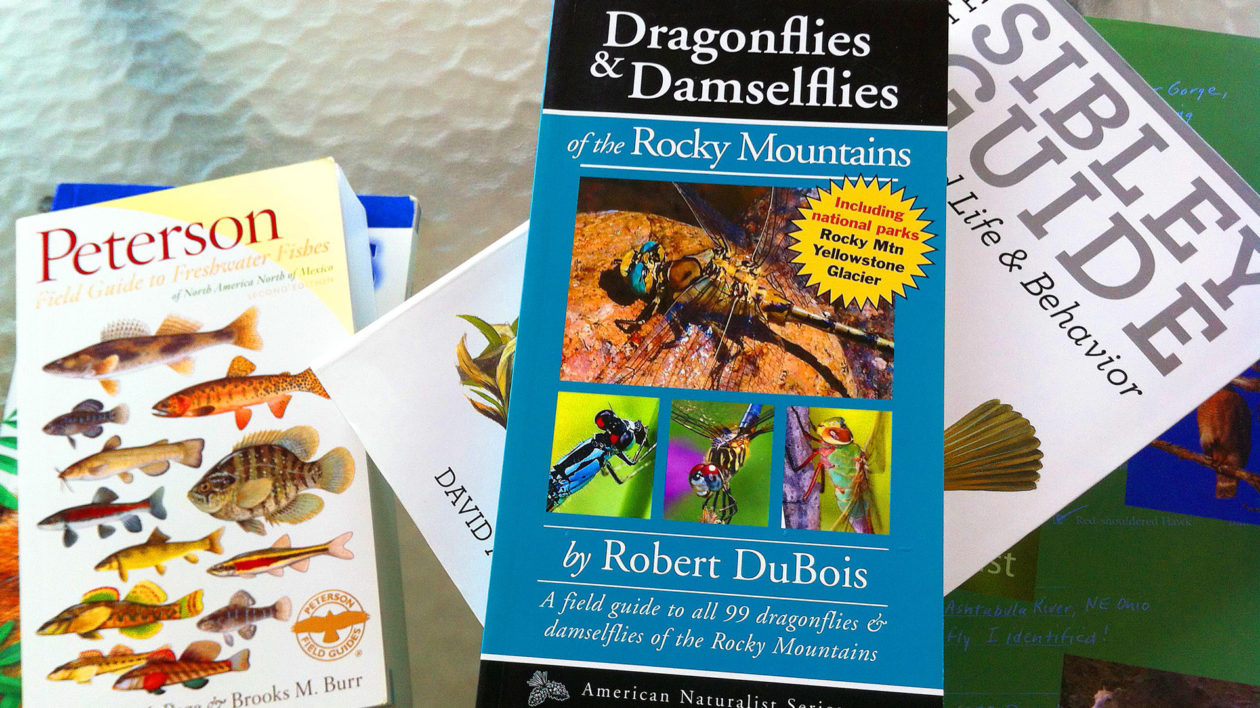

That changed when I received the Peterson Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes, a book that revealed I had shortchanged my fishing by overlooking so many species. I began to seek out new species wherever I went. Today, if I’m on a fishing trip, you can bet a field guide is in my tackle bag.

Today, my bookshelves bulge with field guides. I have them for big international trips I’ve done, and I have guides covering places I’d like to someday visit. I have field guides for Western squirrels, for Wisconsin stream life, for the frogs of Costa Rica and for non-native hoofed mammals of Texas. The variety is astonishing…and great new field guides continue to be produced.

The Fun and Solace of Field Guides

No, you certainly don’t need a field guide to enjoy the outdoors. But I guarantee that learning to identify the creatures around you will add new enjoyment, whether you enjoy wilderness hiking, hunting, cross-country skiing or backyard gardening.

With so many field guides, how do you choose? You might have specific kinds of wildlife that is just inherently more interesting. Perhaps you want to know more about dragonflies or fungi. I love mammals and fish, but I’ll reluctantly suggest this: Start with birds.

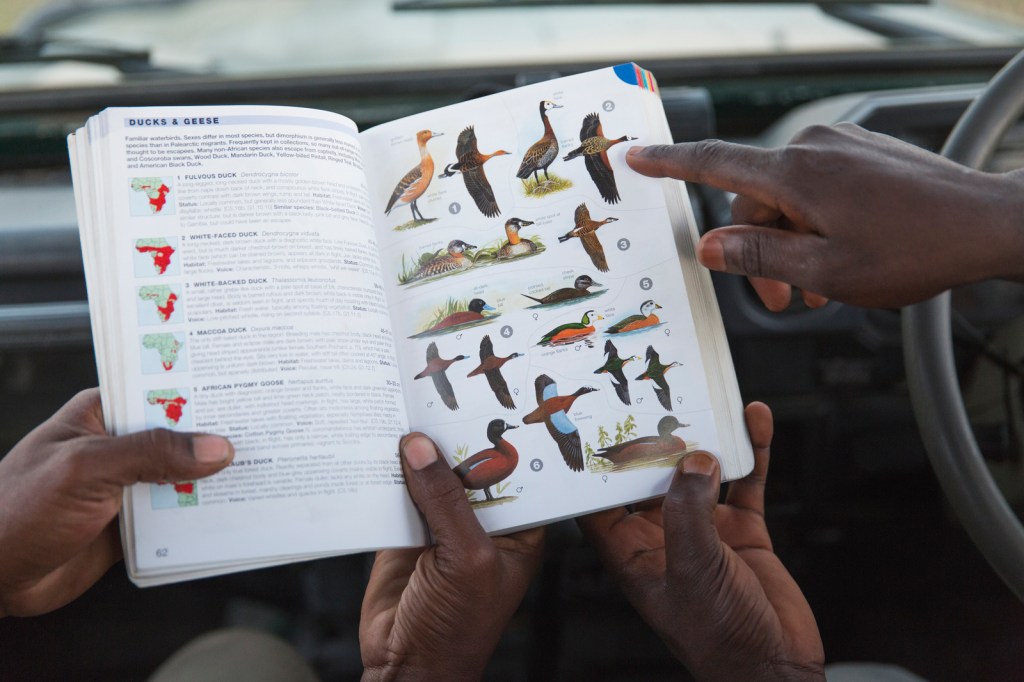

There’s a reason why Peterson’s first field guide focused on birds, and that bestselling new field guides center on the avian world. Birds are highly visible and abundant. A good field guide won’t solve every identification challenge, but you’ll figure out most of the birds you see at your feeder or on a hiking trip.

A lot of birds are diurnal. They can be colorful. They are often loud. While warblers or gulls may be frustrating, it’s nothing compared to identifying a bat on the wing or minnows in the water. Start with birds, but don’t be surprised if your first field guide leads to more.

Start with birds, but don’t be surprised if your first field guide leads to more.

Identifying nature is fun, but what I love most about field guides is that they change the way you see. As you develop field skills, some ducks will take off in low light and you’ll know they’re gadwalls. Not mallard, not widgeons. Gadwalls. You’ll know this because your eyes automatically pick up the cues you learned in that field guide.

The meadow you once just walked through will suddenly become a dramatic spectacle. Alive. You will stop and silently catalogue the creatures you know from previous sightings: Columbia ground squirrel, long-billed curlew, Cooper’s hawk. But what is that butterfly? Is that a swallow or a swift? Back to the field guides.

Of course, the latest revolution in field guides are apps and online resources. Now you can report your sighting, and have experts verify your ID. And what was once simply a hand-written “tick” in your book is now a data point for citizen science efforts.

Still, I love a field guide in my hands, and the page after page of nature illustrations. During this time of quarantine, I admit that thumbing through my collection is therapeutic. I find myself reliving past trips, and also dreaming up new trips and what species I might expect to find.

And when a snake appears on the trail, I’m happy that my son rushes back to look it up. That he wants to name the creature that crosses the path – a habit I hope leads to a life of nature exploration and enjoyment.

Absolutely agree with you. Field Guides encompass and combine, on my opinion, nature, knowledge, art and a fine sense on belonging in this wonderful world. And having them on and in hand it is more reliable than in an app. I hope and wonder next generations will apreciatte. Kind regards.

I have a bird life list and out of that has developed a field guide collecting habit (very surreptitiously I might add) I really can’t tell you how many I have at the moment but I am sure the collection is in the hundreds now, these guides cover everything that I find interesting Birds, Reptiles & Amphibians, Mammals, Trees, Flowers, Insects, especially Butterflies, Cactus, Seashells and they span 6 of the 7 continents. One comment I would like to make is in regards to the Golden guide to the Birds of north America – By Robbins, Brunn & Zimm and illustrated by Arthur Singer this guide as far as I know was the first to appear in the modern format of illustrations on one page and descriptive text and range maps opposite them, I remember trying to use the Peterson book that I had at the same time (1966) and finding that it was a major pain in the ass to use with some black and white illustrations, the range maps at the back of the book and the text in a third location once I had the Golden guide I never really looked at the Peterson. I still have it though. In my opinion the Golden Guide was the first “Modern” field guide released at least that I am aware of. I think I am going to go count my field guides now, well that is what stay at home requirements are good for. I found your article both informative and interesting.

I used field guides before Peterson’s were widespread. These were two by Chester Reed- one on birds, the other on wildflowers. The bird guide was first published in 1906! It was a gift to me from my grandparents for Christmas 1940. The pictures were quite poor but enabled me to identify many backyard birds in Virginia and cemented my interest in becoming an ornithologist (by the way I did become one of Cornell’s first female PhDs in that subject). All to the power of a field guide given to me when I was 7.

This was such a soothing article. My 5 year old son has been enthralled with his Birds of Central Florida and Saltwater Fish of FL field guides. His joy takes me back to 1993, I was 10, when a family friend bought me a shell field guide, while on a beach vacation in Montawk, NY. I collected shells, researched what they were, and put them back. There was no other place that I wanted to be. Sweet memories.

I was asked to identify two birds from a photo taken by friends. Out came my field guides. My friends were speechless, “But aren’t you a biologist?” they gasped. I nodded and went back to identifying the birds. I guess I am supposed to have an encyclopedic knowledge of all living critters but I learned long ago good references make for good identification. One bird they were sure was a cardinal wasn’t, it was a rare red phase of Western Blue jay, an unusual occurrance. The field guide gave illustrations and facts about itand they were amazed at the accuracy “that little illustrated book” had. The second bird was not a large hummingbird that they thought they had spotted ,but a ruby crowned kinglet. Impressed by my “little books” they asked when did I get them , my answer shocked them, 1975. I too value field guides, rarely travel without them and take 60 minute vacations when I need to go out and enjoy the wildlife around me, my “little books” in tow.

Wonderful write up on field guides. One of my collections as well. I lost my Zim Golden Guide for Birds. I loved the illustrations and especially it was the only one at the time that fit into my back pocket. then along came the hot National Geographic bird guide in the 80s and my Golden got lost. it seems to be out of print now. My loss. Thanks for your write-up.

Depending on which Golden guide you want to replace you are almost guaranteed to find it on Amazon I have had great luck finding old out of print books there.

Thanks, Matthew, for another great blog! My field guides go back to college, which means my Birds of North America is sort of out of date, considering how territories have been changing over the past, uh, 55 years or so. My favorites are Sibley Birds West; that one lives on the couch in front of the big south windows in case something fabulous comes along, and Robert DeWitt Ivey’s Flowering Plants of New Mexico. That one is a tome of clear, detailed ink drawings, all done from life all over the state, Dr. Ivey’s life work. No colors, and no detailed descriptions, but I can almost always find a plant with not much trouble.

The Golden Guide to Pond Life is still a remarkable little guide, I remember it from decades ago and used it as a resource guide in a Wetlands Education kit I developed for teachers at a previous job. I’m glad you mentioned it, that made me smile!!!

My dad and I used to bond over field guides. We’d take a bunch of little ones on road trips, take the binoculars, and camp at various state/provincial and national parks along our great looping route. Even now with the internet to help with identification when I’m home and not travelling much, I love to look at the old guides. They have great illustrations and inspire me to draw and paint more.

A man after my own heart – I have loved and enjoyed field guides for 70+ year! In England, my parents, who were not “naturalists”, but enjoyed nature, had several “Observers Guide to …” books, which I pored over. Then to Australia where keys to the flowers of Western Australia filled my high-school days.

Finally to USA, where Peterson’s Bird guide was the first of dozens of field guides, along the way to my Ph. D. in Biology, and teaching, which I still do today.

Thank you for a very nostalgic trip through life and nature.

I have lots of guides. I like to look at them even when I’m not outside. In fact, I almost never carry any around….but reading through them helps you notice more when you’re outside…..and see creatures, plants, birds, etc., that you will never see in person.

I have dozens of field guides. Have enjoyed them immensely over the years. Flowers mushrooms ants spiders lizards snakes. Favorite is stokes book of birds. Cost thirty dollars years ago. It has six hundred pages of delightful pictures and information. Along with it came a cd on the back of the book. It contains the identifying sounds of hundreds of birds. Now that I am elderly and can’t travel much I delight at the variety of birds that come to my feeders.

Thanks for the wonderful write up on field guides! I am currently working on expanding my collection of petersons right now!