I’m staring out the window again, seeking a burst of inspiration. The words are just not flowing. But fortunately, in my job, I can always look for story ideas in nature.

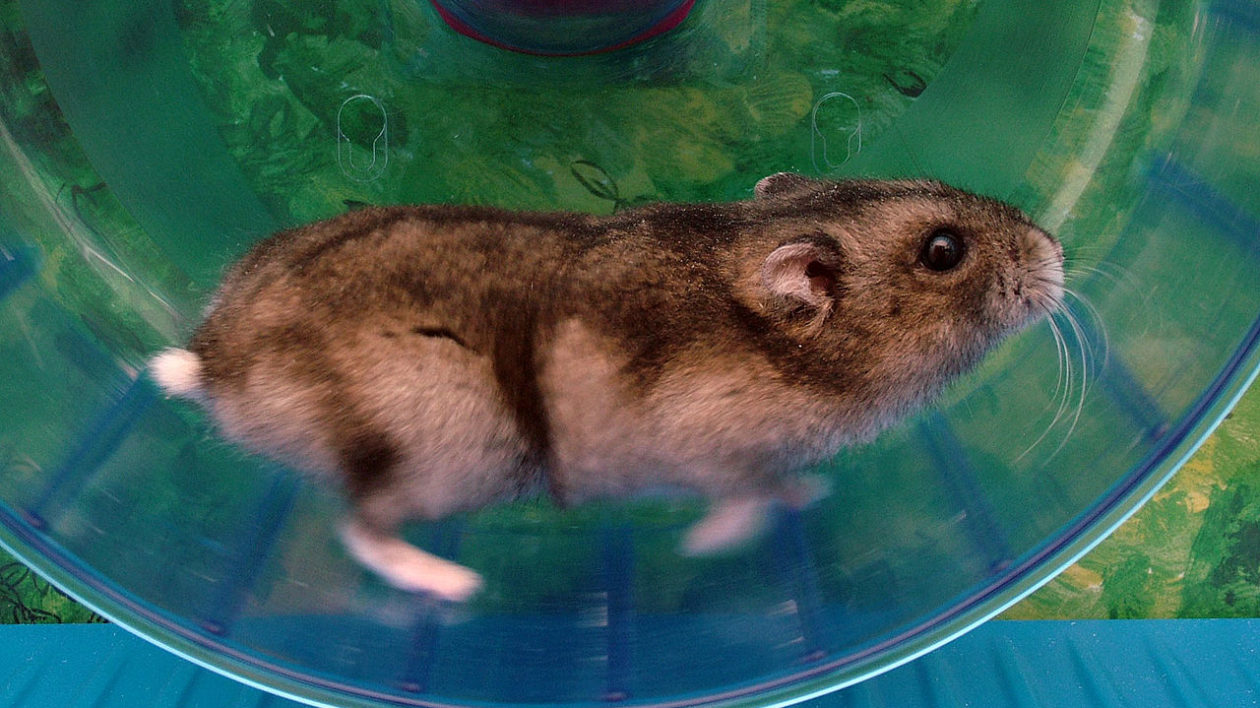

And then, behind me, a sound like thunkety-thunkety-thunk turns my gaze. It’s my son’s new winter white dwarf hamster, named Diggy. While Diggy is most active at night, she often arises around mid-day for a bout of running on her wheel.

As I watch this cute little critter, I start to wonder. A curious naturalist rarely has to look far for interesting questions. How did this rodent come to be a popular pet? Why does Diggy run around the wheel like that? What are her wild ancestors like, and how are they faring?

Let’s take a look at the fascinating story of hamsters in the wild, the plight of our pets’ wild cousins and, yes, why hamsters run on wheels.

The Quest for the Golden Hamster

There are 18 species of wild hamsters (maybe more, depending on the taxonomist you ask). All species are nocturnal, hoard food and live in burrows. Some live relatively solitary lives and some are social. They all look pretty cute, but many are actually quite aggressive and ill-suited as pets.

The hamster that got the pet craze going, the Syrian hamster, is actually one of the rarest. While there are some inconsistencies in the various accounts of the pet hamster’s backstory, the main expedition is well documented.

The Syrian hamster had been collected by explorers a couple of times, but remained a poorly understood animal. It was known as a rodent with soft, golden fur. In 1930, biologist Israel Aharoni decided to launch an expedition near the ancient city of Aleppo to find this almost-mythical creature.

Aharoni is an interesting figure in his own right. As Rob Dunn writes in a great story in Smithsonian Magazine, one of Aharoni’s main projects was matching animal descriptions in the Torah to existing creatures. He had heard the stories of the “golden hamster,” an animal whose Arabic name translates to “Mr. Saddlebags” for its roomy cheek pouches.

By most accounts, Aharoni did not enjoy travel or adventure. Anyone who has spent much time on research trips knows there can occasionally be someone who constantly complains about the food and lodging, sulks every morning and fights with fellow travelers. Aharoni was that guy. And he was leading a difficult trip to find a creature that may or may not still exist in the wild. It does not sound like a roaring good time.

But Aharoni persisted, in part to find another creature from the Torah and in part to find a better hamster species for medical research (the Chinese hamster was used in laboratories, but it wouldn’t breed, so new animals had to be constantly collected from the wild).

Aided by a local hunter, the expedition finally located a litter of wild Syrian hamsters. This began a series of trials and tribulations for the newly captured hamsters. It is somewhat amazing they ever became popular pets. Soon after the hamsters were contained, the mother hamster started eating her young – a preview of a habit that would horrify generations of hamster owners.

Some hamsters escaped. Some died. But enough of that litter survived to found a breeding colony for research. Those animals bred so well, in fact, that they became the founders of a pet industry.

Wild Syrian hamsters remain exceedingly rare and elusive. According to Dunn, only three scientific expeditions have observed this species in the wild, the last in 1999.

A Hamster of Another Color

Most sources state that your pet hamster can trace its lineage back to Aharoni’s expedition. Because all hamsters collected on that trip were from the same litter, this means that pet hamsters show signs of inbreeding, including heart conditions.

This is mainly but not entirely true. One subsequent expedition did collect more Syrian hamsters, which also made their way into the pet trade in 1971.

However, there have also been several other hamster species that have become popular pets. My son’s pet, for instance, is not related to the hamsters captured by Aharoni.

Diggy is a winter white dwarf hamster (Phodopus sungorus), also known by a long list of other common names including Djungarian hamster and Siberian dwarf hamster. These hamsters are like little cotton balls with a light black stripe running down the back.

Winter white dwarf hamsters were first identified by eminent Russian scientist Peter Simon Pallas. Pallas’s name may be recognizable to natural history nerds and birders who know the species named after him, including the Pallas’s gull (and five other bird species), Pallas’s cat and even a type of meteorite known as pallasite. Fortunately, the hamster did not get his name, as he initially identified it as a mouse.

In the wild, the winter white dwarf hamster changes coat color from brown to white, to provide camouflage from predators in winter – much like snowshoe hares. The molt begins in September and lasts a couple of months. Domestic hamsters like Diggy are white year round.

These hamsters are more social than the Syrian hamsters, which makes them more docile in captivity. While we’ve only had Diggy for a short period of time, she’s already quite friendly. In fact, whenever I’ve stalled writing this story, I’ve picked her up and she runs up and down my arms, providing suitable inspiration to press on.

The Plight of European Hamsters

Hamsters may be thriving in homes around the world. In the wild, it’s often a different story. The European hamster is one of the most widespread of the species. It has never been considered pet material, as this species is relatively large and aggressive. In one experiment, captive-bred European hamsters, when presented with a caged ferret, attempted to mob and attack it. The main use of this species by humans is a disturbing one: They were trapped for fur coats. But better regulation (and hopefully, more responsible fashion tastes), allowed the hamster populations to rebound.

But then European hamsters faced an even more significant population decline. The hamsters are not endangered, but their population trend reveals something all too common today: abundant animals becoming much less abundant. A paper published in the journal Endangered Species Research notes the European hamster is “probably the fastest declining Eurasian mammal” and has disappeared from 75 percent of its habitat in Central and Western Europe.

Habitat conversion received a lot of blame, but there is a really intriguing twist. Researcher Mathilde Tissier noted that hamster populations declined as agricultural fields were converted to corn production. When she fed captive hamsters a diet of corn and earthworms similar to what wild hamsters would find in a cornfield, she found something highly distressing: Almost all hamsters ate their litters, every time. As an article in Smithsonian notes, “The corn-earthworm combo was not deficient in energy, protein or minerals, and the corn did not contain dangerous levels of chemical insecticide.”

Tissier’s research led her to a disease called pellagra, caused by too much corn intake. Basically, “Corn binds vitamin B3, or niacin, so that the body cannot absorb it during digestion.” The hamsters were not getting proper nutrients, and were eating their young.

Many have blamed the plight of the hamster on loss of habitat and pesticides, which may certainly play a role. But one of the big cause was a change in diet resulting from new agricultural practices. There’s a lesson here for all conservationists: there may be more going on in wildlife declines than meets the eye.

However, one area where European hamsters are doing well are in cities. Urban parks in Vienna and other cities have become known for their colonies of hamsters, and are often the best places for naturalists to see this species.

Life on the Hamster Wheel

Just minutes ago, Diggy woke up from her daytime slumber long enough for ten minutes of frantic sprinting on the hamster wheel. In the middle of the night, she can run for hours. What is going on? And how does this relate to wild hamsters?

Investigating why hamsters run on hamster wheels leads one to the realm of pet blogging, where you will find plenty of theories but a shortage of science to back them up. For instance, many sources claim hamsters run five or more miles a night on their wheels, but I’ve found no actual evidence. (And I welcome any links to published research in the comments!).

Even among scientists, there are many theories. Many have considered it a behavior done out of boredom or stress, or perhaps a compulsion. After all, no hamster would do this in the wild…would they?

It turns out that a very cool research project investigated this by placing rodent wheels in outdoor settings. The paper, with the great title “Wheel Running in the Wild,” found that rodents (and other species, including frogs), once they learned the wheel, would run on it frequently. Check out NBC News for great videos of wild rodents running on wheels.

Other research found that rats were willing to work to obtain access to a wheel, just as they would for a treat. The body of evidence suggests that rodents, including hamsters, experience the chemical response that we know as “runner’s high.”

So Diggy and I share a hobby in running, and seemingly achieve similar benefits. The physical benefits of exercise are obvious. The research – and this will not surprise any runners – show that hamsters also experience significant mental benefits from running. It reduces stress and calms them.

But there is still a lot we don’t know about hamsters, whether on the wheel or in the wild. There are still discoveries to be made about even the most common creatures around us. Maybe a young, curious pet owner will someday figure out a way to harness the energy potential of hamster power, or find a way to save wild hamster species. Or maybe you’ll just enjoy seeing the world through a rodent’s eyes.

Join the Discussion

33 comments