The finches arrive at dawn.

We watch the waterhole intently, hidden behind a clump of tall grass. We’ve been waiting for hours, huddled together for warmth as we study our bird guides by flashlight.

The birds are tentative. The first few fly down to the edge of the fetid little pool in the dry creek bed. Soon dozens of double-barred finches jostle for space with long-tailed finches and friarbirds.

We’re counting birds for a scientific survey, and I’m so intent on sorting through the mass of polka dots, orange bills, scalloped plumage, and black-and-white stripes, that I almost miss it. One lone bird, dull olive, drinking in the middle of the flock.

It’s a juvenile Gouldian finch — the very bird I’d traveled all this way to see, and one of Australia’s most famous endangered species.

Finches and Fire

Gouldian finches look like they were dreamed up by a 5-year old with a penchant for rainbows and color-blocking: sunshine yellow bellies, deep purple breasts, bright green backs, teal necks and rumps, and either red, yellow or jet-black faces. They’re ridiculous, and wonderful.

I’d wanted to see one in the wild for years, so when my partner and I started planning a vacation in northwestern Australia, I conveniently made sure we’d spend a day birding at one of their known strongholds in the Kimberley region, Mornington Wildlife Sanctuary. But even here, Gouldians are incredibly hard to see.

These technicolor little finches live in the tropical savanna grasslands that stretch across much of northern Australia, where they feed on grass seeds and nest in tree hollows. Unfortunately, this part of Australia is also prime cattle grazing land, and humans have dramatically altered its natural cycles in the last 150 years.

The first hint of trouble came in the 1970s, when trappers capturing wild Gouldians for the pet trade noticed a steep decline in the number of birds. (Trapping is now illegal.) Scientific research soon backed up those observations, but no one knew why the finches were declining. Eventually, scientists realized that the fate of the Gouldian finch — and many other arid land species — is tied to fire.

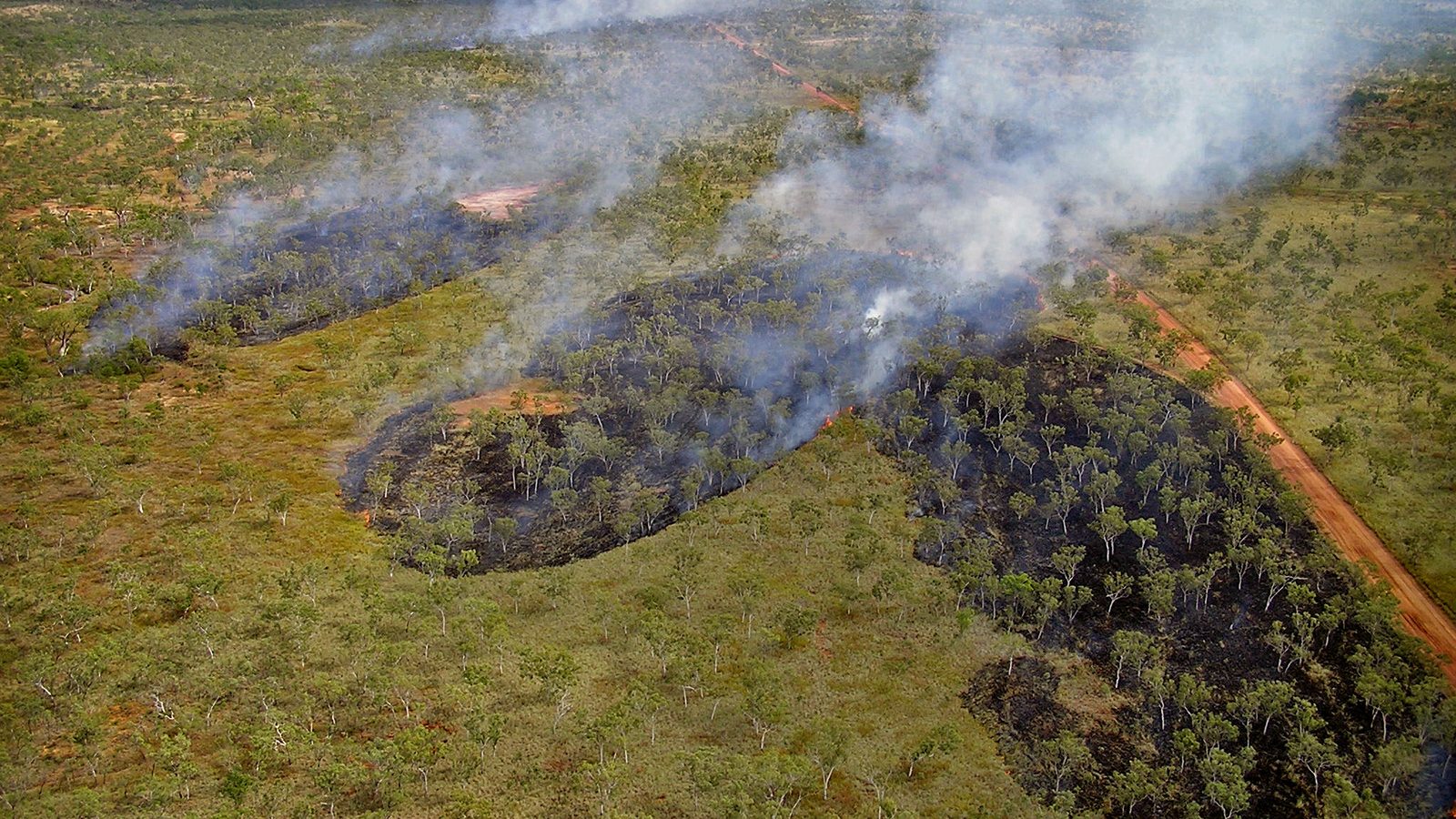

Aboriginal Australians often hunt by lighting small fires to flush out prey. Called fire-stick farming, this method has a dramatic — and positive — effect on the ecosystem. Small, scattered burns created what scientists call a patch-mosaic landscape, where you can find mature savanna, burnt ground, and all of the different stages of regrowth in a relatively small area. Varying rainfall patterns in the wet season further diversify the habitat.

This variety is a boon for biodiversity, and research shows that indigenous fire management both creates habitat for wildlife and increases the population densities of some species.

When Europeans arrived in the Kimberley, they forced Indigenous Australians off their land, ending traditional fire management practices that had been in place for tens of thousands of years. As a result, the fire cycle shifted to larger, hotter bushfires often sparked by lightning late in the dry season. The effect on Australia’s wildlife — including Gouldians — has been severe.

When vast swaths of burned ground replaced the fine patchwork of different grasses and regrowth, it can be difficult for the finches to find food within a day’s flight of their water sources. Large, hot fires burn too much sorghum seed — the most important grass species for Gouldians — resulting in fewer plants and less food for the finches the following year.

Gouldians also have to contend with disease (an airsac mite) and cattle, whose way of grazing hinders the regrowth of grass species that the finches rely on for food.

“In some ways the jury is still out; it’s not clear whether the decline was caused by all of those things or if some were more important, to some degree,” says Sarah Legge, a wildlife ecologist with the Threatened Species Recovery Hub who researched Gouldians. “From the work that myself and colleagues did at Mornington, we feel pretty confident that… fire is part of the issue.”

Legge’s research at Mornington found that Gouldians living in areas with poor fire regimes were less healthy and had higher levels of stress hormones.

Other bird species suffer as well: research shows that almost half of the seed-eating bird species in Australia’s tropical savannas have declined since European settlement. Gouldians are more susceptible to poor fire management than other finches species because they eat fewer types of seed and only nest in hollow trees, which are often destroyed by large fires. “Gouldians have a more strict dependence on grass seeds than other [finch] species,” says Legge.

Early European settlers reported seeing flocks of hundreds or thousands of Gouldians. But today, as few as than 2,500 birds survive, holding on in the Kimberley and in other parts of northern Australia. Mornington Wildlife Sanctuary, run by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy, is considered one of their strongholds. So if I was ever going to see a Gouldian, it was going to be here.

The Great Gouldian Search

We arrived the day before, dusty and hot after three days of driving along a rugged 4wd track. As we checked in to our campsite, a staff member mentioned that tomorrow was the last day of the annual finch census. If we were willing to wake up early, we might be able to join.

At 3:30 the next morning we found ourselves packed into an open-air safari bus with the other volunteers, rattling along a rough road in the heart of the sanctuary. I had spent the previous evening studying my field guide, parsing the differences between masked and long-tailed finches, pictorella mannikins and zebra finches. I wasn’t worried about identifying a Gouldian, but most of the other species were new to me.

“Troy, Justine, you’re up!”

Our instructions: Climb down the creek bed to the right and look for a large, diamond-shaped rock. Beneath it is a small waterhole. Count every grain-eating bird you see from 5:30 to 7:30, and then wait for the bus to pick you back up. Don’t bother any snakes, and DON’T wander off.

Waterholes are the ideal place to survey for Gouldians, because grass-eating birds need to drink more than other species due to their diet. Flocks typically drink first thing in the morning before heading out to forage, which provides a (relatively) easy way to locate them. In preparation for the finch census, Mornington staff and scientists walked nearly 100 kilometers of creek beds in the week before to find waterholes and assess which ones were the best drinking sites.

The finches arrived just after 6:00; first double-barred finches, then zebras. Counting is hard work, but we fall into a rhythm. We have to watch when a new flock arrives, identify and count the number of each species, then break down the number of males, females, and juveniles. It would be easy if the birds sat still. But they don’t. They drink, fly to the nearby tree, come back down, hop around the mud, drink, and repeat. And then the whole flock takes flight without warning.

When the first Gouldian appears, we allow ourselves a very quiet celebratory high-five, so as not to scare the birds. More and more turn up, but they are all juveniles. And, at the risk of sounding like a bird snob, I’m not satisfied.

Another flock arrives, this time with a female. (Females have identical coloration to males, but the colors are more muted.) And then — midway through counting a flock of pictorella mannikins — a gorgeous male Gouldian hops into view.

“Black-headed male!” I whisper-shout to Troy, who immediately stops writing and grabs his binoculars. It takes all my self control to stay focused on counting. Birding for rare species is always a gamble; some days you win, most days you lose. And having missed out on the last several rare species I searched for, it was beyond thrilling to see my first Gouldians.

But then it got even better.

Just as our last flock of birds came in to drink, we spotted a male with a brilliant scarlet face drinking alongside the others.

Gouldians come in three different color morphs: black-headed individuals make up between 70 to 80 percent of the population, while the remaining 20 to 30 percent have cherry-red heads. The third color morph — golden orange — occurs in only one in every 3,000 birds. The color differences are caused by genetic variations, akin to differences in human eye color.

To see two of the three morphs together felt like winning the birding lottery.

Burning Country for Conservation

Indigenous communities across the Kimberley are leading efforts to restore indigenous burning practices, with support from conservation and science organizations. In some cases, pastoralists have also adopted early dry-season burning practices, learning from the experience and knowledge of indigenous fire managers.

“Healthy fire regimes help not only Gouldians, but a whole range of threatened mammals,” says James Fitzsimons, the conservation director for The Nature Conservancy in Australia. Like the Gouldians, many of Australia’s small mammal species have declined dramatically (or gone extinct) as a result of unhealthy fire regimes.

For Gouldians, the good news is that fire management has a clear and positive effect on finch health. Legge’s research at Mornington showed that when traditional burning practices were reintroduced, finch health improved. And recent research shows that early dry season fires increase the nutritional quality of sorghum seed, which in turn increases finch breeding success.

Deliberate burning early in the dry season also has a tremendous ability to combat climate change, because these cooler, smaller fires reduce the fuel load and release less of the carbon stored in grasslands.

TNC helped design a low-emissions burning method that is now being used across 32 million hectares of northern Australia, abating 13.8 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent over the next 7 to 10 years. These sales will generate an estimated $163 million AUD for indigenous landowners and pastoralists to manage their lands.

When 7:30 came and our count was done, we’d spotted an incredible 77 Gouldians, most of which were juvenile birds. We’d also recorded five other finch species, including pictorella mannikins and crimson finches.

As we clambered back into the bus, the other volunteers asked us how it went. Troy replied: “We’re not sure what a good morning is like, but we think we did really well?”

Everyone’s faces fell. We learned that we were the only ones to find Gouldians that morning, and our total of 77 birds was one of the highest counts of the survey. Some volunteers had driven across the country to participate and not seen a single Gouldian in five days.

And we were the jerks that waltzed in at the last minute. We felt horrible.

The other volunteers’ barely concealed misery highlights just how rare Gouldians are: We were birding in a noted stronghold on healthy, well-managed country, and the survey was specifically designed to find and record finches. And yet some volunteers walked away empty-birded.

But if indigenous communities, conservationists, and land managers continue their work, there is hope that Australia’s rainbow finches can survive.

i am coming this year 2023 in july, hoping to see gouldians

Basically this suggests that the Australian bans on fires is the cause of the horrific fires of last year? Those aboriginal people had it all sussed but the fools thought they knew best…..will we ever learn? We have same here in UK where small organised fires on moorland have been replaced with massive damaging random fires….