It’s early fall, late in the day. I’m pedaling through a dry meadow. My youngest son is whining about the heat a few pedals behind me. When we reach timber, I drop my bike in the dirt and drop on a log in the shade. Just as I bark at my son to do the same, I hear another bark, more like a kazoo without the rattle of wax paper under pressure. It’s a female elk, a cow. I don’t see her, but I hear her. I bet she’s calling for her calf to move away from us just like I’m barking at my son to move away from the sun. That’s my best guess. Cows make all kinds of calls, but officially knowing what they mean is difficult.

“We started to work on cow calls and we had to put them in the too hard pile,” says Jennifer A. Clarke, professor of wildlife biology and behavior at Unity College. “They’re talking about so many different things. Females worry about calves, other females and maybe the route.”

Adult male elk, bulls, are much easier to decipher. They scream for two reasons: fights and females. Yellowstone National Park is known for its aggressively big screamers during the rut, elk mating season.

Tourists visit Yellowstone through October to watch 700-pound animals with bulging racks make a bugling ruckus. Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado is another popular place to catch the fall spectacle, but you don’t need a national park for this spectacle.

In the 19th century, the elk’s range was reduced to a few places in the Western United States. They are now not only found in abundant populations in the West, but have also been reintroduced to many eastern and midwestern states. You can find elk herds in Kentucky, West Virginia and Wisconsin. Clarke is researching wild elk in Pennsylvania this fall. She studies animal communication.

“Bugling elk is a major attraction, but to be honest, none of us know what we’re listening to,” Clarke says. “There’s not one single study that has confirmed what purpose bugling serves and that’s the focus of my research.”

The Sound

There’s nothing friendly about a scream mixed with high-pitched whistles and low-belly grunts. The sound raises concern and raises the hair on the back of your neck. It’s alarming and that’s the point. The bull is making sure the forest knows he’s coming and his intentions are serious. Bugles are alerts, but each bull has its own way of delivering that alert.

“Bugles are unique so you can recognize males based on their bugles,” Clarke says. “One of my graduate students named bulls after her ex-boyfriends. We’d know when we heard Joe without actually seeing Joe.”

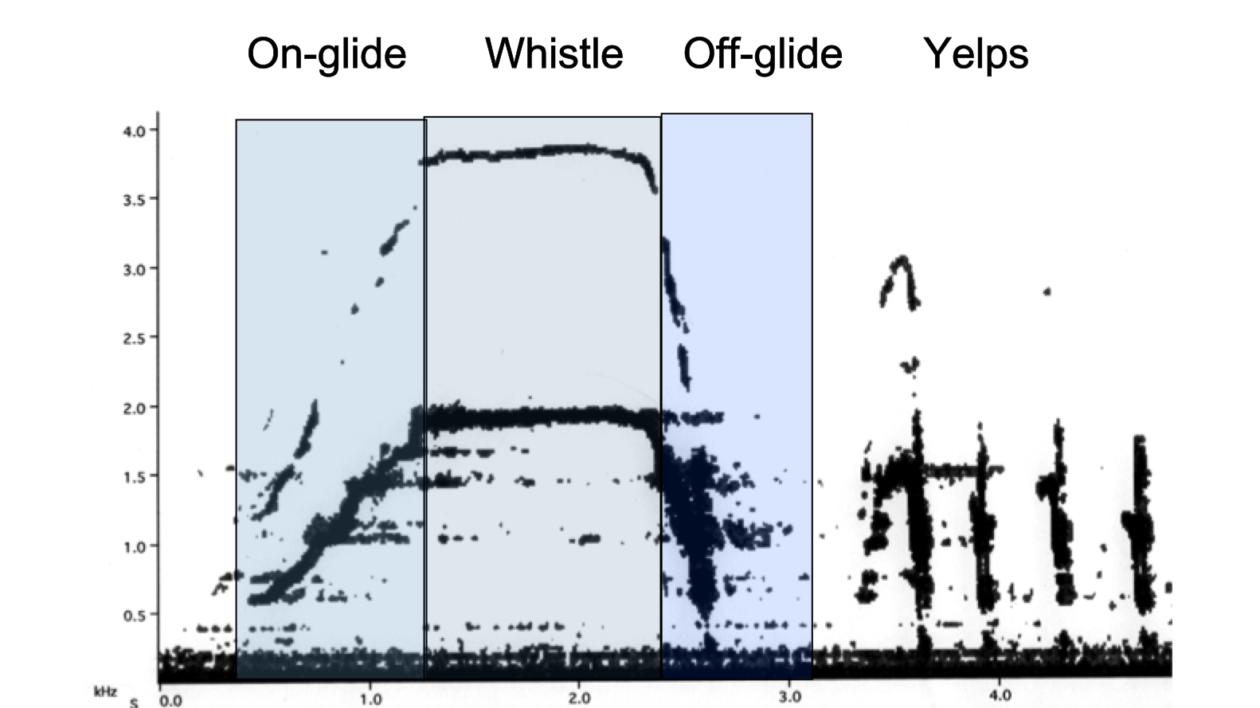

Translating a bugle is done with a spectrogram and it’s easier to look at than to listen to. A spectrogram is a picture of sound. Look at the scream of an elk on paper and it follows a pattern. First, there’s the rise in pitch to the whistle, the on-glide. Next, the whistle holds for a second or two followed by a drop in pitch, the off-glide. Sometimes the off-glide transitions into multiple grunts known as yelps. Yelps are optional. They’re like email attachments. You don’t always need them, but when you do they reinforce your message and without them, your message is incomplete.

The low notes of a bugle are pretty expected. Elk are large mammals and, like a large drum, the larger the surface the deeper the tone. The whistle is surprising. It’s an extremely high pitch, something that usually comes from a small squeaker like a prairie dog.

The Sight

You can anticipate an oncoming bugle by the way a bull moves. An adult male elk walks with its neck relatively vertical, despite its heavy antlers. When it’s going to bugle, its neck reaches a nearly horizontal plane. It looks as if its snout is connected to a leash that’s being tugged so the rest if its reluctant body will follow. The animal has the ability to pull its larynx deeper into its body, which is why it elongates its upper half. The deeper the larynx goes, the deeper the sound is, which correlates with how angry the animal is.

“When they are upset at another male, they put a lot of aggression in that whistle,” Clarke says. “They pull their larynx into their throat and that pulls that tone into a roar.”

On cold mornings, you’ll also see steam leave a bull’s mouth and nose while it’s bugling, which leads Clarke to believe smaller air passages of nostrils or front pouch of the lips may have something to do with the whistle that’s too high pitched to normally be coming out of an animal so large.

And the yelp sometimes added at the end, that’s visually obvious too. It’s the trunk of the bull’s body inflating and deflating like bellows blowing air onto a fire. The purpose of the yelp is yet to be determined.

The Signal

The response to a bugle is how other animals interpret the signal. It’s how you figure out what’s going on during a sound off.

If a bull is too close to another bull’s herd, there’s a lot of aggression in the whistle. If a female is straying too far from a bull’s herd, the aggression is displayed in the off-glide of the whistle. It’s a dual-purpose production. Get back you brute, and ladies fall in line. The brute should eventually back off, but the ladies don’t always fall in line.

“That’s something about elk behavior that some people misinterpret,” Clarke says. “The male doesn’t direct where the herd goes. It’s the lead female that decides that. The male runs around trying to keep the ladies together as they choose where to go. They see mom or a girlfriend in another herd and they want to run over and visit. That’s when the conflict begins.”

In the long run, deciphering bugles could make it easier for scientists to track population trends in a less invasive way. You don’t have to touch wildlife to record its calls, but you have to touch wildlife a lot to attach a trackable collar.

For now, use what scientists have learned so far to translate the screams you hear, and see, when you’re in the woods this fall.

I LOVED this article!! Thanks!