Once a month, June through September, my truck transforms into the batmobile as I go looking for bat signals. I drag my family along so I can claim the outings as trifecta trips.

First, it’s family time. Even if my youngest son falls asleep soon after we start. Second, it’s training time. My eldest son, who has his learner’s permit, may be the only teen doing his required 10 hours of night driving going 20 miles an hour on a dirt road. And third, my husband and I are certifying as Idaho Master Naturalists. In addition to 40 hours of class time, we have to log 40 hours of fieldwork. Looking for bats as citizen scientists satisfies 16 of those 40 hours. That’s why we slowly drive back roads along Idaho’s South Fork of the Snake River for four dark hours at a time.

“I don’t mind the late nights so much,” says Brenda Pace, East Idaho Bat Survey volunteer coordinator. “As long as I have a day to recover.”

Pace is a retired archeologist with an overactive interest in night fliers. She’s in charge of eastern Idaho’s annual bat surveyors, which collect data that eventually ends up on the desks of official scientists with agencies like Idaho Department of Fish and Game and Bureau of Land Management. Idaho has 13 types of bats. Through surveys, 12 of the 13 are now documented.

“We don’t count the population,” Pace says, while showing us how to install bat-signal equipment on my truck with only a speck of daylight left. Surveys start a half hour after sunset. “This machine helps identify species and when that species moves.”

Bats cross our path as soon as my son starts driving. We hear the recorder jabbering in the first mile of our 19-mile route. The recorder, a.k.a. bat detector, is small but vital. It’s a yellow rectangular box a bit larger than your hand. It has a handful of red blinking lights on it. ‘On’ and ‘record’ are the same button so when the red lights are on, the box is recording.

Bats use echolocation, sound waves bounced off prey, to locate food. That pitch is beyond human audible range. That’s why the little yellow box is vital. It slows down bat signals by a factor of 10. Slow down the sound and it will register in human ears creating the electronic noise we listen to in the truck. The melody is a funky cross between techno keyboard and electronic drums with a few screams thrown in to break up the monotony of the repetitive beat. During the wild’s ruckus, we sometimes see wings flutter in front of our headlights, but mostly we just hear what’s on the other side of our windshield.

“I think we’re really probing for aliens,” my teenage son says while commanding our batmobile along the wide curves that follow the river corridor. “That screech is going to give me nightmares,” my youngest son adds as he dozes off.

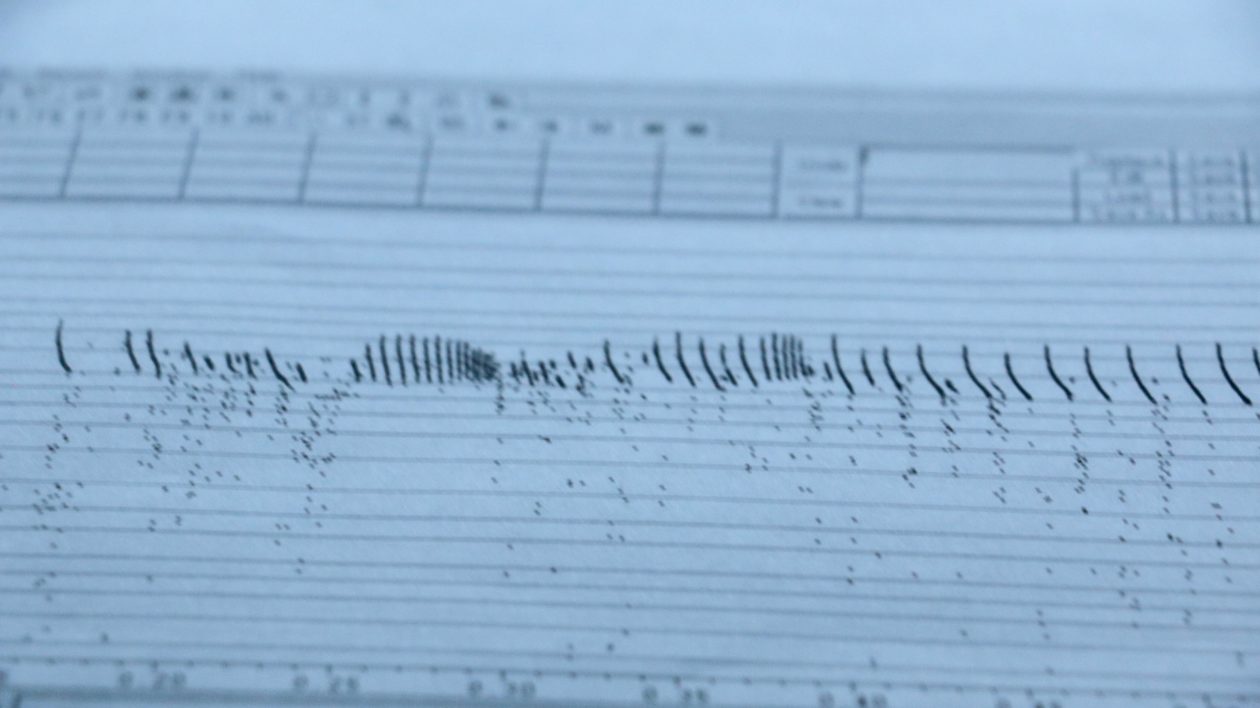

On paper, the screech looks like an earthquake measured by a seismograph. Scratches of black ink spread wide mean a bat is sending out signals in search mode. Scratches scrunched together tight indicate a bat is zeroing in on prey for feed.

Our counts run high by the river, with 42 bats signals recorded in one night. That’s the second highest among 24 routes in our region. Bear Lake on the southeast Idaho border has the highest rate with 71.

The producers of those signals, bats, pass quickly. That’s why you must cruise ever so slowly through the night. It’s like your scuffing around in an alley for trouble, but with a large studio-like microphone stuck on the roof of your vehicle, wires hanging out the passenger window and hazard lights flashing.

Other than deer, there’s not much traffic on dirt roads in the dark, but what does come up on you is never going 20 mph like you are. Our hazard lights hopefully offer fair warning that there’s serious science going on. This kind of research has led to rare discoveries like the bat recently found in a cave west of the river. It was originally banded in the 1980s.

“It astounded me they lived that long,” Pace says. “People think bats are flying mice, but they’re really flying grizzly bears with a lifespan like that.”

That lifespan shrinks with interference. White nose syndrome is a known problem for bats nationwide. It interrupts their hibernation phase causing them to wake in winter and subsequently starve because they’re awake and using too much energy when they should be sleeping.

Wind turbines are a lesser-known problem. Do bats bounce signals off the blades, mistake them for food and close in or do the blades create a force field that sucks them in? U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) is trying to figure that out but either way, bats die on wind farms. Knowing where bats go, and when, could help with designating wind farm locations and when the turbines on those farms turn.

“Bats only forage when the wind is below 7 mph,” Pace says. “Stopping turbines when the wind is below 7 mph saves bats.”

Wind. That’s the other thing our batmobile monitors. I use the weather app on my phone to track wind and temperature. I also use my eyes to visually measure cloud cover and moonrise. There’s a running list of other stats we collect too, including the exact time when we get lost, 10:36 p.m. And the exact time when we find ourselves again, 10:38 p.m. The data processors need to know we missed a turn so they don’t count calls we accidentally collect while we’re off route.

We use our eyes to get ourselves back on track, but mostly it’s our ears that are engaged. Sounds of bat nightlife are new and intriguing, if not also nightmare inducing as my youngest son twitches in his sleep with his head in my lap while my hand holds the yellow screech box. We continue on down the road collecting more bats that we cannot see.

Bats are essential for keeping harmful bugs under control. Every creature on this planet has a purpose and needs to be respected and protected.

Really fascinating – had no clue till I read an article on here that there were so many different kinds of bats! We sure do need to know more about them – in order to save them!