Recently, I was warned by a backpacker on an Idaho wilderness trail that my family’s intended destination was overtaken by badgers. The man grimly reported that he had seen eight badgers just by his campsite.

We found the spot, exactly as he described it. But the meadow was home to a family of hoary marmots, not badgers.

Spending a lifetime in the outdoors, I’m used to wildlife misidentification. I am not talking about the problems associated with differentiating gulls or warblers – even many expert naturalists struggle with these. Nor am I talking about distinguishing shrew species, many of which can only be told apart from their dentition.

No, I’m talking about misidentifying common and/or iconic animals. Many of these errors involve animals that are large and at first glance seemingly unmistakable (like grizzly bears and mountain lions). Others are abundant in national parks, but also commonly confused (ground squirrels and prairie dogs).

For your reference, here is a field guide to commonly misidentified North American wildlife. I provide a brief overview as well as resources for more in-depth information. For space reasons, this edition will focus on mammals. If it proves useful to readers, I’ll post future “field guides” to misidentified snakes, fish, birds and other critters. Let me know in the comments.

The Ground Rules To Avoid Misidentification

You don’t have to be an expert to avoid the most common misidentifications. You can start by simply following these three ground rules.

If in doubt, you probably saw the least exciting option.

This may seem basic, but you’re more likely to see common animals than uncommon ones. Therefore, you have to rule out the most boring possibility first, before assuming you just saw something really awesome.

I hear a lot of sightings where people “think” they saw something really cool – say a mountain lion or a wolf – in an extremely unlikely area. Then it turns out they had a quick look or were in thick forest. If you see a wild canine running across a field outside Denver, it’s most likely not a wolf but a coyote (or a German shepherd).

Beware “barstool biologists.”

Walk into nearly any bar in rural America, and you’re likely to hear some version of: “The state biologists spend all their time in front of computers. I’m out there in the woods, and I know there are lots of cougars (or whatever) in these woods.”

Some colleagues call these folks “barstool biologists.” Know how to find reliable sources of information (this applies to other aspect of life as well). The slightly inebriated guy who tells you about the black panther his cousin’s friend’s coworker’s niece saw in suburban Rhode Island is not a great resource for wildlife ID. I sincerely hope I didn’t have to tell you that, but judging by some wildlife reports I see, it is worth noting.

Field guides and nature apps are your friend.

There is a wealth of great information out there. A field guide is money well spent before any national park vacation. These are written and illustrated by experts and will not only help with common wildlife, but also help open your eyes to other wonders of the natural world.

Many fine apps exist that can also aid in identification, and also help you report sightings (which can be corrected if necessary by skilled naturalists). There are field guides and apps for nearly every possible nature sighting. Using them adds immeasurable enjoyment to your time outdoors.

With that in mind, let’s go over some of the most commonly misidentified wildlife in North America.

Black Bear or Grizzly?

Everyone traveling to Yellowstone or Glacier wants to see a bear. But what bear is it?

The most common reason for misidentification lies with this fact: Not all black bears are black. They come in a variety of colors including brown and cinnamon, both of which can look like grizzlies. Further, black bears are more likely to be brown in areas with grizzlies. So color is not a reliable way to tell species apart.

The first thing to do is to look for a hump. Grizzlies have humps; black bears do not.

Black bears also have a face with a nose that slopes straight down, somewhat like a dog. A brown bear’s face is concave or “dished.” It looks more, well, like a bear face. Finally, look at the ears. The black bear has tall, pointy ears compared to the grizzly’s rounded, less conspicuous ones.

Get Bear Smart has an excellent guide on bear identification and a quick search will yield many other resources, including fun photo tests to try your ID skills.

Mountain Lion or Bobcat?

This one is easy: look at the tail. A mountain lion’s tail is long; the bobcat’s is short. That should immediately rule out the possibility of most misidentification. The mountain lion is also very large, weighing as much as 150 pounds. A bobcat tops out around 35 pounds. Bobcats also tend to have spots.

One challenge can come with trail cameras, as the images can be less-than-clear and it may be difficult to tell scale. There is a social media hashtag #CougarOrNot run by experts that can help. Reviewing that site can help you tell the difference.

Mountain lion sightings are rampant in the eastern United States, but scat, trail camera photos, kill sites and other evidence is lacking. If you think you’ve seen a mountain lion in the East, first refer to Rule #1 in this blog. A lot of sightings are in thick woods, or at night. And lot of “mountain lions” turn out to be thin bears, dogs, or coyotes.

In some areas, bobcats can be confused with the similar-looking but much rarer lynx. Here’s a good resource for telling the difference.

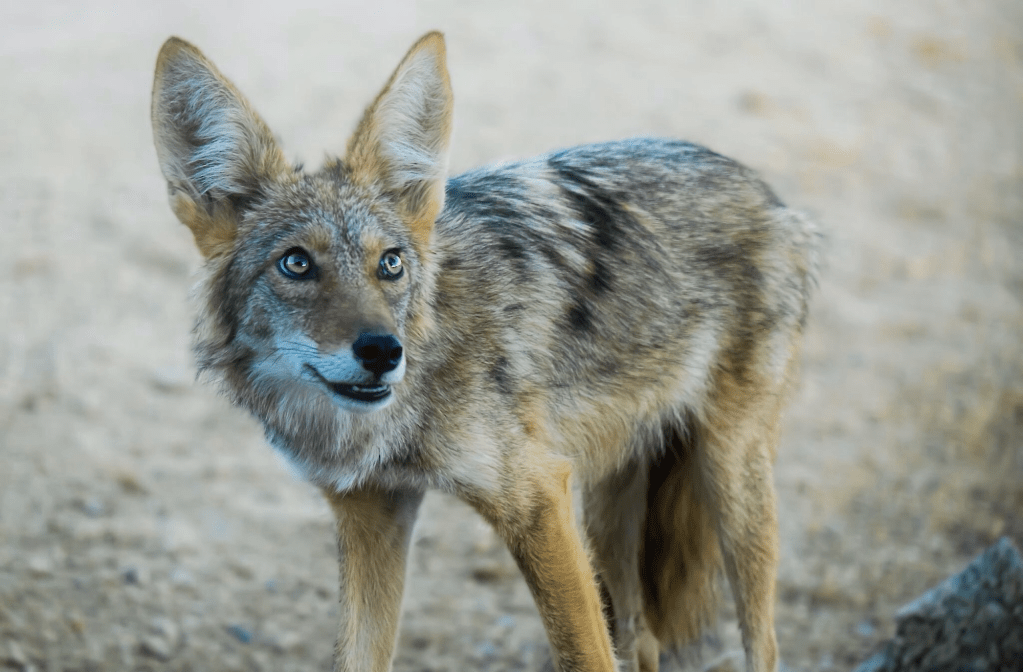

Wolf or Coyote?

Telling wild canines apart in the wild can be tough. A wolf is much bigger, which doesn’t help if you’ve never seen a coyote. The wolf’s face is broader and ears more rounded than the coyote’s narrow face and pointy ears. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife has an excellent page that breaks down differences in appearance, vocalizations and tracks.

Understanding habits is an important part of wildlife identification. Coyotes are very adaptable and can be found in agricultural areas, suburbs and even cities.

In the Midwest and eastern United States, canine identification gets confusing. Red wolves are very difficult to tell from coyotes (and red wolves are also very rare). This is compounded by the fact that eastern coyotes actually contain eastern wolf genetics. And there is an eastern wolf that lives in parts of Canada. Clear? My previous article on wolf hybrids breaks this down for you. Any mammal field guide and a basic knowledge of range and habits can help you make the most educated ID.

About That Badger

A badger is a distinct looking creature, but many people find mid-sized mammals confusing. For badgers, look for the black-and-white face and long claws. It digs ground squirrels out of their burrows, so it is powerfully built.

A marmot is the western version of the woodchuck. It’s an herbivore and lacks the pointy snout and stout claws of a badger.

In recent years, fishers have been reintroduced in the eastern United States and are thriving. But many folks are unfamiliar with them. If you picture a large, furry weasel, you will get the right idea. Wolverines are very rare and hard to see, and are not found in the eastern US.

Martens have similar tracks to fishers and favor the same big woods habitat. But they are smaller, redder, more streamlined and have two noticeable black lines that go from the top of their eyes to their forehead. ProTrails will help you distinguish these cool animals: and count yourself as lucky if you see them!

Chipmunk or Golden-Mantled Ground Squirrel?

Chipmunks are common backyard animals in many parts of North America. When people camp or picnic in the West, they often remark on the obese, super-sized chipmunk mooching snacks. Except it’s not a chipmunk. It’s a golden-mantled ground squirrel.

I hear this misidentification every year. It’s easy to avoid. If you see a gigantic chipmunk (double or triple the size): it’s the similarly striped golden-mantled ground squirrel. And like chipmunks, it loves to hang out anywhere it can pilfer food from outdoor recreationists.

If you really want to put your wildlife identification skills to the test, by the way, try Western US chipmunks. In most places east of the Rockies, there is one species, the Eastern chipmunk. From the Rockies west, there are 23. Identifying them can test even skilled mammal enthusiasts but it’s a worthy challenge, as the species are active in the daytime and fairly easy to locate.

Many have striking differences. A chipmunk quest to see all the species would take you to varied habitats in some of the continent’s most spectacular places, from the Olypmic Peninsula to the Redwoods to Joshua Tree to Arches and beyond.

Prairie Dog or Ground Squirrel?

“Look at the cute prairie dog!”

It’s a proclamation I have heard at the Grand Canyon, the Yellowstone Geyser Basins, and on Idaho’s sagebrush flats. In all instances, the “prairie dogs” were actually ground squirrels. This is an easy mistake to make. They look similar. Prairie dogs prefer grasslands and live in large colonies. Ground squirrels (usually) live in smaller colonies and can be found in a wider range of habitats.

There are several species of prairie dogs and multiple species of ground squirrels. These are common animals to see on the classic Western US road trips. They also exhibit quite fascinating behaviors.

If you’re interested in learning more, I highly suggest Tamara Hartson’s field guide Squirrels of the West. It’s compact and will aid you in identifying not only ground squirrels and prairie dogs, but also marmots, tree squirrels and chipmunks.

These small mammals need our help as they are heavily persecuted and unappreciated. Learning a bit about them can assist in their conservation.

Finally, You Never Know…

I’m sorry to say that it was probably a bobcat in your neighborhood, not a cougar. But you never know. Learning a bit about wildlife identification can actually help you know when you really do see something special.

When a mountain lion went on walkabout from South Dakota to Connecticut, with many stops along the way, many initial observations with discounted. This is because there are so many fake lion sightings that no one could believe there were real ones. (I highly recommend Will Stolzenburg’s Heart of a Lion for a compelling account of this animal).

A wolverine lived in the wild for several years in Michigan (it was a zoo escapee, but it really was a wolverine). Weird things turn up in weird places.

Unfortunately, as with the fairy tale, people who cry wolf (or mountain lion, or wolverine, or bigfoot…) don’t help. They cause biologists and other experts to discount sightings because they’re so used to the unreliable ones.

Carry a field guide, rule out other possibilities and report your cool sightings. You’ll be helping conservation and citizen science – and have fun doing it.

Due to limited space, I can’t list all confusing wildlife identifications. If you have questions about a creature you’ve seen, describe it in the comments and I’ll do my best to help.

Great article (as always) Matt! As an Interpretive Naturalist and a dedicated field herper I would like to wish you well on the future article regarding misidentified reptiles. As you may well know, all snakes found on land are copperheads and all seen in an aquatic setting are Water Moccasins (I hate that name btw, I prefer to use cottonmouth)! I look forward to these “misidentification” articles as well as the rest of your musings. If you’re ever in the Land Between the Lakes area of Western Ky./ West Tennessee be sure to stop by Woodlands Nature Station for a visit! Our Red Wolves are gorgeous!

Great article as always Matt. As regular visitors to Yellowstone, we have seen first hand many people confusing coyotes for wolves or black bears for grizzly bears. I agree that beside a lack of knowledge the most likely reason is that people WANT it to be the more exotic of the two similar species. Both are certainly easy mistakes to make for people that haven’t seen any of these animals in the wild before. So, we always take “tourist” IDs with a grain of salt.

But, that attitude also hurt us once. We were walking on the boardwalk to Hidden Lake at Logan Pass in Glacier National Park when we stopped and chatted with a couple of obvious tourists. They were excited because “We just saw 3 wolverines running through the meadow”. Well, we just smiled and asked if they were sure they were wolverines and not something like a marmot. No, they were positive they said. Of course, we assumed that they had no idea what they were talking about and had just seen 3 marmots running around. After all, what are the odds that 3 wolverines would be together?

After returning from the hike, we went into the Logan Pass Visitor Center and starting chatting with a ranger. We mentioned the “wolverine” sighting and she said that they were wolverines! The couple took a cell phone video apparently and showed it to that ranger. It was a mother and two juvenile wolverines, plain as day just running around close to the boardwalk she said.

Of course, to this day, we are kicking ourselves that we didn’t stick around that area and try to see if the “wolverines” were still around. That was likely the best shot we will ever have of seeing one.

We will definite not dismiss exotic wildlife IDs so readily in the future…

I just learned a lot here . I’d heard the word marmot in a fiction short story, thought ground squirrel was a regional label for chipmunk, and wolverine was a person from Michigan.

Thank you for the helpful article. Have ordered the squirrel ID book.

What we really need is a quick reference field guide to help us differentiate between “Barstool Biologists” and truly experienced and wise woodsmen! This would be very helpful when visiting a place with which I am not familiar.

Pine martens are in Europe. We have American martens in North America.

You might want to add a photo of a kit fox to this list. We have them where I live in California, even within the city! Great article.

Awesome post! Next can you talk about how not all black spiders are black widows, not all brown spiders are brown recluse and not all snakes are [insert venomous species here]?

I live summers on the North Bruce., Ontario One night, I was aroused from sleep by a quivering ASCENDING call outside my window. Could it have been a Fisher? (I ruled out owls, it seemed to be in close proximity in a treeless opening. )

It’s my understanding that fishers don’t make much noise. When I moved to New England my neighbors commented on hearing fishers all the time but what they though were fisher calls actually came from foxes. The common “wisdom” is that fishers sound like a woman screaming and foxes are silent. Which is pretty much backwards.

We do have fishers in the neighborhood and I’ve been lucky enough to see them, but we also have foxes and coyotes that are much noisier at night.

Sunfish are the most misidentified animal in my part of the world. Any help on a solid resource for bonafide sunfish ids?

I am a big fan of sunfish (currently trying to catch all the species). I agree; they are often misidentified and most do not realize the diversity. Many people just call them all “sunfish” or “bluegill.” I highly recommend Peterson’s Field Guide to freshwater fish. It’s an excellent resource on sunfish and other species. The site roughfish.com has a species section that I have found very helpful as well.

Please post much more on identifying species! The information and photos are wonderful!

Great article. I’m a biologist in Texas and surprisingly, one of thr most common misidentifications I see is housecats and mountain lions. It seems impossible to mistake animals of such different sizes, but I think size can be very difficult to gauge through cameras and binoculars.

Thanks again!

Jonah

I will share a little story that I think has a good lesson that can be useful.

Many years ago I was on a very dark road, dead quiet, at the base of the mountain hoping to call in owls. I got out of the car and heard a twig snap. Quickly I located the source with a flashlight. It was motionless and well illuminated with the flashlight. I would have sworn I was staring at a mountain lion. I keep looking and finally realized I am staring at a very ordinary White-tailed Deer. My mind simply blocked out seeing the ears, even though well lit up. When I did finally notice the ears…I realized what I was looking at.

I have wondered, had the deer moved instead of standing there long enough to realize it was a deer…would I have wondered if it was a lion, or would I be certain I saw a lion. Idunno.

A few things like this has happened over the years. It was a good lesson and I’ve learned very quickly that a proper identification often requires more than a split second look. Just occasionally, a quick look may give a totally wrong identification. As a birder and outdoorsman for 45 years, I know when I am correct or fooled. I can see how people are easily fooled. It would be interesting understanding the psychology going on here.

Thank you so much for this article, particularly for the recommendation of Hartson’s Squirrels of the West. I’ve long realized that my knowledge is shockingly outdated (in my Desert and Montane Ecosystems class 37 years ago antelope ground squirrels were still placed in genus Citellus, for example), but I don’t have the funds to buy expensive books. Having a recommendation like that from someone who knows what they’re talking about made it possible for me to find a used copy for less than $4 delivered to my door.

Huzzah!

Awesome article!