This story was reported before the February 2021 military coup in Myanmar. Details within may be outdated.

I wake to the sound of teak bells. Their two-part chimes echo through the logging camp as I roll over in my sleeping bag, huddled in against the chill. The bells grow louder. I hear yelling. Then a thud. And finally a loud trumpet that can only mean one thing: the elephants are back.

Stumbling out from beneath my mosquito net, I look up to see a full-grown bull elephant sauntering slowly up the road, carrying an entire 10-foot-long log in his trunk. It’s our morning firewood delivery here in the Elephant Camp.

This magnificent tusker is just one of thousands of timber elephants used to log timber from Myanmar’s rugged mountains, a practice that’s more sustainable than using bulldozers. But now this legacy is threatened by both the illegal wildlife trade and replacement by mechanized tools.

From Battlefields to the Logging Camps

Elephants are an inextricable part of Southeast Asia. From the elephant-headed Hindu deity Ganesha to the legendary timber elephant Bandoola, they permeate the region’s culture, religion, and history. “Elephants are our country’s royal treasure,” says Burmese conservationist Tint Lwin Thaung.

Most valuable of all is the white elephant — either a true albino or leucistic elephant with pale pink or grey skin — prized by Burmese and Thai rulers. “For thousands of years all of the kings in the region fought and competed with each other to own the white elephant, because owning that was a source of power,” says Tint Lwin Thaung.

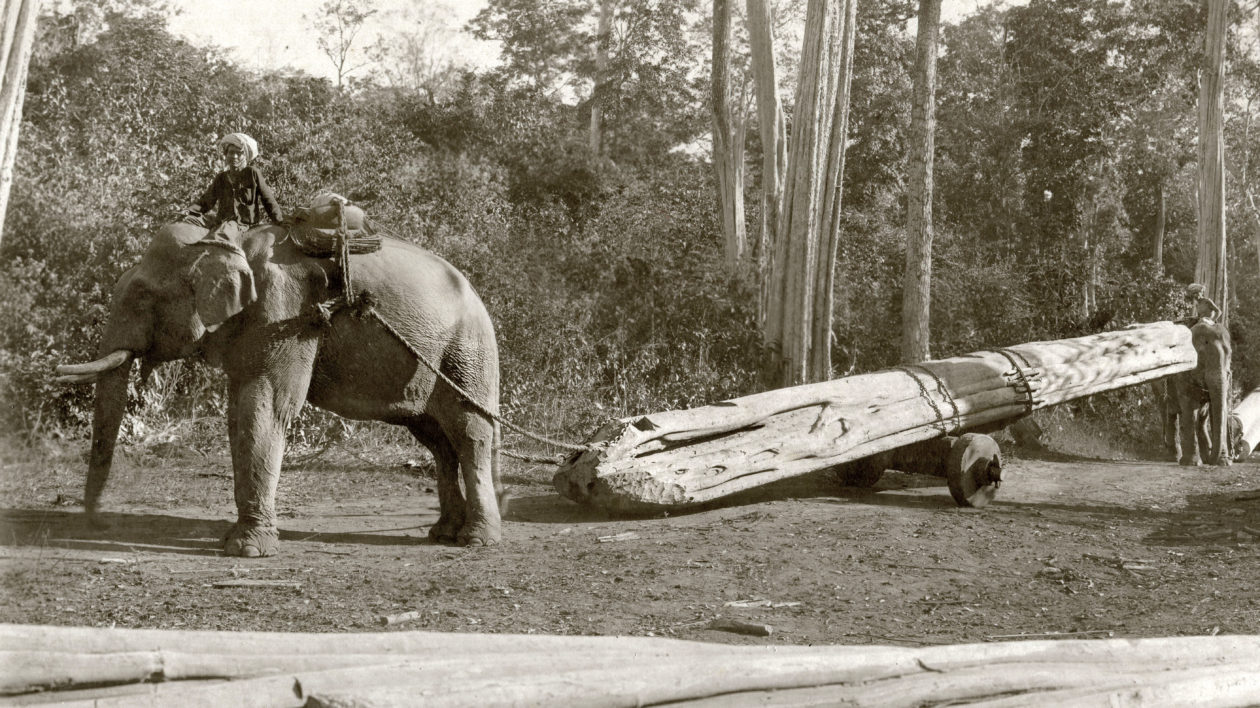

After Burma’s last king fled into exile, the British drafted elephants to work in the lucrative teak-logging industry. A century later, Japanese forces invaded Burma just weeks after bombing Pearl Harbor. Those same timber elephants worked behind enemy lines, braving gunfire and slaughter to build the roads and bridges the British army needed to retake control of the country.

I watch as the elephant walks closer, a mahout caretaker perched jauntily on his neck, feet hooked behind the bull’s pink-and-grey speckled ears. At the edge of the campfire, the mahout shouts a command and the elephants drops the log into the ashes with a thud. Then the mahout pulls a sticky, amber-colored ball of tamarind fruit and peanuts from his pocket. The bull curls his trunk backward for the treat, slobbering contentedly as he chews.

Following another command, the elephant drops to his knees to let the mahout slide off. But as a second mahout climbs on, the bull jumps up and dashes off through the camp, trumpeting loudly and dragging his chains behind him. Both mahouts chase after him, laughing and shouting. We turn back to the fire and start preparing for another day in the forest, where we’re gathering data on biodiversity and freshwater health.

Myanmar has the world’s largest captive elephant population, and the vast majority of them still work as timber elephants. About 3,000 are owned by Myanma Timber Enterprises (MTE), the state organization responsible for harvesting timber, while the other 2,500 are owned by private contractors that hire them out to loggers. All elephants are registered with the government, which keeps record books that document their work and medical history.

The six or so elephants in our camp work for MTE, indicated by a large star-shaped brand on their flanks. Work starts at dawn, when the mahouts venture into the forest to round up the elephants from their nightly foraging. By mid-morning they’re back for their daily bath, after which the elephants are fitted with a bark harness worn across their breast and back.

Then both elephants and mahouts trek into the forest, where the loggers are felling teak, ironwood, and rosewood. MTE workers trim small branches from the trunk, wrap chains around one end, and then hitch the log to an elephant. Guided by their mahouts, the elephants drag the log through the forest — often up and down incredibly steep and muddy ridges — to a central clearing. Later, the loggers build a road to that location to load the logs onto a truck.

A typical elephant can haul about 20 1-ton logs each day, says Soe Min Oo, an 18-year-old mahout working in our camp. His elephant, Zar Win Win, is 34 years old and in her prime years as a working elephant. If she stays healthy, she could work another 20 years. “She likes to eat bamboo shoots and leaves,” he says, “and she is well trained by her previous mahout.”

Speaking through a translator, he tells me that he fell in love with elephants as a young boy, when he’d watch them working in the forests. He’s worked as a mahout for one year, helping Zar Win Win navigate across dangerous mountain terrain to safely transport each log. Soe Min Oo says that she finishes each day exhausted, and it’s his responsibility to look after her.

Though the elephants work hard, they’re still healthy. Regulations limit their labor to 5 to 8 hours per day, 5 days per week, with maternity leave and regular veterinary care. Studies show that timber elephants are healthier and live twice as long as elephants in European zoos.

Utilizing elephant labor also helps protect forest health. “Extracting logs from the forest with elephants has the least impact on the environment,” says Soe Min Oo, “because the elephants know the forest and know how to get the log out without damaging the forest.”

Elsewhere in the world, loggers use small bulldozers to clear pathways through the forest — called skid trails — to each and every tree they extract. This network of trails, often poorly planned, is responsible for part of the forest loss associated with selective logging.

But elephants can skid the logs through the forest without this extra damage, limiting roadbuilding to only the tracks needed to reach central log piles. “Working elephants make a major contribution to minimizing the impacts of road construction,” says Tint Lwin Thaung. Under British management the system was even more sustainable: Bulldozers weren’t an option, so the elephants dragged the teak trunks to the dry streambeds, where the monsoon rains washed them down to the major rivers.

By destroying additional vegetation, roads and skid trails also increase carbon emissions. “Ongoing research from other geographies shows that skidding represents, on average, about 10 percent of all logging emissions,” says Peter Ellis, a forest carbon scientist at the Conservancy. “So if we assume that using elephants reduces that damage to almost zero, we could probably reduce your logging emissions by close to 10 percent.”

Roads also exacerbate erosion and provide easy access to deep areas of the forest that would otherwise be impenetrable. So even a modest reduction in the number of logging roads has exponential benefits for the forest, which in turn protects the habitats used by wild elephants and other wildlife.

Unemployment Looms for the Timber Elephants

Despite their cultural and economic value, both working elephants and the traditions of mahoutship are at risk from multiple threats. The first is a shortage of work, as the government tries to reform the logging industry to protect Myanmar’s forests from catastrophic overharvesting.

In 2016, the Burmese government implemented a one-year ban on logging operations across the entire country, in order to assess their forest reserves and launch a reform of the Forest Department. The MTE-owned elephants were unaffected; they either rested or worked transporting already-felled logs. But the ~2,500 privately owned elephants were out of work for a full season, creating a financial crisis for their owners.

Without work, the elephants grew restless and unhealthy, while their owners struggled to make ends meet for themselves, their families, and their elephants. A mature elephant can eat as much as 300 pounds of food each day, so without a steady flow of income, caring for one or more elephants quickly becomes a financial burden that most Burmese are unable to bear.

Some owners were able to eke by for a year, but others were forced to sell their elephants to Thailand, where a tourism boom is creating a bottomless demand for captive elephants. “The elephants and their owners are so attached to one another,” says Tint Lwin Thaung. “It’s heartbreaking if they have to sell their elephants … it’s like selling your own daughters and sons to someone else.”

The unregulated industry is rife with animal abuse and relies heavily on mahouts who flee Myanmar because of ethnic conflict and violence. With no legal status, these mahouts work in dangerous conditions for tour operators who don’t respect their expertise or understand elephant care. Deaths do occur, for both mahouts and tourists.

Even though the government lifted the temporary logging ban in most areas, some private owners still struggle to find regular work, as logging operations move around the country year to year. And Tint Lwin Thaung says that more and more operators are switching over to fully mechanized extraction so that they can log faster. “Elephants are cheaper, but not they’re not economical,” says Tint Lwin Thaung. “They work at their own pace and you can’t rush them.”

Protecting Myanmar’s Elephant Legacy

In early 2018, conservation NGOs worked with the Myanmar government to create a conservation strategy for Myanmar’s elephants. But a robust conservation program for the working elephants is still needed to link this strategy with the government’s forestry reform.

Tint Lwin Thaung says an improved registration system for all captive elephants would help the government monitor the wellbeing of both elephants and their mahouts or owners. With more accurate knowledge about the location of each elephant, MTE can better distribute elephants across the country to ensure they have the labor they need and the elephants have steady work. And this system will hopefully help quantify the number of elephants lost to poaching, and identify private owners who are struggling financially, before they’re forced to sell their elephants.

Tint Lwin Thaung also wants better outcomes for elephants once they retire, typically around age 55. “Once they retire, they are supposed to be able to roam around [a care center] and receive food and medical care,” he says, “but the demand for elephants from neighboring countries is too high.”

Part of the problem is financial: both MTE and privately owned elephants earn a pension from the government, but the system isn’t well organized and that money doesn’t always make it to the retirement centers or individual owners. Both the improved registration system and a formal retirement care plan would help address these problems.

Tint Lwin Thaung also hopes that these retirement facilities could help meet the growing demand for elephant tourism with Myanmar in an ethical manner, while also providing work for mahouts and environmental education for both locals and tourists.

Afternoon passed slowly on our last day in the Elephant Camp. As chainsaws buzzed in the distance, I watch a young male wander through the clearing, stopping to sniff a bulldozer parked at the forest’s edge. With care, Myanmar can continue using both mammal and machine to log their forests, to the benefit of both elephants and ecosystem.

All this information is completely wrong. Elephants are intelligent animals that live in complex family structures with deep bonds of love and friendship. These poor working elephants are taken away from their mother and families when babies and have to go through the “crush” in order to become slaves and be exploited by humans the rest of their lives. They endure decades of isolation, illness and horrific abuse. Please, stop sugar coating this extreme cruelty and educate yourself! I can recommend the film “Love & bananas”

Wrong, all wrong. The elephants do not grow restless without work! They’re not supposed to be working for human beings. They were taken off their mothers and tortured relentlessly to do what they do. Please search in YouTube for ‘the crush’ and watch what baby elephants have to do endure during training. This process is designed to crush them spiritually and physically. I’ve never seen anything so distressing in my life.

Wonderful; keep helping with the problem.

These intelligent social, loving Elephants should not still be logging in any of these countries in Asia. They are chained up when not working, and then they have to endure long hours of pulling and pushing extremely heavy trees. They should and need to be FREED from this ENSLAVEMENT and CAPTIVITY.

Thanks, great story. I like to see the elephants being used for good, and not being slaughtered for their tusks. Myanmar is their Union, and trying to take care of these elephants with good hours and restrictions, to help protect them and with NC’s guidance, improve.

I am a supporter of The Nature Conservancy and appreciate the many ways in which the organization works with locals to find solutions to environmental problems around the globe. But I must take exception to the strategy of exploiting elephants, forcing them to haul 1 ton logs 5 to 8 hours per day, 5 days per week, until they are 55 years old…. then have to work in “elephant tourism”?

I’d like to know how these elephants are trained. I have seen videos of the brutality inflicted upon young elephants to “break” them, and subject them to the will of their human slave-bosses. The pictures accompanying this article show very heavy chains on the elephants. And bark harnesses? Seriously, how comfortable can that be?

Elephants are magnificent creatures, highly intelligent, family-oriented, and emotional. They are meant to be living free, not working as slaves for humans until the day they die. Myanmar needs to find a better way to sustainably harvest their forests. I am deeply disappointed in you, Nature Conservancy.

What a wonderful lesson! I had no idea this was happening and thought all elephants used to haul lumber were treated poorly and often cruelly. I am so glad to learn that this is not necessarily the case.

If I could relive my adult years I would consider such a worthwhile life emulating someone like Justine!

Thank you for this information!