What does conservation have to learn from electrical engineering? That was the unlikely question that Brad McRae answered when he switched careers from electrical engineering to conservation. Brad’s insight into the similarities between how electrons move across a circuit board and how species move across landscapes has influenced the thinking and practice of conservationists around the world. Brad was a senior landscape ecologist for The Nature Conservancy’s North America Region when he died on July 13th, 2017, after a brief battle with stomach cancer. He is survived by his wife, Theresa Nogeire McRae, also a conservation biologist, and their two children.

Brad earned a bachelor’s degree in electrical and computer engineering from Clarkson University in 1989 and went to work as an electrical engineer with National Cash Register in Ithaca, NY. Four years later, he switched careers and earned a Masters in wildlife ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He then spent a couple of years working for the Okanagen-Wenatchee National Forest before starting a PhD program at Northern Arizona University in 1998.

For his PhD, Brad worked on the landscape genetics of pumas (Puma concolor). At the time, the primary tool for understanding animal movement plotted the “least-cost path” between habitat patches. However, least-cost path analysis is not well suited to estimating gene flow between populations. Using insights from his previous career as an electrical engineer, Brad intuited that gene flow across a complex landscape should follow the same rules as electrical conductance in a complex circuit with many resistors. Electricity flows from source to ground via all possible paths, not just along the single path of least resistance. Calculating the net resistance from source to ground can be done with simple equations (Kirchhoff’s Laws). Thus, the concept of modeling species movement using circuit theory was born.

While the concept of circuit theory is intuitive, it is also supported by a rigorous mathematical foundation—a foundation that Brad developed. He demonstrated that the existing dominant paradigm of “isolation by distance” could be considered a special case of his broader theory of “isolation by resistance.” More importantly, it turns out that Brad’s circuit theory could predict patterns of gene flow for plants and animals inhabiting real landscapes better than traditional connectivity models.

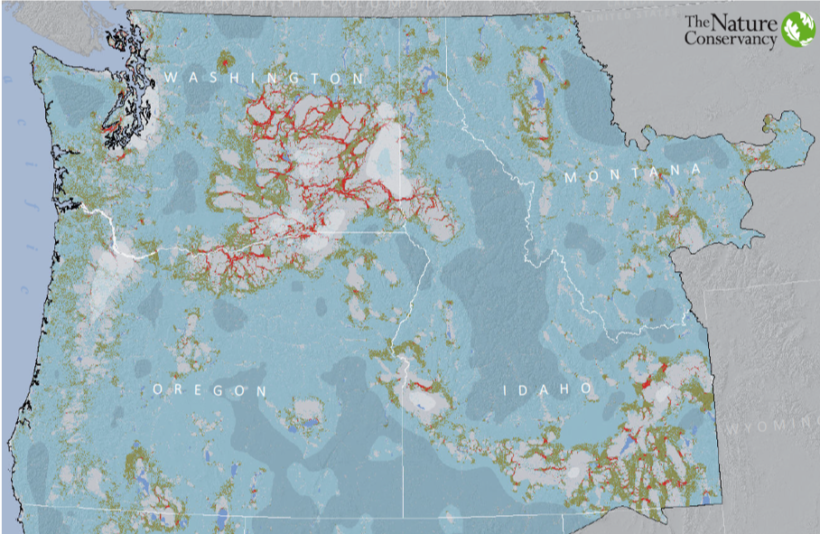

Brad wanted to see his insights have real-world applications to benefit conservation. To realize this dream, he worked with Viral Shah and others to build Circuitscape, a freely accessible, open source software to model and map connectivity. Circuitscape’s latest release has been downloaded more than 25,000 times and has been used in at least 274 peer-reviewed studies. Brad’s software has found impressively broad application. It has been used broadly in conservation, including exploring how species will move in response to climate change. But it has also been used to predict the spread of fire and where to put fire breaks, to identify where diseases originated and how they spread, to model hydraulic resistance in root systems, to retrace the steps of early explorers, and to model whether early modern humans left the African continent in one or more waves.

More importantly, from a conservation practitioner’s standpoint, his work has been integrated into local and regional conservation-planning efforts around the world – literally on every continent (i.e. including Antarctica). The results of these analyses are not only being used by The Nature Conservancy, but also by land trusts, governments, and foundations.

This broad impact was not just due to Brad’s brilliance as a scientist. It was also due to his deep commitment to conserving nature, and his tremendous generosity with time and ideas which led him to share his expertise with colleagues around the world interested in applying his tools. He spent countless hours working with collaborators, mentoring graduate students, providing analytical and ecological advice—helping with distant projects that he would likely never see. All that knew him remember his kindness in these interactions; those that knew him best remember his great sense of humor, love of pranks, and fondness for ice cream and chocolate.

Brad likely came to a career in conservation through his love of the outdoors. He had a true love of backcountry and downhill skiing, mountain biking, paddle-boarding, and other water sports. Bird watching and botanizing were typically part of these outdoor adventures. Most importantly, he was a caring husband, father, and friend — as well as a dedicated conservationist.

Brad’s insights and ideas live on and continue to benefit conservation, even as he is deeply missed by those who had the privilege to know and work with him.

Brad’s colleagues at The Nature Conservancy, along with Circuitscape co-developer Viral Shah and several other collaborators are continuing to develop and update the tools he pioneered. Check the Circuitscape website or GitHub development site for new information and software releases. Also, an “Innovation in Conservation” Fellowship has been established by his family and friends at Northern Arizona University.

Where Can I download 64-bit Windows executable?

I want to use linkage mapper to run pinchpoint in ArcMap but circuitscape is not installed in my PC.

I tried to install via julia terminal but still pinchpoint tool never work