“Netting a bat in an open area is like finding a needle in a haystack,” says Lance Risley, professor of Biology at William Paterson University in New Jersey.

I’m sitting in a circle of camping chairs and bat research equipment with Risley and his students, the full moon shining above us. To the casual observer it might look like we’re camping – until their eyes adjust to the dark and they see the mist nets, strikingly similar to volleyball nets, standing several feet away.

Risley and his team are at The Nature Conservancy’s High Mountain Park Preserve in New Jersey hoping to catch a northern long-eared bat, a once abundant species now federally threatened in the US and proposed to list as endangered in New Jersey because populations have been decimated by White-Nose Syndrome (WNS).

The experience is not unlike camping with friends. We chat about the best snacks and equipment, but the focus is on things like glow-in-the-dark headlamps, solar-powered flashlights, the perfect thickness of leather gloves – the little things that bat researchers need in the field. Our artificial light sources are limited and we speak in hushed tones (light and noise could disturb the bats).

Every ten minutes a student sets out quietly to check the mist nets. They keep their flashlights to the ground until they reach the net and then quickly scan for “blobs” — those are the bats in the net. It’s important to check frequently; most bats can escape by chewing through the mist net in about ten minutes.

The chances of catching our target species on any given night are low, but each bat caught provides important data for researchers and conservationists working to protect the species, so we wait.

Recording the Sound of Silence

Bat researchers have two primary ways of gathering data – capturing individual bats in mist nets to learn more about them and, a more passive option, setting out acoustic recorders to capture ambient bat calls in the area.

In the 2016 field season Risley and his students netted two northern long-eared bats on High Mountain Preserve, and preliminary acoustic data for the 2017 field season is promising. Given the rarity of the northern long-eared bat in the state even small numbers of bats are an important source of data.

Most bat echolocation calls are inaudible to the human ear, but technology allows researchers to capture the sounds and transform them into sonograms or translated into sounds within the audible human range. Recent advances include ultrasonic apps and attachments for your smart phone.

On the day before mist netting, I went out with Jennifer Ghahari, an adjunct professor of sociology who is working with Risley on the bat study, and Jim Wright, a trustee of the Nature Conservancy in New Jersey, to retrieve the acoustic data. We set out with vague instructions to look near a fallen log in the stream (I saw at least ten fallen logs). After retracing our steps a few times, we came upon a tall microphone next to a tree, but this microphone was not there for an entmoot, it had been capturing the sounds of bats all night.

Near the microphone next to the tree there was an unassuming box that looked like a battery – this held the acoustic monitoring device that records data captured by the microphone.

As she took down the equipment, carefully measuring and recording the height and direction of the microphone as she did so, Ghahari explained that they keep the recorder in the box partly to protect it from weather and partly to protect it from people who might otherwise think that it is a camera and try to take it apart (people, understandably at times, don’t like being monitored).

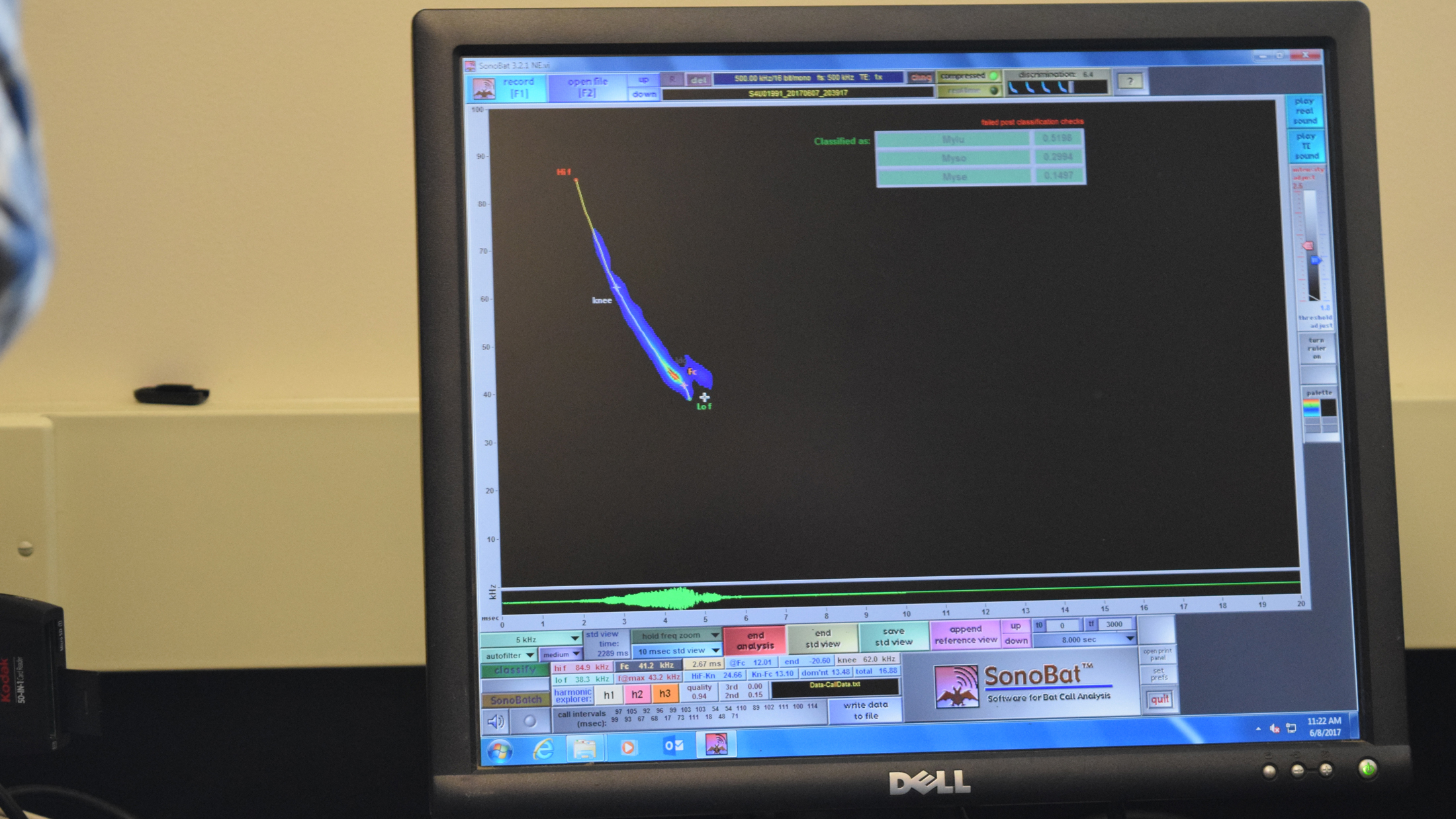

Back at Risley’s lab we plugged the monitor into his computer and it quickly converted the data into visual representations of sound. Monitors pick up everything within a set range — in this case everything from jingling keys to insects to flying squirrels to bats that produce ultrasonic sounds. Fortunately the computer helps sort out the bats from other data — katydids are so common and make such constant noise that there is an “anti-katydid” button built just for them — and we soon saw bat calls.

The computer software suggests possible species, but bat calls are similar enough that its recommendations are most reliable at the genus level. The northern long-eared bat, for instance, has a call that can be confused with a close cousin, the little brown bat.

Within minutes of searching, we found a call that Risley confidently identified (based on the appearance of the sonogram as well as the habitat it was recorded in) as a northern long-eared bat — they’re still out there.

Hope for a Dwindling Species

The northern long-eared bat would fit easily into the palm of your hand, averaging only 3 inches long and weighing in at about 6-9 grams. Only their 10-inch wingspan can make them appear relatively large.

Their bodies are covered in fur and they have oversized, Yoda-like ears. In addition to their wings, they have a membranous tail-flap that they use like a scoop to snatch up their insect prey – an impressive feat in mid-air.

The northern long-eared bat, which was never as abundant as the little brown bat, has been among the species hardest hit by WNS.

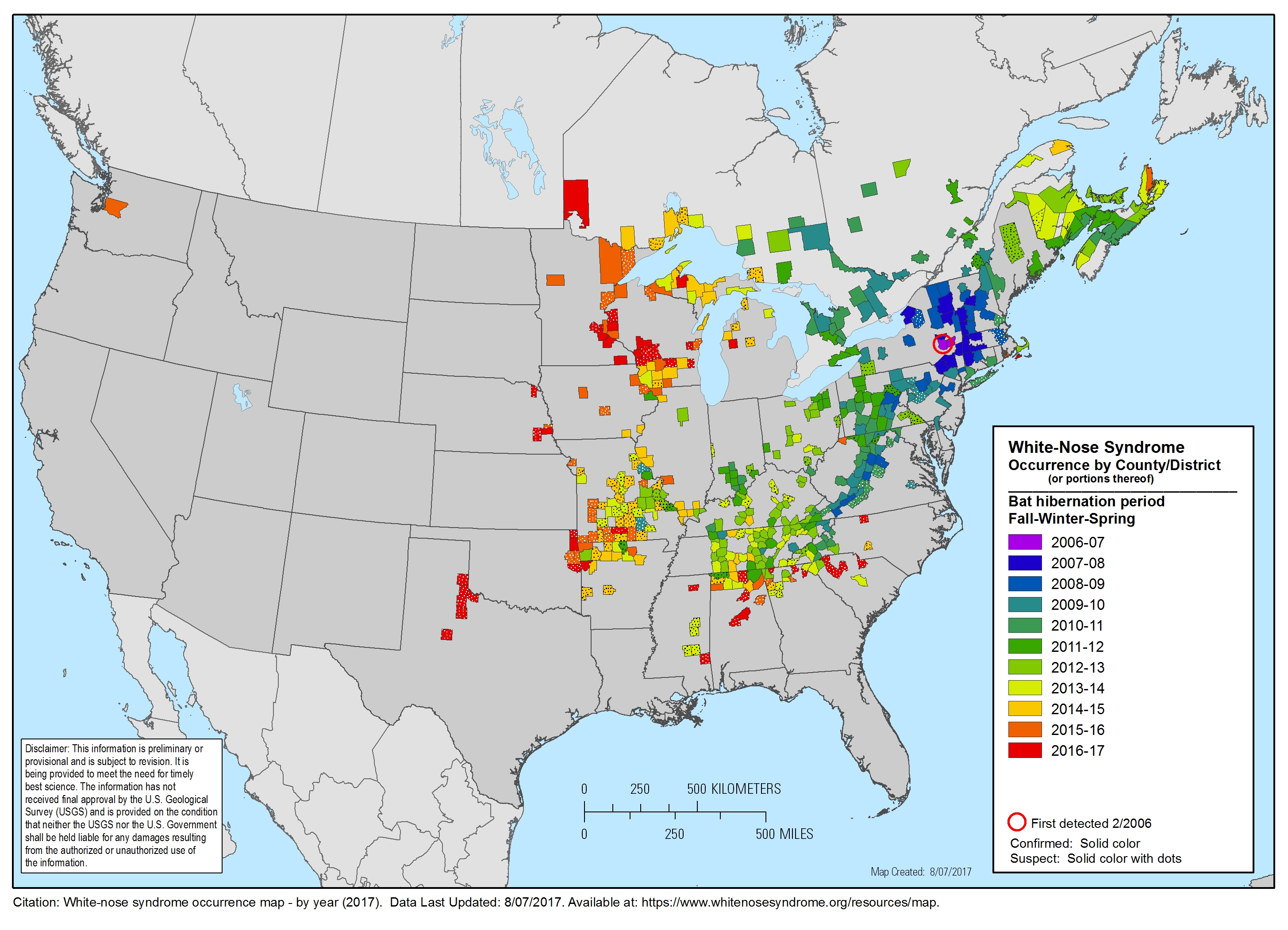

The story of the spread of WNS has become one of conservation’s horror stories. It was discovered in New Jersey in 2009. Risley recalls that you could tell by that summer that there were fewer bats being caught in mist nets, and a lot of those caught had wing damage (a characteristic symptom of the disease).

An example of the disease’s power: the largest known hibernaculum in New Jersey used to host an estimated 30,000 bats of various species (a small proportion of them northern long-eared bats) prior to the discovery of WNS. After WNS, that number plummeted to 300-400 total bats. It’s possible that not all of those bats died; Risley points out that some may have moved to a different cave, but thus far no similar large aggregations have been found.

In the case of the northern long-eared bat, numbers have dropped by an estimated 98% in New Jersey. Where Risley once caught 25 bats in a summer, he would now be lucky to catch 3 or 4. In the summer of 2017, only one long-eared bat has been caught in mist nets by scientists in the entire state of New Jersey, despite an intensive mist netting and telemetry program.

When researchers do find northern long-eared bats, they carefully collect data on the location, the conditions, and the health of the bats. Though we weren’t fortunate enough to see a northern long-eared bat on my night out with the researchers, I was able to witness part of the process with two big brown bats (which are actually surprisingly small, but get their name from being larger than other similar species).

The Night of the Mist-Netting

Once the mist nets were set up, the team recorded the moon phase, wind speed and direction, the temperature, and GPS coordinates, and made a diagram of the area showing the relation of the mist nets to the stream and trees.

When a bat was caught in the net, everyone came over to watch Risley very carefully disentangle the bat from the net in a process that looked not entirely unlike disentangling a birdie from a badminton net — if the birdie were struggling and you had to be careful not to injure it.

Each bat then went into a clean bag for its own safety, with bags numbered and recorded so that none would be reused. Anyone who handled a bat wiped down their gloves afterward with disinfectant — two of the many precautions in place to prevent the spread of WNS.

Then the researchers weighed the bat and measured its forearm length to the millimeter with calipers. Risley carefully palpated the abdomen of each bat to check reproductive stage & health — one male, one pregnant female.

Risley then pulled out what looked like a friendship bracelet, but it was actually a series of tiny tags on a string, he gently crimped a tag over her forearm. These tags are exceptionally light and are placed such that they do not hinder the bat’s flight. Each tag is labeled with the letters NJ DFW (New Jersey Division of Fish & Wildlife) and is uniquely numbered so that the individual bat can be recognized – each state has its own letters and numbers. They provide invaluable data as recaptured bats can be identified and their health, reproduction, and survival tracked over time.

Next, the team checked for WNS by backlighting her wings with a flashlight to search for any damage — this bat looked healthy — and then scanned underneath her wings for parasites — she had some mites, which is not uncommon for female bats in the Myotis (such as northern long-eared & little brown) and Eptesicus (such as big brown) genera since they roost communally in “maternity colonies.”

The entire process is repeated for the second big brown bat (a male) who also gets a clean bill of health. Big brown bats are not as threatened by WNS. Though they can get the disease, more of them are able to recover from it.

Once the measurements have been taken, the bats are released. The female lingers in a student’s hand until she is gently nudged, finally she flies away. The male, eager to take flight, climbs a student’s arm to get a better vantage point for take-off.

Had a northern long-eared bat appeared in the mist net, especially if it were a female, the researchers would also have glued a small radio transmitter to her. The glue wears out and the transmitter falls off within a couple of weeks – the battery has a lifetime of 12-14 days. The day after the transmitter is attached, scientists set out with radio telemetry equipment to track the bat.

If it is a female, they hope to track her to a maternity roost where they will set up mist nets; count, tag, and record data for all of the bats; and note the tree species and location. About 10-30 northern long-eared bats might share a maternity roost — a treasure trove of information for scientists. Males, though often solitary, are also tracked so that researchers can learn about their habitat preferences.

Northern long-eared bats reproduce slowly, giving birth to only one pup a year, so it will take time for populations to recover from such a hefty loss. Protecting the areas where they are known to roost and hunt and learning more about them so that other similar areas can be found and protected can gives the bats a better chance to recover.

WNS continues to spread across the country, decimating populations as it goes. It is not yet known whether bats that survive can become immune to the disease, though there is some preliminary evidence that they can be treated. Most efforts are directed at slowing or preventing the spread of WNS and protecting the bats that survive.

A Slice of Bat Paradise?

“This location is a special place,” Risley says, “This pool of water stays, even in hot dry conditions. That’s rare – there’s always drinking water for bats.”

High Mountain, now a preserve owned by The Nature Conservancy, the state of New Jersey, and Wayne Township, has a rich history that is almost literally unbelievable. Before European settlement, Franklin Clove was home to the Lenni Lenape people — as far as ten thousand years ago its cliffs were inhabited by their ancestors who made lean-to structures against overhanging rocks. There are rumors that during the American Revolution George Washington’s soldiers used High Mountain to watch the movements of British ships in New York harbor — skyscrapers now block the view of the water, but the view of New York City lends credence to this tale.

The preserve wasn’t protected for bats, however, and it wasn’t protected for history, it was protected for a rare plant called Torrey’s mountain mint. The plant still survives in the preserve and has now become an unexpected “umbrella species” of sorts, protecting bats that nobody had foreseen would be threatened.

Despite the proximity to New York City, here the bats have a patch of forest habitat to roost in, insects to eat, and slow-moving water to drink — the slow movement is important because the sound of rushing water can interfere with echolocation calls.

High Mountain is about 1,260 acres – not very large for a forest and not connected to other protected areas – and yet it is enough to protect so much diversity and history.

They’re Out There

Acoustic data for the 2017 field season picked up northern long-eared bat calls on four of seven nights in four different locations in the preserve. While it’s possible that it was the same bat flying around the preserve, Risley says the multiple locations indicate it is more likely that there are multiple bats at High Mountain.

They might also be hanging out in unexpected places – some have been found hibernating in the crawl space under people’s houses. If you find bats in your crawl space or attic, don’t panic, the best way to remove a colony from your home is to exclude them. Find out where they entered, wait for them to leave, and then completely seal the entrance and clean up any droppings that are left behind. The bats will find a new home, and your home will be easier to clean.

Slices of bat paradise, like the one at High Mountain and others yet to be found, give bats room to reproduce and recover. While I was disappointed we didn’t get to see a northern long-eared bat on my night out with the researchers, as Risley says, “they’re out there.”

So interesting. Thank you!