The quest to restore the American elm has been underway for more than half a century. Today, with help from The Nature Conservancy’s Christian Marks, success is closer than ever—which is good news for our floodplain forests, as well as our urban communities.

On a humid day in mid-June, Jessica Colby is hunched over a collection of bright green stems, each one waving a leaf or two, each one a tiny banner of hope. It’s almost noon, and the temperatures in the greenhouses at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst are climbing. Colby pushes her hair off her damp brow and, wielding a small blade, gently scrapes the outer layer from the stem she is holding, before dipping it in rooting powder and adding it to the lineup of cuttings anchored before her in a moistened block of foam. The leafy stems march in straight rows across the table, like a band of miniature soldiers fighting for a cause.

Colby and her fellow interns, Izzy Bazluke and Lisette Stone, are, in fact, the latest recruits in what has been a long battle to bring back one of America’s most iconic trees, Ulmus americana. Their fearless leader, Christian Marks, a floodplain ecologist with The Nature Conservancy’s Connecticut River Program, has spent more than a decade tackling floodplain restoration in the Northeast, with a special focus on the American elm. Along the way, he’s developed an eye for what he calls survivor trees—like the two on Elwell Island in Northampton, Massachusetts, where Colby’s stems were harvested. “It’s sort of an obsession with me now,” he says. “I’m always watching, always looking.” As he drives New England’s winding roads, Marks peers into the forests, past the shadows, looking for the elm’s distinctive vase-shaped form, rising above the canopy. These massive trees—often 100 feet tall and more than 100 years old—stand alone in the forest now, surrounded by smaller dead and dying elms, reminders of another time.

Loss of an Icon

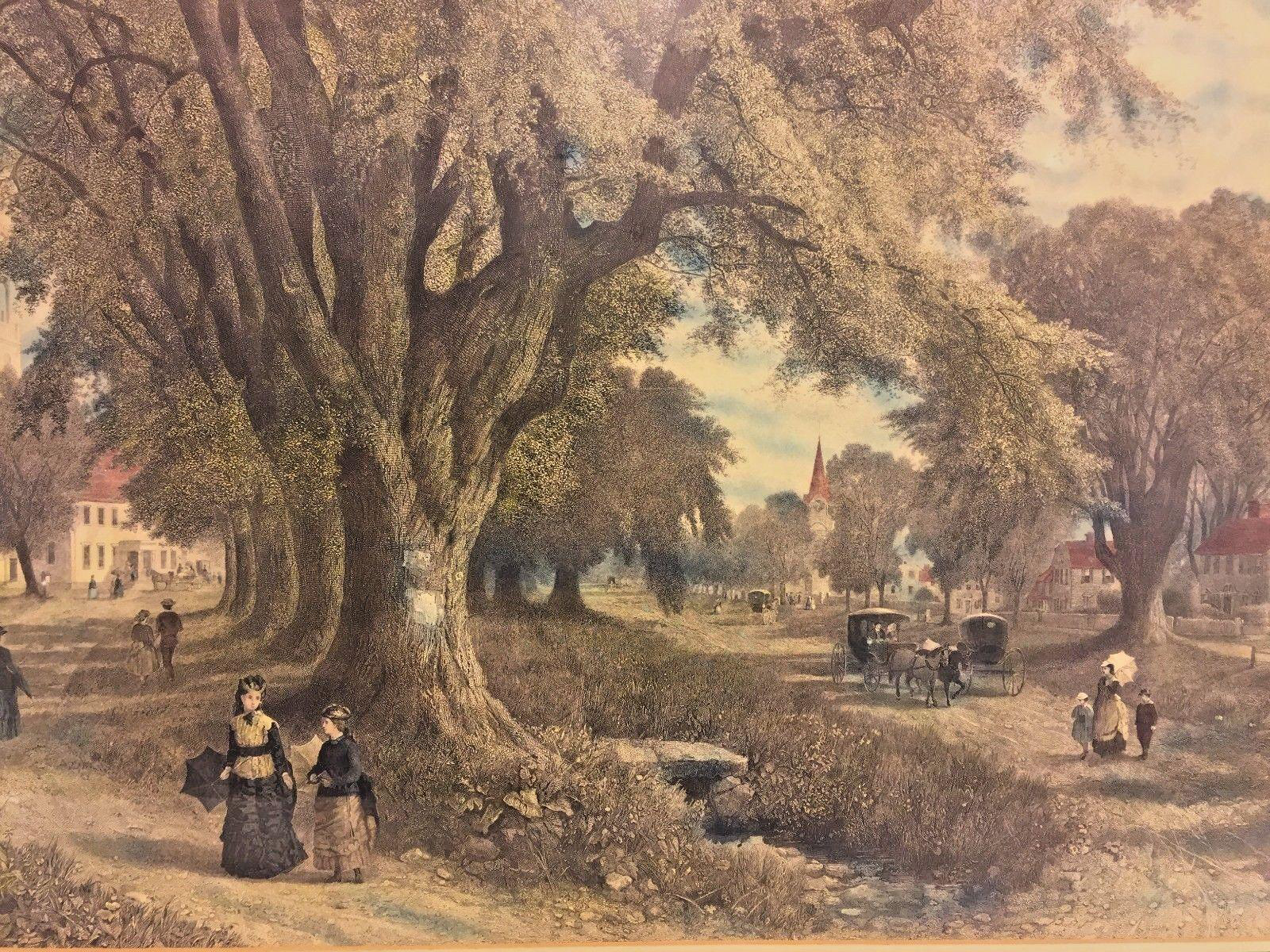

The tragedy that befell one of the country’s most magnificent trees began nearly a century ago. First described in the Netherlands in 1919, the Dutch elm fungus is carried by the European elm bark beetle, which crossed the Atlantic in 1930 in a shipment of logs purchased by an Ohio furniture maker. Before long, Dutch elm disease (Ophiostoma ulmi) was sweeping across much of the eastern United States. One after another, the giant trees were infected—and then swiftly cut down. Their famously arched silhouettes, which once soared in shady cathedrals of intertwining branches along countless community main streets, vanished, leaving behind barren stretches of pavement and neighborhoods stripped of beloved trees that had stood for generations. By the 1980s, millions of elms had been lost. The devastation continued along the region’s riverbanks, where the elm had been an anchor species in the floodplain forests, providing critical habitat for wildlife and protecting human communities from rising waters during severe storms.

Today, most of us have never stood beneath one of these iconic trees. Perhaps our grandparents remember them. Or maybe we’ve visited New York’s Central Park or the National Mall in Washington, DC, where fungicide treatments and generous endowments have helped to preserve a few remaining noble specimens. But for most of us, the giant elm is the stuff of legend, a lost wonder of the natural world. And while young elms persist along our riverbanks, almost none survive long enough to reach the canopy. The ancient tree has vanished from the forest, too.

If Marks has his way, though, the legend will live again. Elms along our riverbanks will help to save an entire ecosystem of expansive floodplain forests, and generations to come will experience once more the profound beauty of these soaring trees along our city streets. But restoring a legend, it turns out, is not for the faint of heart. The process is labor intensive and fraught with uncertainty, demanding years of strict adherence to careful scientific methods—and endless reserves of patience. Success, ultimately, requires a leap of faith, an understanding that today’s efforts are a gift to the future, to forests unseen.

Labor of Love

In the sweltering greenhouses, interns Colby and Bazluke methodically complete row after row of cuttings—about 270 by the end of the day. “We thought the whole propagation process would take about a week,” says Stone, who has overseen the painstaking effort. “But it took four.” In the end, the three interns, with help from a band of volunteers, completed 4,827 cuttings. Only 25 percent were expected to take root. But three weeks later, more than 90 percent had successfully rooted, defying expectations. “It was a great problem to have!” says Stone, who then worked nearly round the clock to get all the rooted cuttings potted. Those that survive, will eventually be transplanted into trial plots, where they will be tested for disease-resistance.

This is the secret to successful restoration, explains Marks. “We need new varieties—genetic diversity.” For more than 60 years, researchers have been scrambling to develop this diversity, searching for varieties that can withstand Dutch elm disease, including a second more virulent form of the pathogen (O. nova-ulmi). “We now have seven varieties that demonstrate good tolerance,” says Marks. Two of these, Princeton and Valley Forge, were successful enough that they are now sold in nurseries and are slowly being reintroduced into the urban landscape. “But seven varieties is not enough,” says Marks. “We need to double that number for long-term survival in the wild.”

Jim Slavicek is a research biologist at the USDA Forest Service’s lab in Delaware, Ohio, where he and his team have been working on elm restoration since 2003. “The DED fungus mutates,” says Slavicek, “which means it will eventually overcome the tolerance that exists in selections like Princeton and Valley Forge. That’s why we need to focus on the forested landscape, where the most DED-tolerant trees can naturally propagate and evolve, eventually developing mechanisms that can withstand future onslaughts of the fungus.” Urban settings, by contrast, typically feature single varieties, and the trees tend not to propagate themselves. Ultimately, restoration of naturally occurring forest elms will provide a source of disease-tolerant trees for use in urban settings, too.

No one knows the ecology of floodplain forests better than Marks, who has spent years pulling on waders and exploring the Connecticut River watershed, often tramping through the forest understory in waist-high water. At nearly every site he’s studied—more than 100 in all, elms are still taking root, but they are quickly succumbing to disease, never reaching the soaring heights of centuries past. “We realized that we have to figure out how to get this species back, if we are truly going to restore these floodplains,” says Kim Lutz, director of the Connecticut River Program. And so began a partnership. The Forest Service had the facilities, skills, and staffing to do the meticulous breeding needed to establish new varieties. The Conservancy had land where new trees could be planted. And they had Christian Marks, with his intimate knowledge of New England floodplains and the region’s great survivor trees.

“Rainbow. Podunk River. Hadley. Whale Tails. Cummingham. Goff Brook—I’ve collected from all of them,” says Marks, reeling off the names of some of the ancient elms he has stood beneath each spring, watching as arborists climb 60 or 80 feet up into the spreading limbs. The clipped branches spiral to the ground, where Marks waits to collect and label them. Of the 50 survivor elms Marks has worked with in New England, only about one in four will have elevated tolerance for the disease. His tireless mission, year after year, has been to figure out which ones might hold the promise of new hope for the American elm.

Some of the branches he collects provide the cuttings to make the clonal copies started by interns at work in the greenhouse. Others are rushed overnight to the US Forest Service research station in Ohio, for the start of the complex cross-breeding process. Here, they are recut and stored in water until the flowers open and drop their pollen onto the wax paper below. Next, USFS researchers collect the pollen and head out to the trial plots, where varieties of disease-resistant “mother” elms, including Princeton and Valley Forge, have been planted. Here, the fresh pollen from the ancient survivor “father” trees is carefully blown onto individual branches, each one encased and sealed in a plastic bag so as not to be contaminated by stray pollen from other trees. “Every father tree is crossed with at least two mothers,” says Marks. “We have more than 100 crosses at this point.”

A couple of months later, the USFS team collects the seeds produced by the latest cross and rushes them back to Marks in New England, where they are planted in tiny pots—and carefully labeled. Row after row of seedlings line the tables now at the UMass greenhouses, some no bigger than a fingernail, others nearing three feet in height—about 800 in all. With help from her team, Stone checks their progress every day, noting signs of growth invisible to the casual observer. For months, the whole batch of tiny seedlings, along with the thousands of cuttings, will be carefully tended and repotted, before they are ready for transplanting to test plots in the field. Then comes the waiting and watching.

For the next several years, at sites in Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Massachusetts, Conservancy interns will monitor the progress of the fragile elms. This summer, Colby and Bazluke spend long days in the field hacking their way through thick vegetation to reach the saplings, battling tall grasses, giant ostrich ferns, and tangles of thistle, bindweed, and stinging nettle. They measure basal diameter and height. They look for tags, making sure each tree is labeled. They spray deer repellent and check to be sure every trunk is wrapped for protection from rodents. They slash away at any competing weeds. And they keep an eye out for yellow and wilting leaves—signs of DED.

“It’s pretty wild to see all these little trees planted out there,” says Gus Goodwin, conservation coordinator for The Nature Conservancy’s Vermont chapter. “And to realize how long it will be before we’ll have any definitive answers about survival rates. But it’s a great feeling to be part of this process.” Goodwin, who is also a woodworker with an appreciation for the unique characteristics of elm wood, adapted an existing app that has dramatically improved the quality and efficiency of the field work for Marks and his team. “Essentially, it allows elm techs to use a high-accuracy GPS to precisely map where the trees are planted,” he says, “which means less time spent searching for hidden saplings!” The app also makes it easy to enter all the growth, health, and vigor data out in the field, and then synch it with the database back at the lab for speedy editing—a quantum leap from the laborious task of re-entering data from hand-recorded sheets, notes Goodwin. “And then double- and triple-checking every entry for accuracy.”

When the tiny elms reach 1 inch in diameter, the injections begin—every single sapling gets a shot of the two strains of DED. “That is the moment of truth,” says Marks. “We can tell in a couple of weeks whether they will be disease resistant. Most are dead by the end of the summer.” Those that survive—perhaps a third—will continue to grow and put down roots, pioneers in establishing a new population of wild elms.

Urgent Mission

Restoring a lost species requires a certain kind of humility and tenacity. The work is laborious. The failure rate is high. The timeline is long. But Christian Marks is not easily daunted. He has a vision of what’s possible—and he loves these trees. “I’m just lending a helping hand early in the process,” he explains, describing what he likes to call his dating service for elm trees. “Eventually, we will walk away, and the evolution of resistance by natural selection will take over.”

But first, he explains, urgency in his voice, we need to establish enough disease-tolerant trees in the same place so that they can breed among one another. The recent outbreak of a new invasive pest, the emerald ash borer, which is attacking another critical floodplain species, makes the restoration and replanting of elms along rivers in the Northeast more urgent than ever. “The good news,” says Marks, “is that we have several new varieties in the pipeline that look promising. We are nearing the finish line.”

A recent grant from the Manton Foundation is helping to speed the restoration process along, including the flurry of propagating work in the greenhouse this summer. “Thanks to their generosity, we are in the midst of a five-year effort to see if we can double the number of disease-resistant cultivars,” says Lutz.

Progress can’t come soon enough. As the threat of climate change continues to loom, more and more people are beginning to understand why floodplains are so important, why we need these giant protective sponges along our riverbanks to buffer human communities from rising waters. Floodplain forests also filter sediment and excess nutrients to protect water quality, and they provide habitat for wildlife and recreation for people. Urban areas, too, are poised to benefit from the return of the elm, as cities seek green solutions to climate change. Studies have shown, for example, that a single large American elm, located on the southern side of a home, can intercept 2,384 gallons of storm water, conserve 107 kWh of energy, and sequester 518 pounds of CO2 annually.

“No matter where I go,” says Mark Smith, deputy director for The Nature Conservancy’s North America Water program, “the reality of increased floods and flooding damage is front and center.” The issue unites people, he notes, cutting across every geographical boundary and every party line. From the hills of California to the fields of Iowa to the coast of Louisiana to the banks of the Connecticut River in New England, communities everywhere are looking for solutions. “One of Christian’s great contributions to this effort,” says Smith, “has been his deep knowledge of floodplains and their dynamics and what’s needed to bring them back. And, of course, his commitment to the elm.”

Thanks to the help of dedicated interns and volunteers, Marks has planted elms at more than 30 sites in the Connecticut River watershed—3,300 seedlings from crosses at the Conservancy’s field trial plots in Vermont and more than 1,000 cuttings from clonal copies of the seven disease-resistant varieties. If some of this year’s 5,000 new cuttings and crosses are successful, more varieties will be joining the original seven. Enthusiasm among volunteers is high. “There’s something about planting a tree,” says Marks. “It’s meaningful to people. It creates a tangible legacy.”

Some of the restoration sites, like the Conservancy’s Maidstone Bends Preserve on the Upper Connecticut River in Vermont, have been successful, boasting elms that now stand more than 20 feet tall. Other sites have struggled. One was destroyed by fire. At another, dozens of young saplings snapped in two, when rising waters froze during a winter flood. But Marks perseveres.

Several new restoration projects are about to get underway, including two in New Hampshire—one along the Ashuelot River in Swanzey and another along the Connecticut River in Colebrook. In Massachusetts, after five years of collaboration with multiple partners, the Conservancy recently helped protect more than 370 acres of rare floodplain habitat just minutes from the city of Springfield. “The scope of this project is unprecedented,” says Marks, noting that, once the Conservancy’s restoration work on the parcel is complete—roughly 223 acres—the Fannie Stebbins Memorial Wildlife Refuge will be the largest expanse of natural floodplain in the Connecticut River watershed.

The restoration effort on the Stebbins land will feature the planting of thousands of trees, including disease-tolerant elms. With each sapling planted, hope will take root once again. Hope for a future where the American elm once again rises high above the forest canopy along our riverbanks. A future where children once again look up from the sidewalk and marvel at the graceful silhouette of a giant elm, shading the street below with its sheltering branches—its presence a quiet testament to the years of dedication and commitment that powered the quest to restore a beloved tree to the American landscape.

Suki Casanave is a writer for the philanthropy teams in Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

Join the Discussion