Recently, a red knot and I crossed paths three times within a single year – in winter, spring and fall.

We first met on an island in Maranhão, Brazil, where the knot and its flock mates were spending the winter. They came to the beach at every high tide, waiting there until the water receded and it was time to feed again.

Our research team was there to catch the birds to deploy tracking devices and take samples for an avian influenza study.

The red knot and I met again four months later, when it arrived at the Delaware Bay in May.

The knot was on its northbound journey from Brazil to its nesting grounds in the Arctic. It stopped at the bay to refuel on horseshoe crab eggs.

I was there to measure the amount of horseshoe crab eggs available to the birds that year.

The last time I met the red knot, it was deceased.

On the return trip from the Arctic, the knot stopped on an Atlantic Coast barrier island in New Jersey, where it had to compete with people for beach space during peak tourist season in late August.

I found its carcass below a peregrine falcon eyrie of a tall apartment building in the congested resort town of Wildwood. I have a pastime of checking the building’s parking lot to see what prey remains the peregrines have been discarding over the ledge of the building.

These encounters (except perhaps the final one) were not a coincidence. The travels of red knots are predictable. We knew we’d find red knots on that island in Brazil in February, and we knew to expect them on the Delaware Bay in May.

I learned about who this bird was and about our common travels by the “flag” it wore: a band with a sequence of three numbers and letters printed on a small tab. Flag codes can be read by anyone with a spotting scope and some patience.

To look up the code, I consulted bandedbirds.org, a database that contains all the sightings of banded shorebirds submitted by birders and biologists.

It was only then that I realized I’d been shadowing this bird (tagged as “L54”) for the last year. It was originally captured and banded on the Delaware Bay in 2012, and had been seen every year since in both Brazil and the bay.

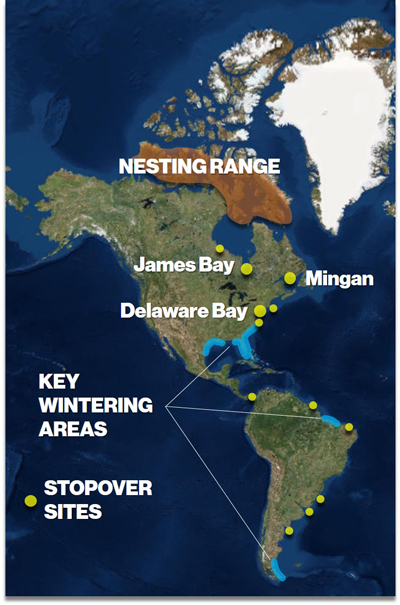

We often tout the vast distances that red knots and other migratory birds cover each year to complete their life cycle. Many red knots truly travel from one end of the earth to the other.

But it’s also true that these birds live in a small world. They are using a relatively small fraction of real estate, albeit spread across a very large area.

For red knots, much of that vastness is just scenery passing by, like the many miles of our interstate roads that we use to travel from one place to another.

On another trip to Brazil this past winter, I was reminded again of the uncannily small world of shorebirds.

On the same Brazilian beach where we saw L54 two winters in a row, we made a catch of 175 red knots. Out this flock, 20 birds had already been captured and banded, in Brazil and elsewhere.

The history of some of these red knots went back as far as 2008. Some had been sighted as many as 40 times.

Beyond Brazil, they were seen and captured in the Delaware Bay in New Jersey and Delaware, James Bay in Ontario and on a group of small islands called the Mingan Archipelago in Quebec.

The records tell us much about the bird’s travels, but they also are a reminder that there are people at each of these sites every year whose lives intentionally intersect with those of red knots.

The people are there to take the pulse of the population and be on alert for emerging conservation threats.

In the early 2000s, this monitoring system revealed that the sudden declines of red knots were linked to the overharvest of horseshoe crabs in the Delaware Bay.

The loss of horseshoe crabs meant a decline in horseshoe crab eggs available for red knots and several other species of shorebirds to eat during their migratory pitstop in the bay.

Since then, the horseshoe crab harvest has come under better management oversight. Crab and red knot populations have stabilized, but have not yet recovered.

The red knot subspecies (rufa) that primarily uses the Delaware Bay was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 2015.

Shorebird population monitoring in Asia and Australia is now revealing a conservation crisis for red knots and other shorebirds that stopover at China’s Yellow Sea .

Like the Delaware Bay, the Yellow Sea is critical refueling station for shorebirds making the long journey to the Arctic from Australian wintering sites.

The red knots there are in a different migratory lane, representing two different subspecies (piersmai and rogersi).

The loss of habitat in the Yellow Sea is driving steep population declines of red knots and six other shorebird species that depend on the region as a migratory stopover.

The Yellow Sea and Delaware Bay examples illustrate that to clearly identify threats to bird populations, we first need to know where and when to expect the birds to stop in different parts of the world.

For most species, arriving at this knowledge is not a trivial matter.

Shorebirds such as red knots have been among the easier species to establish patterns of “migratory connectivity.”

This is because they tend to concentrate in large groups and use relatively few places across the huge span of the globe.

They also conveniently stand out in the open and are easy to see and count.

For other types of birds, such as small forest songbirds, a clear understanding of migratory routes and linkages between sites has been more difficult to achieve. They are widely dispersed and more difficult to observe. But use of techniques involving isotopes, genetics and tiny tracking tags is getting us there.

It is exciting that we’ve overcome tremendous technical obstacles to track these small birds. But in the wake of these advances comes the sobering responsibility of working to solve the problems that the new knowledge reveals.

Results are showing, for example, that deforestation in central America is linked to regional declines in singing wood thrush. The declines vary regionally because wood thrush nesting in different parts of the United States are wintering in different parts of Central America. The more deforestation in the region where the birds are wintering, the steeper the decline.

This means that the amount of wood thrush song you hear in your local woods depends on how much tree cutting is happening in the particular region of Central America where your birds are wintering.

To conserve migratory birds, we need to address big, complex problems that are often far from home.

But halting deforestation in the tropics and prevailing on the Chinese government to stop destroying tidal wetlands are not easy goals.

How can each of us help with such big problems?

First, we can help to solve smaller problems that birds face by changing our habits at home. See this “10 Things You Can Do For Birds” list for some suggestions.

Second, we can remain aware that the migratory birds we see in our neighborhood have complex lives, facing many challenges in their travels.

Our field guides almost encourage us to consider birds in isolation, presenting each species as a painting on a clean white page.

But our ever-growing knowledge of migratory connectivity can help us make the connection between our local bird habitats with the rest of the world.

A great supplement to your field guide that details some of these connections and provides a primer on a broad range of conservation issues is the American Bird Conservancy’s Guide to Bird Conservation.

It illustrates that caring about birds means caring about environmental issues both at home and across a very big world.

What beach in Brazil can you find the Red Knots at?

This is a great article. The maps are great. I didn’t know about the situation in the Yellow Sea. I’ve traveled in Korea and China, but never realized similar birds were there. When I taught second-graders years ago, I assigned a spring science fair project on migratory birds that stopped in Cape May County. The kids had to choose one bird and describe its journey. Residents here need to realize what a natural resource this bit of land is. Thanks, Joe.

Joe, GREAT article, touching on so many important issues facing the birds. I too, loved tracking the whereabouts of individual birds as I wrote about red knots and horseshoe crabs in The Narrow Edge.

A beautiful article about amazing birds.