Birds and other wildlife are well equipped to deal with cold and snow, as I’ve written in a previous blog. But extremely frigid temperatures and blizzards can tax even hardy wild survivors.

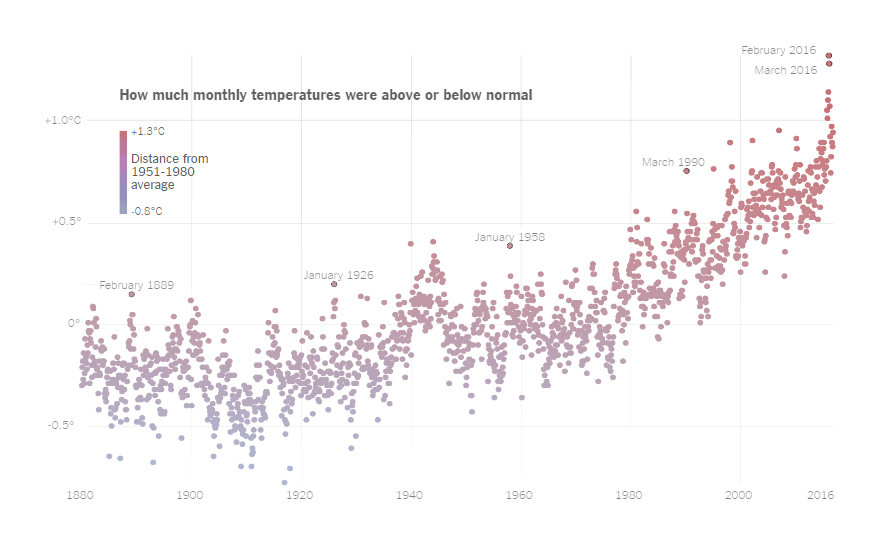

For the third year in a row now, we’ve experienced the warmest year on earth during modern times. But that doesn’t mean we don’t still have blizzards.

To see the effects that extreme winters can have on birds, let’s look back to the winters spanning 1976-1978, when record-breaking low temperatures and legendary blizzards disrupted the lives of people and wildlife.

In January 1978, a blizzard dubbed the “White Hurricane” hit the Ohio Valley, dropping 3 feet of snow and killing 71 people. The following month, another severe blizzard arrived on the east coast that broke snowfall records, was responsible for another 100 deaths and caused almost two billion dollars in property damage.

In 1977, it snowed for the first time ever in Miami and citrus crops experienced widespread damage. The Ohio river froze from Louisville to Pittsburgh. It was the record coldest month across 69 different weather stations in the Midwest and East Coast.

While people grappled with power and gas outages and a limited ability to travel, birds and other wildlife had their own challenges.

While people grappled with power and gas outages and a limited ability to travel, birds and other wildlife had their own challenges.

It must be pointed out that native wildlife are much more resilient to cold than we are. Unlike humans, they evolved in North America and are equipped with the behaviors and adaptations needed to deal with temperate weather. They can migrate, hibernate, or simply eke out a living amidst dormant fields and forests.

That being said, all animals have their limits.

Those species that had the capacity to move away from the cold did so. For example, winter surveys of communal grackle and blackbird roosts in Kentucky found that the counts dropped by 75% during the winter of 1977-78. It’s not entirely clear whether these birds perished or moved further south, but the authors of the study made the hopeful conclusion that the birds escaped to warmer climates.

The deep freeze of January 1977 created an accidental experiment at the southern Illinois where there was an ongoing winter bird survey. During this month, the average temperature was 15°F with the lowest temperature plunging to -18°F. The researchers surveyed forest birds ahead of the cold snap and got out again to repeat the surveys in February after the weather warmed up a bit.

The results were shocking.

After the cold spell, there was a total disappearance of Carolina wren, bluebird, hermit thrush and both ruby-crowned and golden-crowned kinglets. There was a decrease of at least 80% of brown thrasher, winter wren, eastern towhee and junco abundance and declines in numerous other species, including northern flicker and red-bellied woodpecker.

In this case, the authors believed that many of the missing birds perished in the cold and snow. Once they resumed their surveys after the worst of the cold passed, they confirmed this belief, finding numerous dead birds comprising 20 species.

If not for this one accidental study, the plight of these songbirds would have remained undiscovered.

In coastal New Jersey, on the other hand, the birds made their problems obvious.

New Jersey’s salt marshes are the core winter range for both American black duck and Atlantic brant.

Although waterfowl are notoriously tough when it comes to the cold, they were rendered helpless during the 1977 cold spell, when every last drop of their estuary home froze solid.

With no access to food, the birds moved into populated areas.

Brant are an extreme specialist, feeding on aquatic saltwater vegetation, with none of the flexibility in food and habitat that generalists like mallards and Canada geese possess.

The best the brant could do was gather on lawns and ball fields and pick at the brown, frozen grass.

In an essay published in the Bulletin of the Cape May Geographic Society, naturalist Ernest Choate wrote that local municipalities, agencies, volunteers and non-profits jumped into action and set up a series of waterfowl feeding stations throughout the state, where the birds were fed “grain, green pellets, bread and civil emergency defense rations.”

The black ducks and other waterfowl took well to this artificial food, but the brant did not have the capacity to recognize and accept the offering.

They “died of starvation by the thousands right in people’s backyards.”

Some people went a step further to help the brant.

The Wetlands Institute in Stone Harbor, NJ provided space to build a makeshift brant rehab facility. Staff at the Institute, along with renowned naturalists Pat and Clay Sutton, bayman and decoy carver Jim Seibert and others brought a flock of 80 weakened birds into care. Another local facility brought in a similar number.

It was a leap of faith.

No one had any idea how to take care of brant and whether they would take any of the food they offered.

Hoping for the best, the rescue workers set up a buffet with a variety of menu items. Luckily, the brant bellied up and began eating.

Today, Pat and Clay recall that the birds’ clear favorite was commercial turkey chow. They also note that having a bath was the major secondary priority for the brant, with the birds jostling for position in the little tubs that volunteers provided.

Once the coastal waters thawed, the now fat and happy brant were released.

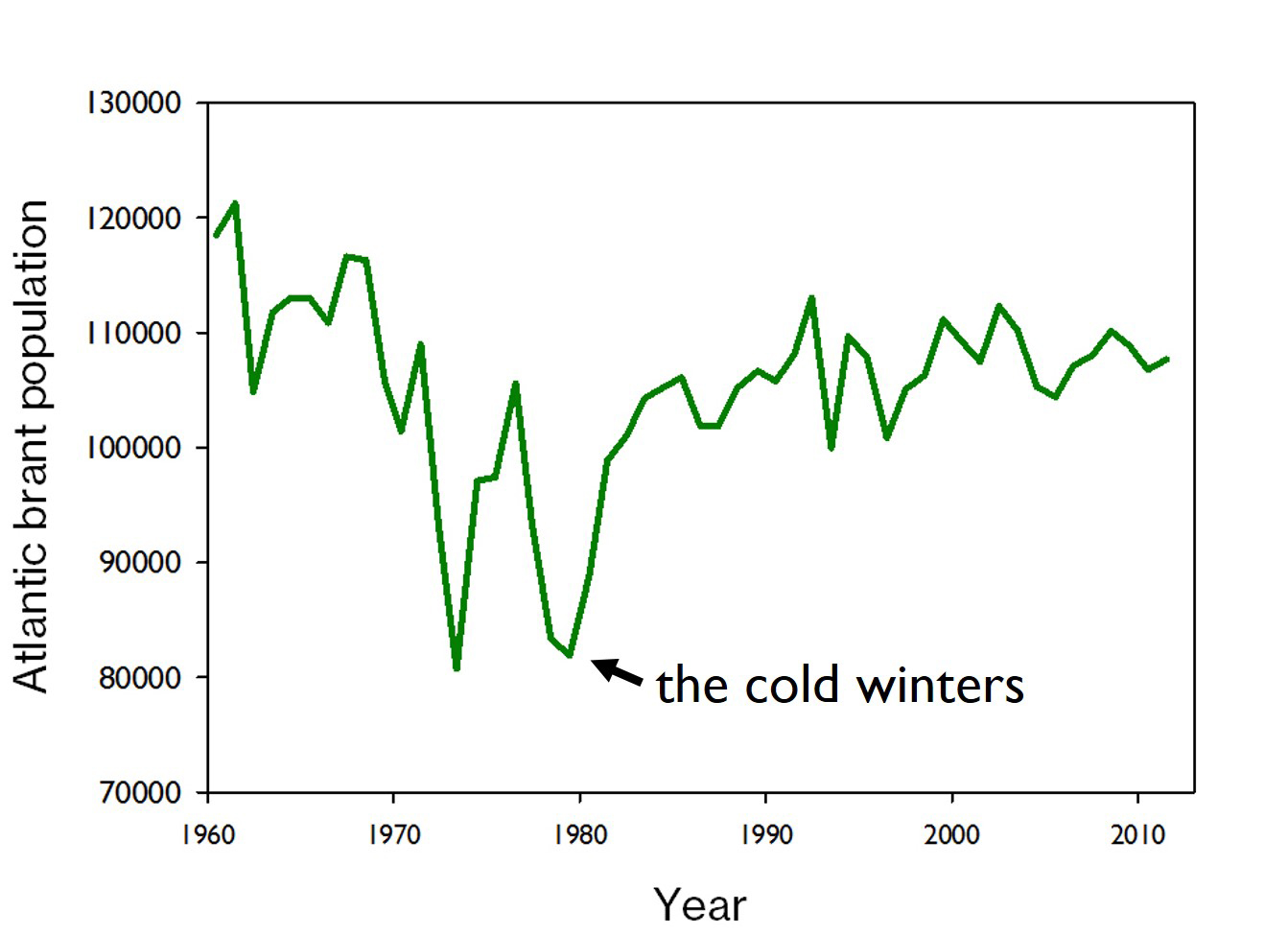

Despite the effort of these dedicated folks, the toll on brant was still great. Biologists estimated that more than half of the east coast’s wintering brant population died that winter.

The songbirds of Illinois and the brant of New Jersey give us a peephole view into what must have been a massive die-off of wildlife across the eastern half of North America.

In the winter of 1977, many animals reached the limits of their survival. In such cases, nature has a second line of defense. As long as some individuals survive, populations can bounce back. Often survival and reproductive output increase among those that remain because there are more resources to go around.

It is unlikely that the cold winter had any long-term impact on bird populations. For example, Atlantic brant populations recovered over the course of a few years.

What if the cold winters weren’t an anomaly and they kept on coming year after year?

There would be no bouncing back. Songbirds like Carolina wren would experience a range contraction southward into regions with warmer climates. Specialists like brant might disappear altogether.

Although an era of endless cold winters is a fantasy, we are now experiencing an era of continuous warmer-than-average winters.

A series of balmy winters won’t cause our backyard birds to keel over, but such weather may take a toll on plants and animals in other ways.

For example, in southern parts of their range, survival of yearling moose is now very poor because warm winters allow ticks to proliferate throughout the winter. The young moose succumb, overburdened by the parasites.

If the warm winters continue, moose might experience a range contraction northward, disappearing from parts of their range in the United States.

All around us the warming climate is having both subtle and dramatic effects on the lives of plants and animals. Many scientists have devoted their lives to documenting these effects in order to share with the rest of us the consequences of a warming world.

The challenge now for us all is take stock of these real and predicted consequences on the people, places and critters we care about.

Then each of us needs to decide what we are going to do about it.

Join the Discussion

4 comments