Every winter, birders wonder: will this be one of those years?

One of those years when snowy owls dot the windswept landscape and our woods are filled with saw-whet owls.

Or one of those years when our feeders are inundated with northern seed-eating songbirds like purple finch, red-breasted nuthatch, evening grosbeak and redpoll.

These birds only occasionally descend in large numbers from their boreal and arctic nesting grounds to more southern latitudes where most of us live.

Such irregular appearances of typically northern birds are known as irruptions.

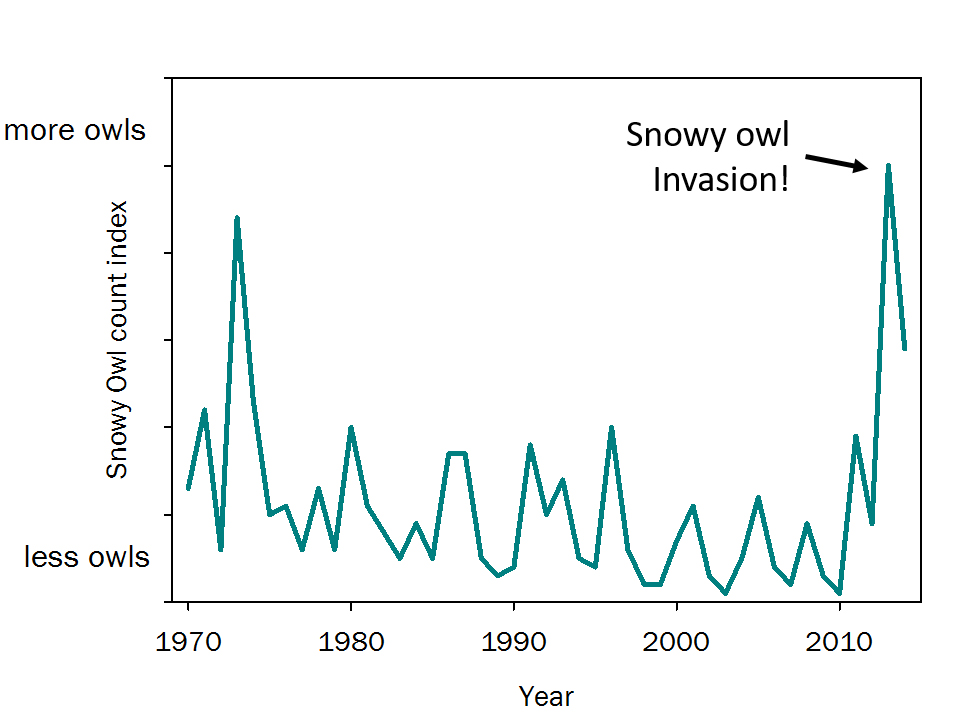

One of the most memorable irruptions in recent years – one that captivated birders and Harry Potter fans alike – was the snowy owl invasion during the winter of 2013-2014.

New research has shown that the abundance of snowies we saw in 2014 was the result of a particularly good nesting season on the Arctic tundra.

The banner year for baby snowy owls was courtesy of lemmings, the owl’s #1 food source. A population boom of lemmings translated to a population boom of owls.

The study found that in big lemming years, birders counted higher numbers of snowy owls during the annual volunteer-driven Christmas Bird Count.

Irruptions represent either an actual population increase, as in the case of snowy owls, or a change in movement patterns. These movements are often triggered by booms and busts of food availability.

Under typical conditions, irruptive bird species stay put in the far north, finding what they need to survive during the deep cold of winter. But when necessary, the birds spread east, west and south across the landscape in search of better prospects.

The fortunes of several other northern owls are also linked to the population cycles of lemmings and voles.

Like snowy owls, saw-whet owls experience population booms when rodent populations peak. In years of high vole abundance, the abundance of young saw-whets spikes.

Unlike snowy owls, saw-whets don’t plop themselves in conspicuous places in broad daylight. We know about saw-whet population cycles thanks to a dedicated network of owl banders who tend mist nets all through the night to coax owls out of the darkness.

While snowy owl and saw-whet owl irruptions are the result of an abundance of food, irruptions of other owl species appear to be related to food scarcity.

Northern hawk owl, boreal owl and great gray owl all appear in large numbers at southern latitudes when there are fewer rodents in their typical, far-northern winter range. A study in Quebec demonstrated that irruptions of all of these owl species occurred every four years when rodent population cycles bottomed out. In this case, the irruptions represent a change in the movements of owls rather than a change in their population.

Food scarcity seems to explain the irruption of winter songbirds as well.

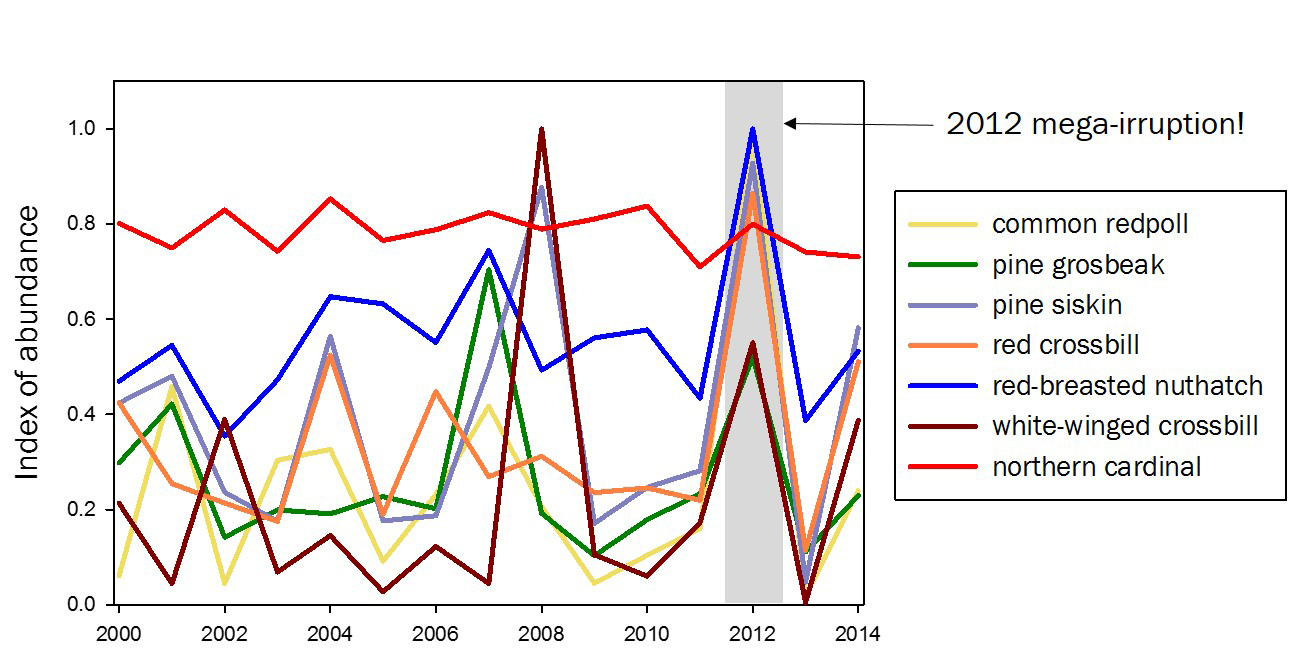

In any given year, one or a few of these species may be experiencing an irruption. In legendary years, a whole bunch of species irrupt at once. 2012 was our last mega-irruption, when pine siskin, red crossbill, white-winged crossbill, red-breasted nuthatch, redpoll and pine grosbeak all appeared in big numbers.

A study that used Christmas bird count data along with data on the cone and seed crops of evergreen trees of the boreal forest found that irruptions in many of these songbird species arise from a sequence of seed crop boom and bust.

For some species, like red-breasted nuthatch, red crossbill, evening grosbeak, bohemian waxwing and pine siskin, irruptions occur in low seed crop years that follow a year with a high seed crop. The year with the high seed crop allows bird populations to increase and survive the winter, but the following year’s food scarcity drives many hungry mouths southward in search of food.

Given the complex patterns of food scarcity and abundance across the continent that drive irruptions, a given year may offer one or two marquee irruption species, a whole bunch of them (as in 2012), or none at all.

A more recent study that focused on pine siskins offers deeper insights into how irruptions work. Pine siskins breed and winter across Canada’s boreal forest and appear further south during irruption years.

The study used bird observation data collected by people with backyard bird feeders as part of Project FeederWatch, operated by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Bird Studies Canada. Participants contributed more than two million siskin observations at sites across North America.

Pine siskin observations combined with climate and evergreen tree seed abundance data showed a see-saw pattern of seed production across North America. Birds moved in predictable patterns toward regions with high seed availability.

Wet and cold conditions during spring and summer produce smaller seed crops, while warm and dry conditions produce larger seed crops. In any given year, climate patterns dictated that if the western boreal forest is warm and dry, the east is cool and wet. The same see-saw effect occurs in northern and southern regions as well. Siskins “irrupt” into regions where there are better feeding conditions.

This research is a first step toward using climate data to predict irruptions – moving us closer to knowing rather than wondering whether the coming winter will bring northern birds.

In the meantime, the next best thing is Ron Pittaway’s annual winter finch forecast. It is a fascinating read that evaluates regional tree seed crop patterns to make predictions about how the different irruptive songbird species will respond.

So. Is this one of those years? Alas, it is not. At least not a mega-irruption year – those come along very rarely.

Slow years are part of the game, but most winters have at least a few highlights. Judging from eBird sightings, this winter of 2016-2017 has been the best for red-breasted nuthatch since 2012, and it is a better-than-average year for seeing bohemian waxwing and purple finch. Snowy owls seem to be present in average numbers (check out Project Snowstorm for live maps of snowy owls wearing tracking devices).

For birders, irruptions are a form of “intermittent reinforcement.”

This term stems from B.F. Skinner’s studies of operant conditioning. When a particular behavior only occasionally provokes a reward, it actually strengthens the impulse to perform the behavior.

The most famous example of this is a slot machine. If you always win or always lose with each pull of the handle, engaging with the one-armed bandit would be a dull affair.

Likewise, if we were knee-deep in snowy owls every year, they wouldn’t be as exciting. Imagine how spectacular cardinals would be if you saw them only once every four years.

For winter birders, owl and songbird irruptions are a birding slot machine. Each year is another pull of the handle. Maybe next winter will be the year!

Here in Atlanta, I have been blessed this winter by the appearance of several species I had not seen very often. This includes all 3 species of nuthatch together, and occasional goldfinches (these are normal visitors, and one of my personal favorites). There are a few more that I haven’t fully identified yet (I am a relatively rank amateur birder). We also have all our “normal” regulars, including Eastern bluebirds, house finches, cardinals, mourning doves, mockingbirds, and an occasional large raptor or two, along with some not so welcome visitors like starlings and cowbirds.

I believe that I have twice seen snowy owls—once in Claremont, CA, and once in Baja CA at a lodge for duck hunters on the coast. The sighting in so cal was twenty years ago, and the one in Baja forty years ago on my honeymoon. I had no one to confirm the sightings, but I am still certain that the birds were snowy owls—I presumed that they were lost. Am I nuts or is this possible? I am a somewhat experienced

birder…. Thank you! Susan Kerr, azucena@pacific.net

Dr. Smith, what was your reference for the graph showing Snowy Owl irruptions?

Living in northern Virginia there are lots of small birds visiting the yard and the feeders during the winter including Blue Jays, Carolina Chickadees, Cardinals, Tufted Titmice, White-breasted Nuthatch, Downy Woodpeckers, Carolina Wrens and Mourning Doves. However, this is the first year in nearly 20 that I’ve spotted a Red-breasted Nuthatch. He has become a regular visitor.

Save all the Birds.

We have just had flocks of Wax Wings huddle in our Holly tree. We get them every year around the middle of Feb. This year they let a flock of Robins enjoy the berries, too. We are from MN and have called these birds Cedar Wax Wings but your article called them Bohemian Wax Wings. Are they one and the same?

Thank you…..

Hi Bruce, Thank you for the question! They are mostly very similar looking species, but if you can get a good look at their wings, the Bohemian Waxwings have more elaborate wing decoration than Cedar Waxwings. See the species ID guides on All About Birds for more detailed information. Cedar Waxwing: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Cedar_Waxwing/id Bohemian Waxwing: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Bohemian_Waxwing/id

Living in northeastern Minnesota, the most common birds I have at my feeder in winter are common chickadees, red-breased nuthatches, pine grosbeaks, pine siskins, and common redpolls.

Sometimes we get hairy redpolls, grey jays, purple finches, and (rarely)goldfinches.

Away from the feeder I have also seen saw-whet owls, boreal owls, great grey owls, northern hawk owls, barred owls, and great horned owls over the years.

It’s all fun.

American Goldfinch and Pine Siskin

Common redpolls.

and continued great articles such as this one..