What can we do to slow climate change and restore America’s forests? I used to think the answer was to plant more trees. Boom. Done. Mic drop.

But wait, that’s not the whole story.

Our remaining forests face great challenges like massive wildfires and invasive forest pests. Managing for this array of threats in a changing climate is complicated. Forest managers are researching strategies that can keep forests resilient under multiple stressors so that they can continue to provide habitat for wildlife, clean air, clean water, carbon storage, and, yes, timber far into the future.

Old-growth forests have stood for centuries, surviving the same kinds of challenges that forests face today. That’s why today’s forestry specialists, including scientists at the Nature Conservancy and the University of Washington are looking to them for clues to manage the dry fire prone forests of eastern Washington and Oregon, through which fires once naturally swept every 10-20 years.

They call it an old-growth forest, but not all of the trees are old. Through natural processes like disease and fire over time some trees die leaving openings where young trees have a chance to grow. In some places, perhaps because of soil conditions or past fire events there are large clearings. A healthy forest is a diverse mix of young and old trees, dead trees, and openings. Spatial diversity (in addition to biodiversity and genetic diversity) increases the resilience of the forest.

Creating a Formula for Randomness

How can scientists, land managers, and foresters recreate this seemingly random mix of conditions in forests that have been altered by fire suppression, logging, and where natural forests have been transformed into plantations with evenly spaced stands of uniformly aged seedlings?

Enter science and the power of statistics.

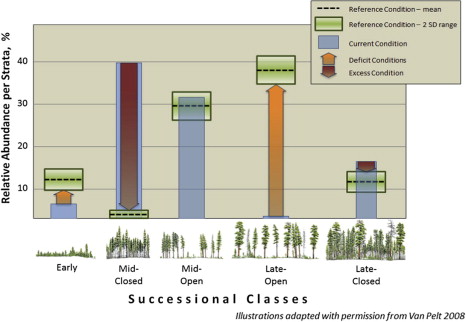

Looking at satellite images and historical aerial photos of old-growth forests for reference, researchers found that forests were made up of a mosaic of individual trees, clumps, and openings (ICO). Working with dry fire prone forests, researchers quantified the average number of individual trees, clumps, and the area of openings statistically likely to be found over one hectare in a given climate. These natural references provide guideposts for the “ICO” (individuals – clumps – openings) approach to determining which trees to remove and which trees to leave during ecological restoration thinning projects.

The need for this type of ecological restoration thinning in the dry forests of western North America is great. For example, across eastern Oregon and Washington, a study led by Ryan Haugo of the Nature Conservancy in Washington found that 41% of forests in the region are currently too dense compared to reference conditions and would benefit from the removal of some trees by fire or mechanical means, including logging.

Patterns vary from region to region and even from watershed to watershed. However, once they’ve been calculated for an area, managers have a goal to work toward and a benchmark to measure success.

The ICO approach to restoration thinning works best in even-aged forests — often those that were replanted by people in the past (whether after logging or fire). Since these forests are often dense compared to natural reference conditions, the focus of management is on tree removal whether by fire or mechanical thinning. Once openings are created, trees will seed on their own and young trees will grow in naturally where conditions permit, so tree planting is not typically part of the management recommendation.

Wait, Why Can’t Forests Recover Without Intervention?

In 1994, the South Canyon Wildfire swept through Colorado killing 14 firefighters and scorching 2,115 acres. While South Canyon was relatively small in size compared to recent wildfires, it was a turning point for the forestry community. People realized that something was out of whack.

Hundreds of years of logging and replanting (in evenly spaced stands of the same aged trees), good management for maximizing timber production, had created homogenous forests, with few remaining large (i.e. more likely to survive a fire) trees or natural openings that might slow or stop a fire. On top of that, a hundred years of fire suppression left dense underbrush — fuel for a high-intensity fire (one that burns half or more of the forest canopy and everything on the forest floor).

Many of our forests remain homogenous and overgrown and, while there is lingering disagreement on how to restore diversity and resilience, forestry scientists agree that something needs to change.

Without management, these forests will remain prone to high-intensity wildfires and increased damage from forest pests. Events that threaten people, release large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere, have the potential to cost hundreds of millions of dollars, and from which some species of trees and areas of the forest may never recover.

The goal of the ICO approach is not to perfectly recreate the forests of the past, but to recreate the varied conditions that allow old-growth forests to survive and thrive for long periods of time. Some trees will die in prescribed fires or through removal, but a healthier forest will remain.

Come back tomorrow to learn how technology is helping foresters implement an ICO approach on the ground.

I agree you have to manage a forest underbrush and the denseness of the trees. I have 11.5 acres on Camano Island WA and I did a selective logging about 24 years ago. when I went to DNR to put in for a permit for logging I remember that I had to show DNR where my skid roads where on a plot map and the landing area to prosess and load the fir trees. also there was a question on the application on how I was going to take care of the undergrowth after logging? Burn, Mechanical, or By Hand slash. Well I had the trees skidded out with the limbs on and we buck the trees at the landing and of course I used a burn pile at the landing to take care of the limbs after bucking the logs. I did not notice just how fast the undergrowth grew until about 5 years later and of course there was no way I could hand slash 6 acres. So I purchased a backho and cleaned up the old broken branches and undergrowth with it. It worked out ok but the under growth grew faster now. So I purchased a caterpillar and a mulcher head and a stump grinder to clean the ground around my forest and this works well for my small acres. I have worked in the Apache forest in Ariz clearing underbrush and doing ” conservation work” and I love it. I have had friends that where loggers from the 1940 and on and I have learned from them about the logging industry. I just closed my business of Heavy Brush and land clearing to retired. what I have noticed is that the logging that is going on here in Washington State and in Oregon state is they just leave the stumps and slash on the ground, hardly any clean up and then they come back in and plant new saplings in around the stumps and slash. I know it cost to do a better cleanup but I think with all the forest fires and global warming going on we got to remove the tender box of slash on the forest floors and by mulching the slash is a good way of getting the tinder box removed and the mulch that is left over helps slow down the growth of weed and puts back the nutrients faster in the forest floors. I would enjoy getting any feedback ” positive or negative ” Just remember I am only Human and I make mistakes too! But that’s how I learn.

The assertion that “thinning” dense national forest stands (thinning is rare on industrial forest holdings) will reduce tree loss to wildfire is an essential part of TNC’s argument for more national forest logging. But, as a growing body of scientific reviews have found, that is not always the case: even where short term fire risk has been reduced, thinning results in more fuel-related fire risk as soon as five years after “treatment”.

The reason is that the FS is institutionally and culturally incapable of committing to the follow-up treatments needed to sustain/extend the fuel reduction benefits of “thinning”. Furthermore, the tool the FS is using to “thin” both second growth and younger natural stands is the timber sale contract. When the timber sale contract is the tool, it is timber economics, not what would most benefit the forest, that determines what gets cut. In particular, FS “thinning” generally reduces canopy closure to 40-60%. That reduces competition of remaining vegetation for water, leads to accelerated reproduction of trees and sprouting of shrubs, as well as introducing more drying winds. As a result, fuel loads (especially fuel loads near the ground) are typically greater 5 to 8 years after “thinning” than they were before thinning.

What I write above is based on what actually takes place on the ground in NW California and SW Oregon where TNC is backing massive BLM and FS “thinning” that – if it happens – will result in more fire risk for communities except in the very short term. Even then, FS and BLM leave slash heaps untreated for years; those are places fires can and have blow up into firestorms.

I and others have been working to protect and restore national forests in NW Cal and SW Oregon for going non 50 years. Now comes TNC pushing logging. I wish these TNC folks y would go back to wherever they came from.

I am involved in a family owned forestry program in NC the question we are debating is: whether thinning our forest makes it a healthier forest? Some say leave it alone others believe thinning of harvesting some trees will result in a healthier forest. Can you direct me to helpful

research?

Is there anything that a small property owner can do to improve the “health” of his land? I think I might get in a bit of trouble if I attempted a controlled burn of the underbrush. Invasive species take hold quickly, before they are even recognized. I hesitate to cut down even dead trees when I see what’s living in them. And in some places, local regulations encourage (or require) practices that are not helpful.

Hi Mark, I checked with Ryan Haugo about this – “In terms of what a small property owner can do, this depends very much on what type of forest environment / ecosystem they are in. If they are within dry, fire-prone forests the first and most important steps are following the principles from the Firewise (www.firewise.org) and Fire Adapted Communities (http://www.fireadapted.org/) networks. Next, we (TNC) certainly acknowledge that the goals/objectives for restoration and resilience on large public forestland owners are very different than for small private forestland owners. It’s probably most useful to connect with your local TNC chapter for direction to correct local resources.” Let me know if I can help you find contact info for a program or chapter, this page is a good place to start: http://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/index.htm?intc=nature.tnav.ourwork

What can we learn from the Europeans, good or bad, who have been managing their forests for a lot longer than we have?

Hi Michael, Thank you for the question! I checked-in with Ryan Haugo for a response — Much of 20th century forestry in the western US was attempting to follow a “European Model”. This is one of the factors lead to the current disconnect between forest conditions and the natural functioning of western forest ecosystems (e.g., wildfire). The European approach and western ecosystems were a mismatch. Moving away from the European, individual forest stand focused, approach is one of the central themes of the “seven core principles for restoring fire-prone inland Pacific landscapes” that I recently published along with a number of prominent forest and fire ecologists: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10980-015-0218-0

Agree logging in clear cuts I feel is the start of BAD things, brought on by Greed!

I love all trees.

This is really helpful. One difficulty I have in working with potential donors is that when we use fire, we are contributing to climate change. Some complain about smoke/health issues. How do we weigh fire/climate and fire/health issues?

Thank you Carol! This is an excellent question and I’m checking back with the scientists to get more information on it. More soon.

Hi Carol, Thank you again and I’m sorry for the delayed response. Depending on where you live, you might consider checking your state’s prescribed fire council (e.g., http://waprescribedfire.org/). You can also read some more about this issue in our “Good Fire, Bad Fire” post: https://blog.nature.org/2013/05/15/good-fire-bad-fire-an-ecologists-perspective/

If anyone believeshe that the federal government can manage anything, especially our national forests, they need therapy. The federal government is so huge and the problemsolving of our forests are mostly local. National Forests have been combined and Ranger Districts have been combined to the point that a Ranger has no control. By the time a forest insect is identified as a problem, it is 7-8 years before it might become a Timber sale. More than likely, an environmental group will stop it in court. The only solution is for all manageable federal forests be turned over to states. At least they can still harvest Timber and save our streams and wildlife from burning to a crisp.

Great story Lisa, and great work conservation colleagues!

Thank you Jim!