An outboard motor roars in the distance, quickly approaching the island as the sun crests over the distant horizon. News spreads quickly through camp — they’ve caught another turtle.

The boat pulls into the cove and the conservation officers lift the hawksbill out of the boat — thrashing as each man carries her carefully by carapace and flipper. Sand obscures her rich, mottled brown shell and salt crusts the corner of her large, black eyes.

I’m here with Nature Conservancy scientists and local conservation officers in the Arnavon Islands, where we’re tagging nesting hawksbill sea turtles with satellite trackers to discover where these turtles forage in-between nesting years and the migration routes they take to get there.

Four Islands On A Far Horizon

As you arrive by boat — 60-horse outboard motor roaring in your ears and flying fish soaring on either side of the bow — the Arnavon Islands are mere smudges of greenish-grey on the horizon, seemingly inconsequential spits of land in a world of reef and mangrove, forest and sand. On most maps they’re barely discernible — or are missing entirely.

But these four small sand islands support the largest hawksbill turtle rookery in the entire South Pacific.

Like many other sea turtle species, hawksbills (Eretmochelys imbricata) are critically endangered. Worldwide populations have declined about 80 percent in the past three turtle generations due to the illegal turtle shell trade, egg collection, harvesting for meat, and habitat loss from beach development and climate change.

“It’s really surprising that there are any turtles left at all,” says Richard Hamilton, director of The Nature Conservancy’s Melanesia program.

With assistance from the Conservancy, in 1995 the Solomon Islands government and the communities of Kia, Katupika, and Wagina established the Arnavon Community Marine Conservation Area (ACMCA), creating both the largest and first community-managed marine protected area in the country. As of 2012, an estimated 400 to 600 hawksbills nest here annually, migrating thousands of kilometers back to their natal beach. These hawksbills nest only once every 7 years, on average, so the total Arnavons’ nesting population numbers between 2,000 and 4,000 turtles.

Those numbers are just a fraction of the thousands of turtles that nested here before the shell trade nearly eliminated the species entirely, yet it’s still an encouraging trend. Data collected by ACMCA conservation officers show that the number of nests on the Arnavons has more than doubled in the two decades since establishment of the protected area.

But protecting the Arnavons is not enough. Females in this population nest once every seven years on average, spending just a few months in the protected area before returning to their foraging grounds elsewhere in the South Pacific. Once they’re out of the Arnavons they’re on their own — and we’re not entirely sure where they go.

10 Turtles, 10 Tags, and 10 Days

It takes three able-bodied men to hold the turtle on the wood-plank workbench — one to the front, one to the back, and a third waiting to grab hold as she lunges towards the beach just a few meters away, the small claw on each of her flippers scraping into the wood.

This female — named Dora by donors supporting the program — is the second of our 10 turtles. Simon Vuto, a marine scientist at the Conservancy, carefully wraps a plaid dish towel around her eyes to help keep her calm as we set to work.

First, volunteer Mick Murray uses sandpaper to rub away the grime off the very top of her carapace and then washes it with rubbing alcohol, revealing the beautiful, mottle-brown shell. Next, cloth matting coated with a thick layer of epoxy forms the base, onto which Hamilton and Vuto affix the satellite tracker with two thick rolls of grey putty. After a few minutes of drying time, they seal the tracker to the turtle’s carapace by wrapping its base in more layers of epoxy and matting, every last seam coated thoroughly with tiny, glue-gummed paintbrushes.

Dora remains calm throughout the process, her flippers draping over the sides of the bench and dish towel blocking the flurry of activity around her. “She looks like she’s having a spa treatment, eh?” jokes Hamilton as he paints on the final layer of epoxy.

The tracker’s orange light blinks slowly beneath the amber plastic cover, transmitting our position to a nearby satellite. About the size of a brick, this tracker will attempt to record Dora’s GPS location eight times in a day when she surfaces to breathe.

“It’s going to be very exciting future for these 10 turtles because there are so many questions that we don’t have answers to,” says John Pita, the Conservancy’s environment coordinator for Isabel province. “This research will help us answer longstanding questions on migration between feeding and nesting habitat.”

These data will be some of the first information on where Arnavons turtles migrate to in between nesting years. Existing information suggests that they swim to foraging grounds on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef and Papua New Guinea. But these data come from a mere five turtles, only two of which were satellite tracked showing the exact migration routes.

“If this turtle goes back to somewhere like the Great Barrier Reef, she might travel as far as 1,800 kilometers in a month,” says Hamilton. “These hawksbills have one of the longest intermigration periods in the world; she might not be back to the Arnavons until 2021.” For comparison, hawksbills that nest in Hawaii travel only ~200 kilometers between nesting and foraging areas.

If this turtle goes back to somewhere like the Great Barrier Reef, she might travel as far as 1,800 kilometers in a month.

Richard Hamilton

“But we don’t know if those earlier satellite-tagged turtles were typical or if they were the really long distance migrants,” says Hamilton. It’s possible that some of the Arnavons turtles migrate to foraging grounds closer to their natal beaches. He plans to tag an additional 10 turtles in 2017 and 2018 to see if the migration routes and foraging grounds change from year to year. “This is one of the only places in the world where you have year-round nesting, Hamilton says, “so it’s possible that you have turtles coming from distinct foraging grounds in different years.”

While existing data give us some indication of the foraging grounds, no information exists on the second important question about hawksbill movements: where the turtles spend their time while they’re in the Arnavons protected area. A female hawksbill will lay between three and five clutches of eggs in a nesting season, typically about two weeks apart. But we don’t know if those turtles stay within the 152-square-kilometer protected area or if they roam farther afield.

The tracker currently affixed to Dora’s carapace should collect data for up to a year, recording her location within the Arnavons, her migration back to the foraging grounds, and her movements during foraging.

A Region-wide Approach to Turtle Conservation

At 5:00 p.m. the epoxy was rock-hard and the tracker secure. Dora had spent most of the day resting quietly in the shaded pen, regaining her energy, but as evening fell the fiberboard walls shook periodically as she smacked against them.

“She’s ready to go, isn’t she?” said Hamilton, smiling as Dora craned her head upwards toward the light and snorted emphatically.

Vuto removed the pen’s shore-side wall as Hamilton, Pita, and an entourage of conservation officers and tagging volunteers looked on. After a few seconds of calm Dora was off, hauling herself across the sand in five-push bursts. The tracker blinked once as she hit the water, and within a second she was speeding under the nearest boat and off into the fading light.

From the Arnavons to New Georgia

“Let’s see where they’re going, eh?” said Hamilton, flipping open his laptop as we settled in around the table.

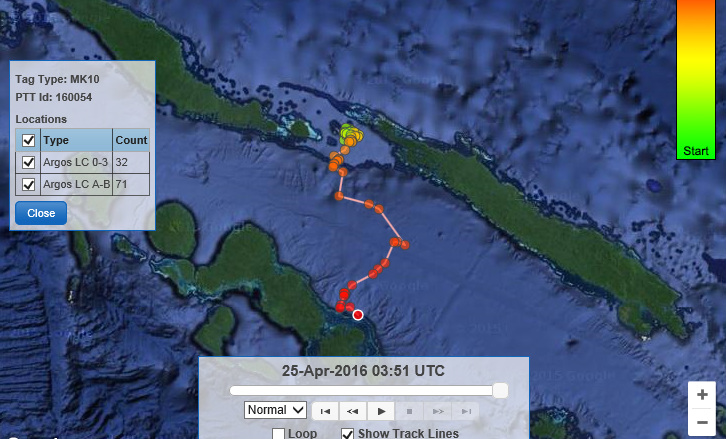

Hamilton, Murray and I were back in Brisbane a week later, huddling around the computer screen as the latest data loaded onto the screen — blue, green, yellow, red and orange circles appearing in a dense cluster around the Arnavons as we pulled up each turtle’s track.

Until we clicked on Dora.

Within one week of tagging she headed for deep water, traveling 130 kilometers in three days as she swam south to New Georgia before moving gradually eastward across the coast. “I reckon she may be on her way back to Papua New Guinea,” said Hamilton, zooming in to the latest GPS location. It was likely that Dora had arrived ahead of the major nesting peak and had already finished nesting by the time we tagged her.

“It’s like a migratory pathway on the high seas,” says Hamilton. “It’s very, very cool.”

Three days later we realized that Dora wasn’t alone. A second turtle was swimming away from the Arnavons and was following her route almost exactly — the multicolored spheres of their routes overlapping against the familiar blue and green backdrop of GoogleEarth.

Two turtles traveling south across a wide, wine-dark sea.

To study their movements, the researchers attached solar-powered tags to 24 green and 20 Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle toddlers in the Gulf of Mexico and deployed passively-drifting surface buoys. The turtles were tracked by satellite for a maximum period of two to three months before the tags fell off. The researchers then compared sea turtle movement to the movement of the drifters.