Something was wrong with the turtle we call PT-160051.

It was near midnight on Wednesday 3 May, and the satellite transmitter we had affixed to her shell 16 days earlier had stopped working. Programmed to record a GPS location every three hours, the tracker showed no readings after 7:37 p.m. that evening.

With a growing sense of unease, Richard Hamilton, director of the Nature Conservancy’s Melanesia program, quickly checked the location of the other nine hawksbill sea turtles — all were accounted for. He wondered if the tag had malfunctioned — possible but unlikely — or if something far more grim had happened.

The uneasy silence continued the following day. And by nightfall Hamilton realized that a second turtle was missing.

The Weak Link in Protecting Hawksbills

Some six hours earlier in Wagina’s Nikumaroro village, a group of men quietly loaded their boats with petrol, flashlights, and machetes, and set out to sea under the cover of darkness. They were heading for the Arnavon Islands, and they were hunting turtles.

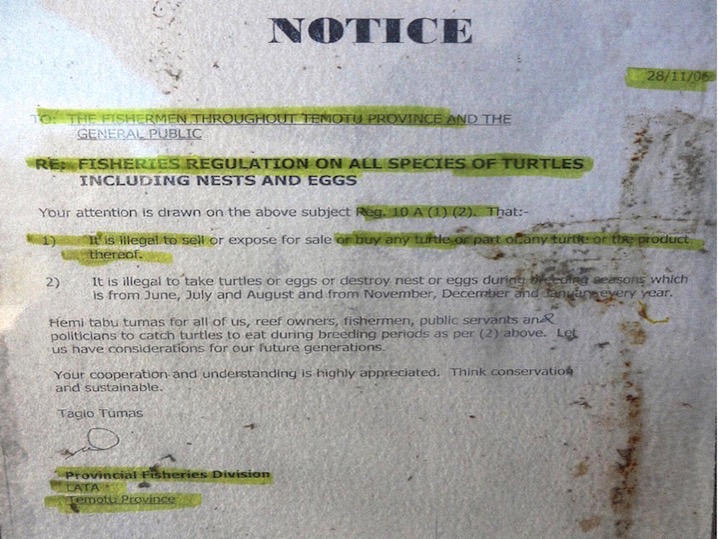

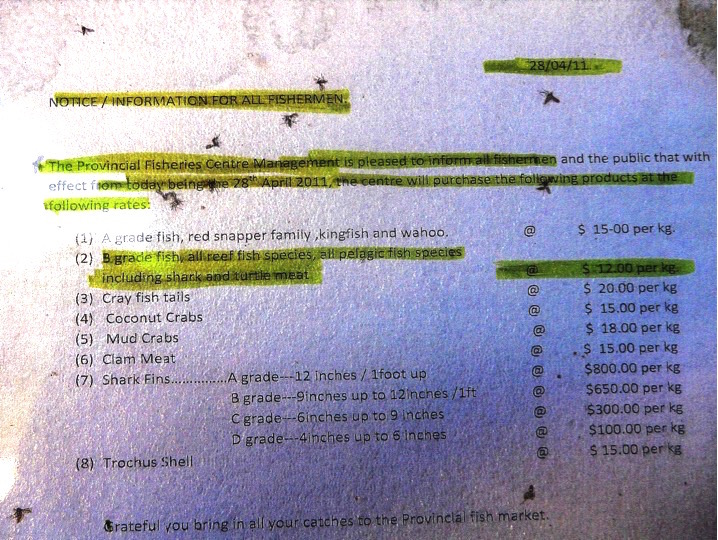

It’s still legal to kill a sea turtle in the Solomons — but only for subsistence. In addition to the prohibitions on trading endangered species under CITES, the Solomon Islands 1998 Fisheries Act also makes it illegal to kill a nesting turtle (one that has crawled ashore to lay eggs) and to sell, purchase, or export any turtle product.

But without enforcement, these paper protections do little to stop poaching. Visitors can easily find hawksbill-shell bracelets and earrings for sale at multiple locations in Honiara, including the airport’s international departures lounge.

“The Solomons actually has great legislation for turtles, but it’s very hard to enforce,” explains Hamilton. Part of the enforcement problem is a capacity issue — money is tight and the majority of the country is remote, hindering outreach efforts. Even where law has a presence, enforcement is complicated by the close-knit nature of communities. “If you are going to prosecute someone, you are essentially prosecuting your relatives,” says Hamilton, “so you run the risk of serious backlash.”

The illegal trade is growing — fueled by the growing wealth market in China and the absence of enforcement — taking a direct toll on hawksbills in the Arnavons and threatening conservation efforts to save the species.

Hamilton had just spent two weeks in the Arnavons, tagging turtle number PT-160051 and nine others with satellite transmitters to gather data on where these females migrate to during and after the nesting season. As he patrolled the beaches at night in search of nesting females, the conservation rangers told Hamilton that they’re observing increasing evidence of poachers on Sikopo, the primary nesting beach. They also repeated rumors of a shell buyer in Wagina, one of the three communities that came together to protect the Arnavon Islands 20 years ago.

Worried by these reports, Hamilton and John Pita, the Conservancy’s environment coordinator for Isabel Province, arranged for the rangers to set up a temporary camp on Sikopo Island, in addition to the permanent camp on Kerehikapa, to monitor and protect turtles on that island during the peak nesting season.

But on the night of 3 May the island was empty. The rangers were changing shifts, and while the first group had returned to their home villages — including Wagina — the replacement crew was held up by fuel shortages. The islands were unguarded, and the poachers knew it.

The islands were unguarded, and the poachers knew it.

The Arnavons Community Marine Conservation Area and The Nature Conservancy are trying to get the Arnavons listed under the Solomon Islands Protected Areas Act, adding additional protection by outsourcing enforcement to the local rangers, granting them legal authority to arrest poachers.

While they wait for governmental approval, Hamilton and Pita have another tactic to fight the illegal hawksbill trade. Funded by a grant from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the Conservancy will soon undertake a year-long study to examine the extent of the illegal shell trade in the Solomons, from the sea all the way to the capital city.

“We really have no idea what the current harvest rates are, legal or illegal, in the Solomons” says Hamilton, “and knowing how heavily turtles are being overharvested is the first step to securing better enforcement of existing laws.”

Working with colleagues at Australia’s science agency, CSIRO, Hamilton and Pita will train community rangers from Isabel and Choiseul Provinces to record catch data for any harvested turtles, including: the location of capture and kill, date, species, length, and photos of the turtles’ reproductive organs after they have been butchered. They’ll also ask whether or not the turtles are caught for food or for sale. (Even though harvest for sale is illegal, Hamilton explains that the lack of enforcement means that many people will admit if they’re breaking the law.) The photographic data will help Hamilton gauge how many of the harvested turtles are experienced breeding females, another indicator of population health.

“We will use that data to first establish that turtles are being overharvested, whether legally or illegally,” says Hamilton. “Then we will quantify the scale of the turtle trade and use that to educate local fisheries officers on why they need to start enforcing the existing policy.”

Hamilton and Pita also plan to send contacts from the local communities undercover in Honiara to better understand how many individuals are buying turtle shell for export. They suspect that just a handful of individuals control the trade out of Honiara and on to Asia.

Footprints in the Sand

Late in the evening on 4 May an emergency dispatch came in on the radio from the rangers on Sikopo; poachers were roaming the island, searching for turtles that crawled out of the water to nest. The rangers needed backup, fast. Pita answered the call, sending a boat of reinforcements speeding across the channel from the main base.

The two groups of men confronted each other on the beach. Things took a violent turn, the poachers yelling and throwing stones, forcing the rangers to retreat for their own safety. Darkness obscured the poachers’ faces, but the rangers caught a good enough look at their boats to recognize them — it was the Nikumaroro fishermen.

When they returned an hour later the poachers were gone, leaving nothing but footprints in the sand.

It would be another 24 hours before Pita was able to contact Hamilton and relay the news. Comparing notes, they came to the undeniable conclusion: PT-160051 and PT-160048 were dead. The poachers had killed our turtles for their shells, hacking off the satellite tags with a machete and tossing them into the ocean.

“For me, this incident has certainly made the situation seem more urgent,” says Hamilton. “And it reinforces the fact that success in conservation is an ongoing battle.”

As the data-gathering on the illegal shell trade begins, Hamilton and Pita are gathering funding to build a permanent camp on Sikopo Island — in addition to the existing station on Kerihikapa — which Hamilton says is a necessity if we’re serious about protecting Arnavons turtles. Hopefully, increased vigilance combined with increased protection from the 2010 Protected Areas Act will help put a halt to poaching in the Arnavons.

“It’s a major setback, but it’s not time to walk away,” says Hamilton. “It’s time to strengthen our resolve.”

Please do not encourage these people. Do not buy or wear endangered species jewlery or hair pieces. Please join us in our efforts to protect turtles and put a stop to selling this crap, and harming animals sea creatures and yes man.

Hi Justine,

Thank you again for this piece of information. Yes, based on the research carried out previously, it also show that people of Nikumaroro the most frequent poachers from the MPA. A option could be if Ministry of Fisheries in collaboration with TNC help set up a monitoring point for fishermen on the island. The presence of the enforcement officers could solve the issues for meantime.

Once again thank you for the wonderful update.

Rishi

Poachers must be stopped. This is probably the hundredth animal species I have heard of that is endangered because of poaching. What is wrong with them?! Killing innocent hawks-bill turtles and selling their shells as products is horrible! What can I do to help you stop them?

It’s time we stepped up to help & protection these treasures. Let’s get this done. We don’t seem to value our resources, nor the others living on this planet.

We have trashed the planet, & plundered the life here. When will it end… A big bang.

Stop the insanity now, before it’s too late!!!

these people are sick with greed!

You’ve been duped! It wasn’t an accident the fuel was delayed, bozos. Get new Rangers. Haven’t you heard of the Ranger poachers in South Africa??? They were paid, their kids schooled, (with gifted binoculars and art supplies i donated, andbthe dads at the same time were auding and abetting rhino poachers!!!! Wake Up!

Poachers of any wild animal,Turtle Mammals Birds etc are the Scum of The Earth,

They and the trophy hunters should be shown no mercy if caught.

It is so terribly sad that tourists would want to purchase anything made from animals if they stopped buying these articles maybe the poaching would stop.

Soon there will be nothing left to poach then what would the brutes do? Turn to humans!!!

What a dreadful world without animals.

Please guard the islands so poachers aren’t allow to slaughter the turtles. This is a barbaric act & so cruel.

There must be a way so poachers aren’t aware of island unguarded.

We need to educate to natives and find other source of livelihood for the people so that they do not find it more profitable to kill sea turtles.