Winter is a challenging time for backyard birds such as cardinals, woodpeckers, nuthatches, chickadees, titmice and wrens.

But roosting in tree cavities, bird boxes and an assortment of makeshift shelters can help these birds stay warmer at night and give them an energetic edge.

Finding a snug place to sleep on a cold winter’s night is particularly important to Carolina wrens. They belong to a primarily tropical genus of wrens and seem to have limited capacity to deal with really cold weather and snow.

Carolina and other wren species nest in natural places such as upturned roots, tree stumps, vine tangles and tree cavities, but they also nest in a whimsical array of human artifacts. Roost sites and nest sites are often one and the same.

Birds of North America cites some favored nesting spots of the wren:

- Glove compartments of abandoned cars and inside garages.

- Old shoes and shelves.

- Mailboxes and tin cans.

- And an equally whimsical array of settings are listed as the wren’s roosting places:

- Bird nesting boxes and abandoned hornet’s nests.

- An old coat pocket and a hanging fern.

- Garages and barns.

- Squirrel nests and old bird nests.

- And at least one ceramic pig planter.

It seems that any place that can support a messy domed nest of twigs leaves, root fibers and moss is fair game for a wren.

I can add retractable awnings to the list. Every year, a pair of Carolina wrens builds its nest in an awning over my back deck – despite the mechanical activity of the awning and all the commotion below it. And in winter the pair uses the nest for roosting as well, particularly when the temperatures are below freezing.

I can be reasonably certain these are the same wrens in summer and winter because Carolina wrens don’t migrate, and pairs stay on the same territory throughout the year.

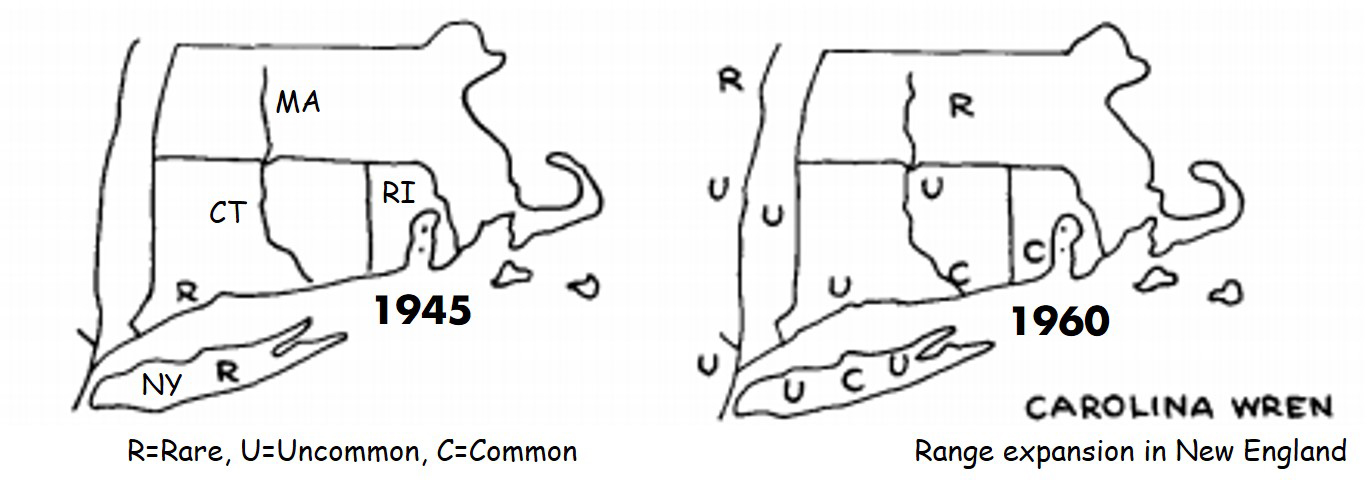

It’s been documented that the northern boundary of their range ebbs south and flows northward depending on how cold or mild the winters are over a series of years. When sustained below-zero temperatures and snow descend on the landscape, the wrens simply perish.

Near the northern edge of their range, there are clear benefits of backyard bird feeding to Carolina wrens. A study in Michigan found that bird feeding may even be supporting their northward expansion.

The research showed that in winter, wrens disappeared from areas with no bird feeders and remained common in areas that had bird feeders. It isn’t necessarily temperature that is driving wrens southward when the snow falls. It is their inability to find food during snowy conditions.

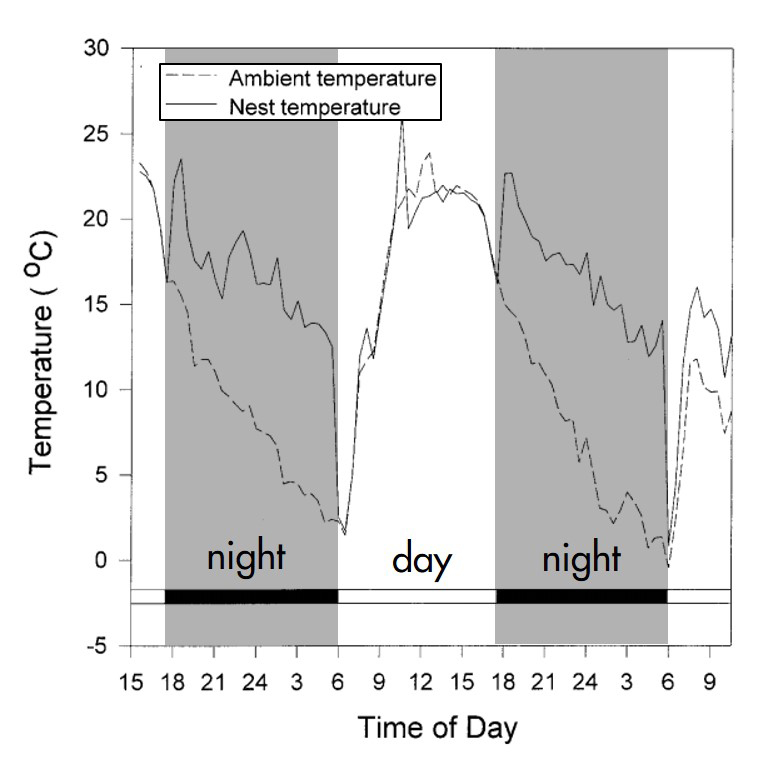

During the day, birds must eat enough to build up the fat reserves needed to keep them alive through long and cold winter nights.

Roosting in protected places gives the wrens (and other birds) a better chance of weathering the elements and conserving the hard-won energy reserves they gained during the day.

Studies of birds roosting in nests have shown that such domiciles confer critical energy savings. The same goes for roosting in tree cavities and bird boxes.

It’s not just wrens that are availing themselves of shelter when it gets cold. Woodpeckers and nuthatches nearly always use cavities to roost regardless of the weather, but chickadees and titmice resort to using cavities most often when it is very cold.

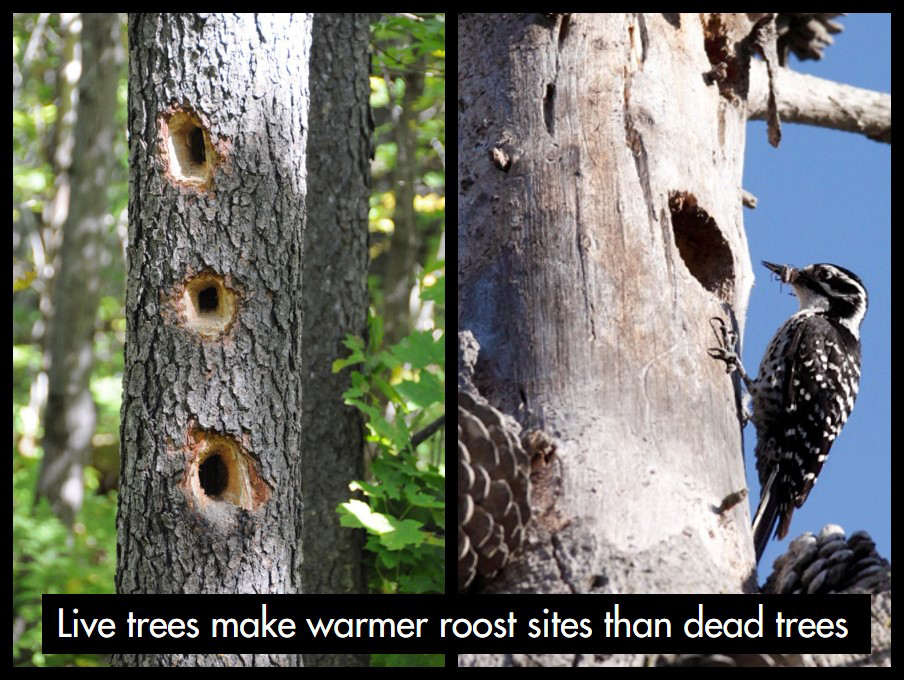

A study of the benefits of roosting in tree cavities on a cold night found that not all cavities are equal in their comfort levels. The bottom line of the research: cavities in bigger trees that are alive (not dead) hold the heat of the day longer and stay warmer at night.

In the coldest times, some species will huddle together to stay warm. In his book Birds Asleep, Alexander Skutch shares this report on the tendency of winter wrens to huddle together on cold nights:

Nine slept in an old nest of a thrush,

Ten squeezed into a coconut shell and

Forty-six into a nesting box.

One observer noted over one hundred pygmy nuthatches entering the same dead pine trunk on a cold night. Bluebirds also roost communally in tree cavities and nesting boxes during frigid spells.

In milder weather, these same species tend to roost alone or in family groups. One individual winter wren was observed alternating between roosting alone and with other birds as the temperature oscillated from mild to frigid.

While our backyard birds might be just fine on their own, we can help birds by offering places for them to roost in winter. The easiest way to do this is to have a variety of bird boxes available during winter. If you are really creative, you can try to expand the list of wacky places where wrens will nest and roost. Poke around your yard for potential roost sites and watch and listen for birds going to roost just after sunset on winter days.

I routinely spread bark butter in the depression of a tree for the woodpeckers, bluejays, and wrens. We ran out of bark butter during the recent freeze in Texas and substituted natural peanut butter. They ate it!

How would I find cardinals in winter?

Could you give me some ideas for bird boxes etc for winter protection. Make it cheap to do please.

I observed a flock of robins

near our crabapple tree —

in Hingham MA ; early January 4th 2021 with at least

30 or more in view. Temperature was

32 degrees.

I’m sorry, I had not read any comments but I live in Tallahassee, Florida.

Hi there, I loved this article. I have nest boxes in my yard which many of my birds use during nesting season. But I have a pair of Carolina wrens that nested one year in my garage in an Easter basket I left hanging. In spite of the racket of the garage door going up and down they never seemed to be bothered and we treated them royally while they raised their little family. I often see wrens in my garage but this winter I’ve noticed they are there late in the day and in early morning. Our garage door doesn’t close completely at the moment with a small opening at the bottom. I realized I never removed the old nest from the Easter basket and now I’m questioning whether or not to take it out in case the birds want to rebuild there this year? My concern is that I hate to remove the nest if there is a chance they may be roosting in there on cold nights. Do you have any suggestions? Thank you so much!

I love watching and feeding the birds! We sometimes see -40 degrees and -65 with windchill! Where do our birds go for shelter? What can I do to help? We have numerous kinds in northern Minnesota! I do put out lots of suet for our woodpeckers also! We have two of the pileated that are around and enjoy the numerous crabapples from our flowering crabapple trees. We get quite a few grouse sitting in the trees also, but haven’t seen them for awhile. Where can our many finches, nuthatches, chicadee’s and grosbeak’s get shelter? Thank you! Mostly feed black oil sunflower seeds and store bought suet.

Thank you. I’ve enjoyed your post here. Specifically about the Carolina Wren.

I’ve been enjoying the birds the past couple of years drawn to my insignificant feeders with an abundance of seed. Much strewn across my patio pavers or mulch bed.

I’ve been almost intrigued by the Carolina Wren I have as they are less and less bothered by my presence . Perhaps our current artic blast here in North West NJ has them appreciating, and maybe realizing I’m the human hand that’s offering a generous supply of seed, nuts and suet. Along with several dishes of fresh water throughout the day?

I find the Wren to be more of a loner,but hasn’t a problem when other species of birds join in for some grub.

Happy Birding.

Great! And provide water in a heated bird bath if possible so the birds don’t have to work hard to find liquid water in frigid times.

Thank you for this. Just had a chickadee go into a bird box and not come out. Your article timing is uncanny.

I lived in NC for many years and we had several pairs of Carolina Wrens on our land. One pair nested in an u used fan duct on the 2nd floor of our house, and year after year, I enjoyed watching them build their nest, raise their babies, and watching the babies fledge. I live in upstate NY now, and have missed their antics and songs. I’m glad they’re here now. I haven’t seen any yet, but I will definitely build ha itat for them and hope they come! Thank you!

Loved reading your article on Bird nesting in cold weather. As a senior and a resident of Woodlands Edge I am a Bird watcher from my upper deck. Thank you for the very interesting and informative article.

Interesting. i often wondered how birds stayed warm in the winter.

It is interesting to observe how these little birds make use of the instinct granted by the creator.

I was particularly interested in your notes about Carolina wrens. I have had them overwintering near my home in southern Wisconsin, and I think their habit of storing mealworms that I provide as well as finding cavities for roosting has helped them survive.