The forest seems endless. Standing on a ridgeline in Papua New Guinea, I can see vivid green forest stretching for miles in every direction. White mists rise from the river several hundred meters below, following the water as it winds between folded mountains.

But the dense jungle is not entirely unbroken — I can see a patch of broad-leaved banana trees and bare earth to the southwest, just barely visible amid the native vegetation.

Inconsequential as this small garden may seem amid the immensity of forest, subsistence agriculture is a major driver of deforestation here in Papua New Guinea. Hundreds of thousands of small gardens across the country carve away at the forest, threatening the region’s unparalleled biodiversity.

Here in the Adelbert Mountains, acoustic survey data collected by Nature Conservancy scientists will help inform conservation land use planning efforts aimed at protecting forests, for the benefit of both biodiversity and human-well being.

Drivers of Deforestation

New Guinea is the second-largest island in the world, and its forest is the largest stretch of contiguous forest in the Asia Pacific region. It’s also the third-largest tropical rainforest in the world, after the Amazon and the Congo.

These forests are the epicenter of global biodiversity, harboring an estimated 5 to 9 percent of the world’s terrestrial biodiversity on just 1 percent of its land. That tallies up to more than 18,894 plant species, 719 birds, 271 mammals, 227 reptiles, 266 amphibians, and 341 freshwater fish. An estimated 738 of these species are categorized by the IUCN Red List as currently threatened, vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered.

On the eastern half of the island, Papua New Guinea is still relatively lush compared to other tropical countries — 71 percent of the land area was forested as of 2002, according to a 2002 report by the University of Papua New Guinea Remote Sensing Centre. But deforestation pressures abound as a growing population utilizes the country’s vast forest resources.

The country’s population is overwhelmingly rural, with 80 percent of its people dependent on subsistence agriculture for food. Unsurprisingly, the conversion of forest to subsistence agriculture was the primary driver of deforestation between 1972 and 2002. During that same period, more than 3.6 million hectares, or 11 percent of the forest cover as of 1972, was cleared to make way for subsistence agriculture.

“Population growth and development of gardens are such a substantial cause of forest loss and degradation,” says Eddie Game, Conservancy lead scientist for the Asia Pacific Region. “That’s the fundamental reason the Conservancy works on land use planning with these communities.”

Creating Land-Use Plans in the Adelberts

Aside from high forest cover, Papua New Guinea is also unique in that approximately 97 percent of the land is owned by local people, providing conservationists an opportunity to work directly with local communities to protect their land tenure and improve their livelihoods.

The Conservancy works with communities in the Adelbert Mountains, a remote lowland range on the island’s northern coast, to create spatial zoning plans for their land. The project began in 1997, gradually expanding from three to 11 communities.

With guidance from the Conservancy, each community chose areas of their land to allocate for village development, agriculture and gardening, hunting, general forest use, and conservation. Adherence to these allocations is self-enforced and monitored by volunteer rangers from each community.

“There is a lot of enthusiasm to expand our process of land use planning,” says Game, “the provincial government of Madang wants us to bring it to other parts of this province, and other provincial governments have also asked for our help.”

The size and location of these land allotments vary greatly from community to community. The Musiamunat conservation area is 1,630 hectares, mostly in one contiguous patch, while the Irawame community’s allotments are divided into significantly smaller patches based on land ownership divisions within the community’s two clans.

Right now we don’t really know what the minimum size of a conservation area should be to preserve and maximize the biodiversity.

Zuzana Burivalova

Building the Evidence Base for Conservation

Given the large variation in size and placement of the different land use types, Conservancy scientists want to assess if the size of the conservation areas are large enough sustain target species, like cassowaries and birds-of-paradise.

“Right now we don’t really know what the minimum size of a conservation area should be to preserve and maximize the biodiversity,” says Zuzana Burivalova, a tropical forest ecologist at Princeton University. “We hope we can come up with a minimum size based on our acoustic sampling data.”

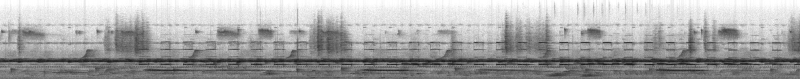

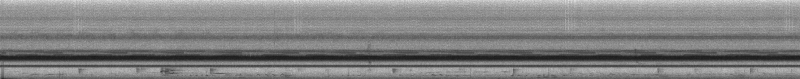

Game, Burivalova, and Conservancy conservation geographer Timothy Boucher collected acoustic sampling data from different land use types in three Adelbert communities: Musiamunat, Yavera, and Iwarame.

[cgs-juxtapose first_attachment_id=”50420″ second_attachment_id=”50421″]

Using the complexity of the forest soundscape as a proxy for biodiversity, they can compare the diversity between different types and sizes of land use. The more complex and well-defined the soundscape, the healthier and more diverse the location.

“For example, we may see that conservation and hunting areas are equally diverse, as long as they reach a certain size,” says Game, “or that the most diverse conservation areas are greater than 750 hectares.”

“We are also interested in how the surrounding land cover types influence the diversity within each fragment,” says Burivalova. For example, hunting zones bordered by conservation areas might be more diverse, and more productive for the local people.

The effect of conservation land use planning on local hunting is especially important for these subsistence communities.

“We have interview evidence from a number of communities that hunting is easier as a result of the land use planning,” says Game, “and the acoustics will help give us some indication of if there is a difference between hunting and conservation zones.”

With a solid evidence base, the Conservancy can replicate this project elsewhere in Papua New Guinea, keeping deforestation at bay and simultaneously improving the livelihoods of local people.

Join the Discussion