Climate change might change everything for conservation — both landscapes and how species might move and adapt (or not) in response.

Now a new Nature Conservancy analysis identifies locations in New England, the Mid-Atlantic and three Eastern Canadian provinces that are “flexible” enough to continue supporting native species under climate change — places with a variety of landforms and microclimates as well as high degrees of “connectedness” so species can move.

“Many other climate strategies are based on specific species — this analysis is based on places,” says Mark Anderson, the Conservancy’s director of conservation science for Eastern North America. “We want to make sure we have conservation lands in our portfolio because they support real biodiversity now and in the future…even if that’s not the same.”

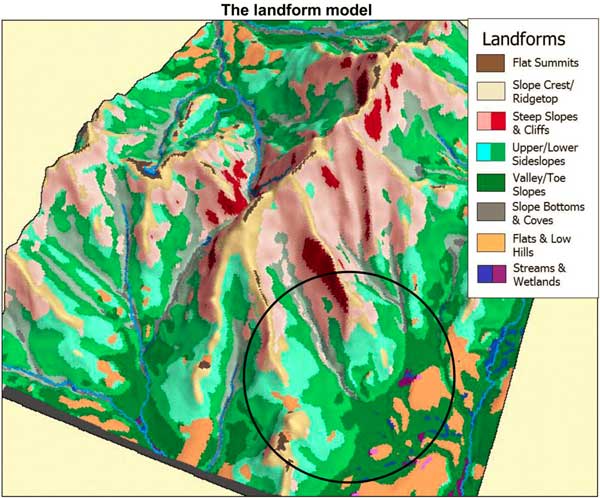

One such place, for example, might have moist valley bottoms next to warm and dry toe slopes, next to cooler and sunnier southwest-facing hill slopes. Plants and animals most attuned to temperature might move upslope, while those keyed to moisture might seek out bottomlands. The region continues to support high levels of biodiversity — though the combinations might be different.

Conservation has traditionally targeted places like granite mountaintops and headwater streams that harbor many rare species, says Anderson. There’s also rich biodiversity in many lower elevations landscapes on rich limestone soils, gently sloping sandy ecosystems and floodplains — but fewer have been protected because these locations (often sites of farms and urban development) are also expensive to purchase. The “flexible” approach puts the focus back on those landscapes and how to improve the odds for their species, too. “We’ll have to work with people to retain and restore a lot of the biodiversity in those places,” Anderson says.

Join the Discussion