California’s Channel Islands — the soaring vistas, unique species, productive waters and rich cultural sites — are the product of fortuitous location and continuous change. Parsing just how much of that change is due to modern human influence may hold a key to the long-term success of one of the Islands’ endemic species — the island scrub-jay. The situation could also serve as a test case for the complex choices that conservation will face as climate change compounds the effects of other human activities.

When Did the Scrub-jay Die Out on Santa Rosa?

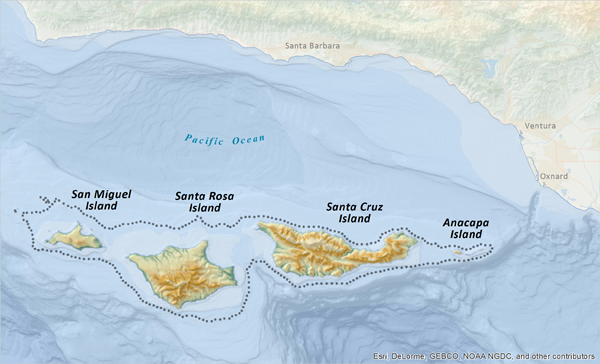

The jay’s current range is limited to the 250 square kilometers of Santa Cruz Island, one of four northern islands in the archipelago that formed a single land mass (Santarosae Island) during the last ice age. Santa Cruz supports a healthy population of jays now, but their range is far smaller than it was roughly 10,000 years ago when sea levels were lower and Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, San Miguel and Anacapa islands were all one island.

Even when healthy, such geographically-limited populations are vulnerable to climate change, disease, and genetic isolation. Re-establishing a second population of jays on neighboring Santa Rosa Island — which has a slightly different climate — could provide extra insurance against such risks and uncertainties. And the birds’ habit of caching seeds could offer some help in re-establishing the oak and pine forests that dominated the island before settlers introduced domestic animal grazing in the 1800’s.

Translocations of species can be tricky, and the National Park Service, which manages Santa Rosa and most of the other islands, relies on its establishing legislation — the Organic Act of 1916 — for guidance on management goals.

If the birds were wiped out on Santa Rosa during recent Western settlement, Park Service policy would likely favor reintroduction. On the other hand, if they died out before Europeans arrived, it could be said that – based on Park Service policy – the jays don’t belong there.

Evidence, but No Certainty

The historical clues are scattered and incomplete, so telling just when the jay disappeared from neighboring islands starts to look like a job for the CSI detectives. A recent paper in the George Wright Forum by Scott Morrison, the Conservancy’s director of conservation science in California, gathers many threads of evidence — from archaeology and historical ecology to genetics — and tries to connect the dots.

Genetic evidence suggests that the island scrub-jay diverged from its closest cousin — the mainland western scrub-jay — about a million years ago. So it must have inhabited the combined Santarosae Island during the last ice age. Jay bones dating to less than 1000 years ago have recently been discovered on neighboring San Miguel Island, suggesting a wider distribution of the birds in more recent history.

Several dramatic changes of the ranching era in the 1800’s could have driven the local extinction. Introduced sheep devoured the vegetation that jays need for habitat. Early visitors noted large flocks of ravens on the islands, surely supported by the abundance of sheep. One journal described in gory detail how the the ravens pecked the eyes of the sheep and scavenged carcasses.

Ravens also eat the eggs and nestlings of jays, so a large population of ravens would have put pressure on the scrub-jay population. In that era, Californians also shot jays for sport.

Perhaps the single most convincing clue in the case is a second hand mention of the jays in the field notes of Smithsonian ornithologist Clark Streator, who visited Santa Rosa Island in 1892.

It’s a fascinating bit of detective work, but in the end, there is no cathartic denouement in which the killer confesses. Rather, managers are left to weigh the uncertainties of the past against the uncertainties of the future.

How and When to Decide?

No one can say for certain whether the scrub-jay population of Santa Rosa died out thousands of years ago due to shifts in climate or 150 years ago from the impacts of ranching. And no one can say conclusively that reestablishing a population on Santa Rosa Island will provide much insurance against climate exacerbated extinction risks, such as habitat change and the spread of temperature-dependent diseases like West Nile Virus.

But Morrison’s paper points out that not acting is as much a choice as acting, and lays out the risks of each course and a rationale for deciding when to act in the face of uncertainty. He suggests that the relative simplicity of the question of what to do about this species could help managers develop a template for making decisions in the surely more complex decisions to come around the world, as climates, ecosystems, and conservation policies inevitably change.

Morrison feels the weight of history in these decisions. “We have to make sure these things don’t blink out on our watch,” he says. “And we need to think about what we can set in motion today to help the conservation managers of the future succeed.”

“We know from the recent extinction crisis of island foxes how quickly things can go bad for endemic species on these islands. Definitely has me looking for ways we can be proactive with the jay.”

The question of whether to translocate island scrub-jays brings into sharp focus questions about how managers evaluate risk, uncertainty, and urgency when making decisions. And in addressing those questions, managers will need to examine the philosophical and policy underpinnings of their decisions.

What is “natural” in an era of global warming? What should the management goals be of our National Parks and other conservation protected areas?

In the end, the mystery of when or why jays went extinct on Santa Rosa Island may never be solved. How managers proceed in the face of that uncertainty will be an early case study in decision making in this era of unprecedented global change.

I spent a week on Santa Rosa Island last year with the Sierra Club helping on an oak restoration project and heard about this controversy. Recently, I have been watching my local jays fly around and plant acorns at a good rate. I just can’t help thinking that overall the oak population would increase with the reintroduction of the jay on Santa Rosa and even San Miguel Island. I think the jays have a unique view of where to stash acorns that humans cannot replicate.