A stunning photo is making the rounds on the web of a snowy owl nest wreathed by 70+ lemmings.

The picture tells the story of rich times for one snowy owl; it had so much prey at its disposal that it couldn’t stop itself killing more rodents than it could eat.

This picture presents a hypothesis for this winter’s snowy owl invasion.

Here’s the idea: a superabundance of lemmings occurring in summer 2013 during the owls’ nesting season resulted in high nesting success. No baby owls went hungry and a superabundance of owls fledged.

Seeking to space themselves out, many of these young, well-fed owls are now invading unusually southern latitudes throughout North America.

At this point, we can’t be sure what has brought all of these owls south, but we do know that lemmings play a critical role in influencing snowy owl breeding distribution and nesting success. Beyond their role in the lives of owls, lemmings influence almost all aspects of arctic ecosystems.

![Lemmings influence almost all aspects of arctic ecosystems. Photo © User:CambridgeBayWeather or [1] (Own work) GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons](https://blog.nature.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/North_American_Brown_Lemming.jpg)

Scientists keep coming back to study these rodents because the causes of lemming population cycles are still not entirely understood. There are two competing hypotheses.

The first is that predators drive lemming cycles. Fox, skua, and snowy owl populations increase as lemming prey increases. At some point in time, the lemmings get overrun by predators and the lemming population crashes.

Shortly thereafter, populations of empty-bellied predators crash due to the dearth of lemmings.

The second hypothesis is that the lemmings cause their own misfortune. When populations of lemmings increase to high levels, they deplete their own food resources. They overgraze the moss and grasses that form their main diet, which then leads to a population crash.

Beyond their role in the lives of owls, lemmings influence almost all aspects of arctic ecosystems.

Joe Smith

Scientists can’t agree on which of these hypotheses is correct – or for that matter, whether both factors may play a role. Although the ultimate explanation for lemming cycles is elusive, their impact on arctic wildlife is profound.

Lemming cycles influence species that aren’t even lemming predators. For example, it’s been well established that shorebirds suffer higher rates of egg predation and nest failure in low lemming years as foxes and other predators shift from lemming hunting to nest finding.[1]

Geese respond to low lemming conditions by moving their nests adjacent to snowy owl nests. Talon-brandishing owls keep the area clear of nest-robbing foxes. The geese benefit from the snowy owl’s defense of its own nest.[2]

Just as these fascinating ecological relationships are being revealed, climate change appears to be influencing population cycles of arctic wildlife.

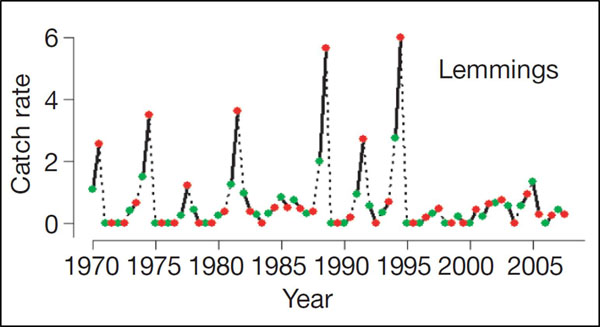

In Norway, lemming population cycles have flattened out since the mid-1990s.

The corresponding cycles of bird reproductive success have also flattened out. And populations of arctic foxes and snowy owls in Norway have declined dramatically. Predator declines are likely due to the lack of dramatic peaks of lemming abundance.[3]

There’s strong evidence that the condition of snow cover is causing the flattening of lemming cycles in Norway. Lemmings conduct a lot of business under the snow – from feeding on mosses to reproducing.

Warmer and more humid weather has created wetter, less crusty under-snow habitat conditions for lemmings that prevent them from flourishing.

On the other hand in the Canadian high Arctic, the domain of our North American snowy owls, lemming cycles remain intact and robust. Researchers predict a trend of increasing snow depth in this region as a result of climate change that will benefit lemming populations.[4]

Time will tell if climate change is playing a role in the recent snowy owl boom in North America.

The Arctic is a big place, and it is clear that conditions for lemmings in some parts of the Arctic remain prime or are getting better, making good times for snowy owls and bird watchers alike.

Join the Discussion

18 comments