On Prince of Wales Island in Alaska, the restoration of rivers goes hand-in-hand with the restoration of cultural traditions.

I’m having lunch with members of the Hydaburg Cooperative Association, a federally recognized indigenous tribe, following a morning of collecting data for stream assessments (covered in detail in yesterday’s blog). Haida community members were trained in ecological monitoring protocol so they could restore streams important for their community’s food and culture.

We sit along the stream eating venison sandwiches and salmon spread, discussing the science. Tony Christianson, the enthusiastic thirty-something mayor of Hydaburg and head of the community’s natural resources program, waves me over to his car. “I want to show you something,” he says. “You can’t understand what we’re trying to do on the streams without seeing what else is happening in our community.”

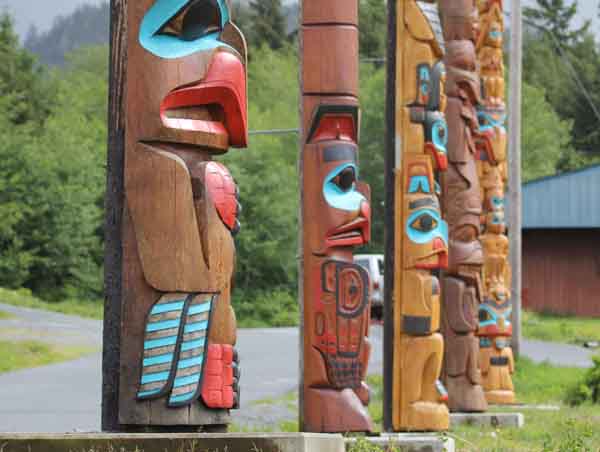

Christianson drives me to a building that has become a center of Hydaburg cultural life. As we walk inside, the smell of cedar fills the air as men quietly carve, chip and shape totem poles. “We are the people of the salmon and the people of the cedar,” explains Christianson. “We spent all spring and summer putting up salmon. The rest of the year, we carved.”

Intense logging and other habitat degradation seriously affected the salmon, but the fish still provide for the Haida. The story of totem pole carving is one of even greater loss—and restoration.

“There Was a Great Void”

Totem pole carving was long an important tradition for the Haida, a way of passing on stories of the world and how to behave in it. But in the 1930’s, the U.S. government made totem pole carving and other Haida traditions illegal.

“They believed that to save the man you had to kill the Indian in him,” says Terrance “Hagoo” Peele, Tony’s father and today an active carver. “They believed that tradition is the enemy. They ended our traditions and made us Safeway Indians. There was a great void.”

The prohibition on totem pole carving was lifted in 1962; by that time, though, the traditional knowledge behind it had been largely lost. Hydaburg’s totem park—a collection of poles in the center of town– had not had a new totem pole since 1938.

Another community of Prince of Wales Island, Klawock, had a similar story. But 22 years ago, a teacher named Jonathan Rowan decided to enlist his students in restoring the totem pole carving tradition. Hydaburg community members suggested I visit Rowan’s shop to see what was happening there.

It’s abuzz with activity: students and others hurry around, moving logs, carving them, painting them. At the center is Rowan, a thick-armed former Marine who calls out orders as he carves.

“Look at this,” he says, pointing around. “This place is hopping right now. We have poles being carved. We have poles being painted. It’s awesome.”

When Rowan was young, the Tlingit people in his community were carving on a smaller scale – items like halibut hooks, masks, and paddles – but totem pole carving had mostly disappeared. The village hired a Tlingit carver from outside when it wanted to carve the first new pole in recent memory. That was now more than two decades ago.

“I’m not a touchy feely guy, but when I wake up at four in the morning, I’m thinking of making something,” he says. “I need to be creating something. From the time I was a kid, I wanted to do this.”

The Klawock totem pole carving tradition was revived when the city, the school, the U.S. Forest Service, the Sealaska Corporation and the Klawock Heenya Corporation all worked together on creating totem poles for the community’s totem park. “For me, it’s important that this is passed down,” says Rowan. “The carving tradition was almost lost. We can’t lose it again. We put our kids to work doing this, so they have ownership in our traditions.”

I meet one of those students in a quiet shed, where she sits alone, painting the totem poles. Sydney Isaacs, a cheery college student attending the Institute for American Indian Arts in New Mexico, has been painting all the totem poles that have been carved this summer.

“This is a real privilege, a very high place to be,” she says. “I grew up knowing the important stuff of our community, stories about our ancestors and our traditions. And now I’m playing such a role in it.”

“We are Haida”

Back in Hydaburg, Tony Christianson says he had long noticed and even envied the work Rowan was doing in Klawock. Eight years ago, Christianson’s brother was killed in a logging accident. In his grief, he turned to carving a totem pole.

“That was the first pole raised in Hydaburg since 1938,” he says.

Christianson frequently mentions forces of nature: streams and oceans and deer and salmon. Strolling through Hydaburg, it’s apparent that he is actually a force of nature himself. Kids run up to him, calling him “uncle.” Community members stop to talk about plans for the stream assessment and salmon fishing.

He has been part of the Hydaburg tribe’s initiative to create a week-long culture camp, a celebration of Haida traditions including totem carving, canoe making, potlatches and wild food harvesting. And totem carving is flourishing.

“For years, the government made our traditions a source of shame and fear,” says Hagoo. “Today, we recognize that we need our traditions and our traditional foods to make our minds and bodies healthy again.”

Christianson sees the scientific stream assessment and restoration of traditions like totem pole carving as two parts of the same effort. “The environment is constantly changing. The community is always changing. We recognize that,” he says. “We need science to show us how to restore our streams. But we also need our traditional knowledge to restore our pride.”

Before we leave the carving shed, Hagoo shares several traditional songs, songs of loss and love and history. As he sings a song remembering his ancestors, tears stream down his face as the memories of loved ones come back. He sings another song to send their memories back. As he tells me the meanings of each of these songs, his eyes fill with tears again—this time with pride.

“This carving, this work that is happening here, is helping us heal,” says Hagoo. “Everyone should know who they are and where they come from and be proud of it. We want to hold up our heads and say “We are Haida.”

My wife Elora & I, Monte McKenzie, taught school two years in Hydaberg just before the turn of the century , Peals & a few others were then carving in a building next to the town dock that housed the old fish canning facility built by the government but never used! everyone in that villiage will remember ,us if they were in school then! Ray Sanderson, if he is still alive was my very good friend and Elora had several good friend’s amoung the “elder” women who are the real tribal leaders ! Elora’s and my students would now be in their 40;s and more , I was just turning 65 and decided to retire so said goodby and came home ,to our mountain home in WV .

While Super of schools in Hiadburg and Pelican AK i had the wounderful opportunity to carve on totem poles,put them and be apart of the activities. I am thankful for that and just being able to live in the community. Always be a part of me in the two towns. Thank you.

From the stories I’ve heard told by our grandfathers , uncles and our father the missionaries thought we were worshipping the totem poles . They did not understand that it told a story of a person or important event that happened , memorarl poles . Kake elders had many meetings , very emotional time to decide to move into the whitemans world to become civilized , at which point they decided to burn the totems . To mark this major event a golden spike was driven into a board walk that was being built at that time it ment we were westernized . Kake had a totem pole billed as the tallest totem in the world , it was taken to the worlds fair in japan . Then brought home to Kake to be put up in 1972 , there was a three day long potluck in celebration of this major event . People from many villiages came , there was dancing and singing old regalia never seen for years were brought out . Our brother Norman Jackson was one of the ones to start carving working to bring back our art .

As was customary to our American culture. We found it neccesary to discourage native customs and their heritage. After all how can one become vital to the American economy if all they can do is follow their traditional customs and ceremonies.A visitor to Alaska would be unable to carry a totem pole into the lower 48 for any number of reasons. Therefore our government would discourage such a waste of the native peoples time and encourage them to make something we could carry back in our pocket or suitcase. the assimilation of native peoples all over our world suffer discrimination, hopefully we will become more aware of their given rights in all nations, and allow them the freedom to express their heritage.

Hi Ingrid,

According to tribal elders, tribal members were forbidden to carve totem poles until the early 1960s. It can be difficult to track down specific laws for a number of reasons. In Hydaburg, carving was clearly not a souvenir business — the carving tradition completely died, until Tony Christianson led the revitalization effort. There are a number of excellent books on the overt and covert efforts to “assimilate” Native Peoples and what that meant for their culture, traditions and health.

In this article you mention that the US made totem pole carving illegal in the 1930s. I found that interesting and wanted to know why they would make the tradition illegal, but in my research I did not find anything saying it actually was. All I found was that Canada made it illegal from the 1800s through 1951. I also found that in the 1930s the United States made a greater effort of expanding Native American Art but, through that process, made carving less of a tradition and more of a souvenir business.

So, was it actually illegal in the US? And if so, why?

Matt, in early June, 2009 while we were working on the Prince of Wales Watershed restoration projects Katy and I visited with the Totem Pole carvers in Hydaburg and took several photos. Some of these have the old Totem Pole they are copying next to a new one.

We did not have much time that day and afterward I thought we should have videotaped some of the work being done. Possibly they have created videos like this to demonstrate the creative process.

Thanks for the article.