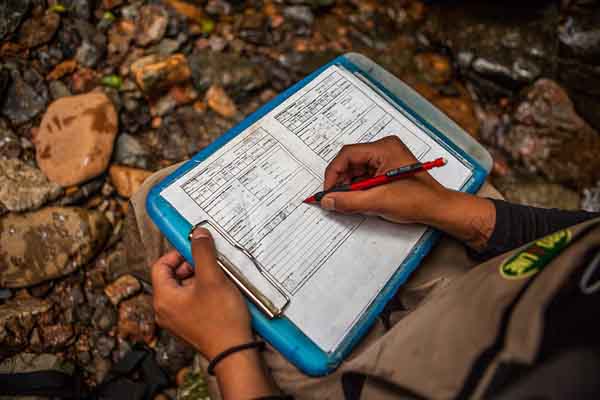

Rain soaks their hair, splatters their glasses, runs down their collars, but Herbert Nix and Tony Sanderson hardly seem to notice. They’re busy recording data: stream flow, gravel size, water temperature, habitat conditions and salmon spawning sites.

I struggle along to keep up as they call out numbers to each other; the thick, soaking brush causes me to slip and fall frequently. Not them: they leap over rocks, ford streams and shimmy along slick fallen logs as if they’ve been doing this their whole lives. Because they have.

They know these streams intimately, return to them each year to catch the salmon and steelhead trout that will feed their families. They hunt deer and collect firewood in the thick forest. They dig clams and set crab pots in the estuaries, collect herring eggs and harvest sea cucumbers. But today they’re practicing new skills in this familiar environment.

In short, they’re becoming scientists.

Nix and Sanderson are members of the Hydaburg Cooperative Association, a federally recognized indigenous tribe found on Prince of Wales Island in southeast Alaska. They’re participating in a project with The Nature Conservancy to assess and monitor salmon spawning streams. The data they collect will help better protect the resources that the Haida—as the community is known–rely on for food and cultural traditions, and direct stewardship and restoration activities. Their goal is to use data to get these streams protected under Alaska law; streams that provide proof as good salmon habitat can be protected at the highest level by the state.

“We’re taking our traditional knowledge and integrating it with Western science, and putting people to work in the process,” says Anthony Christianson, natural resource director and mayor of Hydaburg. “Everybody wins here.”

Several years ago, Christianson says the community recognized the need to better assess and monitor the streams that provided so much. In decades past, logging had provided no buffers around streams leading to some degradation of conditions. Community members recognized the need to better protect and restore streams to sustain the salmon and other resources for future generations.

It turns out, The Nature Conservancy had very similar goals for Prince of Wales Island.

Thus, a partnership was born to protect and restore streams important for salmon and the Haida community. First, streams had to be assessed. With their extensive knowledge of the stream, community members were obvious choices for the work. They just needed to learn the science.

“We wanted actual concrete projects to make a difference for streams,” says Christianson. “And we wanted to build local capacity so that the community could lead stream restoration efforts.”

Last year, several community members including Dix, Sanderson and Minnie Kadake took a class in stream monitoring followed by in-stream practice. After a brief refresher, they’re ready to begin monitoring. I’m joining them on their first day in the field recording data.

Cathy Needham of Kai Environmental in Juneau taught the class, and is joining the field technicians today to make sure they have mastered all the skills. As we head down the first stream, they’re mapping it with a GPS unit while recording a dizzying array of stream characteristics: water temperature, fish species captured in traps, channel width, stream gradient, substrate characteristics (including rocks, sand and debris) and the presence of potential obstructions like bridges and road culverts.

Along the way, Needham stops frequently to quiz Nix and Sanderson, as well as several interns assisting with the project. “Is this a braid or side channel?” she’ll ask, or “Who’s going to teach others about gradient?”

They carry what they call “cheat sheets” to remember key stream characteristics. They’re following Alaska Department of Fish and Game protocol for stream assessment, which will allow them to better make the case for stream protection and restoration. They will also have baseline data to assess future threats. The goal for the summer is to completely map and assess five key salmon streams used by the Haida community.

“The goal here is to have the community run the project,” says Needham. “There are definite restoration needs. The data collected will direct those efforts.”

For Nix, learning the science is a natural extension of his life in the streams, estuaries and woods. “Just this past weekend, I’ve caught abalone, shrimp, ling cod, red snapper, sea cucumber, seaweed and gumboots. I’ve set hemlock branches where herring will lay eggs, and then I’ll return and collect the eggs. I have gallons of salmonberries and blueberries,” he says. “This is where I get my food. It provides for me. Learning the science came naturally.”

Christianson believes this is part of a larger effort to restore not only the environment, but also pride in the community’s self sufficiency and traditional knowledge.

“This stream assessment work is not just a job,” he says. “The people working on the stream share what they learn about ecology and stream conditions with their families. Everyone is already connected to these streams through food and tradition. Now they are also become more environmentally connected so we can ensure that these streams provide for our children and grandchildren.”

I’m so glad you people are looking out for our salmon,waters,land! We need protection against polluters! Thanks for all you do! Sincerely, Melissa VerDuin

Awesome post…great to see scientists and local communities work together in a balanced and respectful way. Are there specific local threats that have effected the salmon population? Or is this one of the first stream assessments done in the area?