A Collaborative Study with the Insurance Industry

Four years ago this month, Hurricane Sandy devastated much of the US Atlantic coastline. A few weeks ago, Hurricane Matthew caused widespread flooding from Florida to North Carolina and across the Caribbean.

I follow hurricanes with concern and interest: concern for those in their path and interest as an engineer working in the interface between flood risk mitigation and nature conservation. When I tell someone that my work involves understanding if ecosystems like wetlands can protect us from storms, I usually get asked, “Sure, but by how much?”

Awareness of the role of coastal habitats in risk reduction is growing. The Indian Ocean Tsunami in 2004, Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Hurricane Sandy in 2012, Typhoon Haiyan in 2013: after each of these extreme events, there were a number of stories of how wetlands, reefs and dunes reduced the risk of flooding in specific places and communities.

As it turns out, actually quantifying the value of these natural defenses is not easy. Unless we are able to consistently value their risk reduction benefits it will be difficult to translate all this attention into action for conserving and restoring threatened habitats.

Valuing Risk Reduction Benefits

To value the risk reduction benefits of coastal wetlands we need to estimate two related aspects of flood risk: 1) the physical effect of wetlands in reducing flooding and; 2) their economic effect in reducing property damages.

Over the past 50 years, scientists have shown that coastal habitats are very good at reducing wave energy. Using measurements and models a start has also been made in quantifying the extent to which they reduce flooding. The missing link is translating these to reductions in property damages.

We examine the value of temperate coastal wetlands in reducing property damages during hurricanes in a new report and research project “Coastal Wetland and Flood Damage Reduction” funded by the Lloyd’s Tercentenary Research Foundation. Initiated by the Science for Nature and People Partnership Coastal Defenses Working Group, this work combines state-of-art flood risk modelling and ecological expertise to assess how much temperate coastal wetlands reduced flooding and property damages during Hurricane Sandy and other storms.

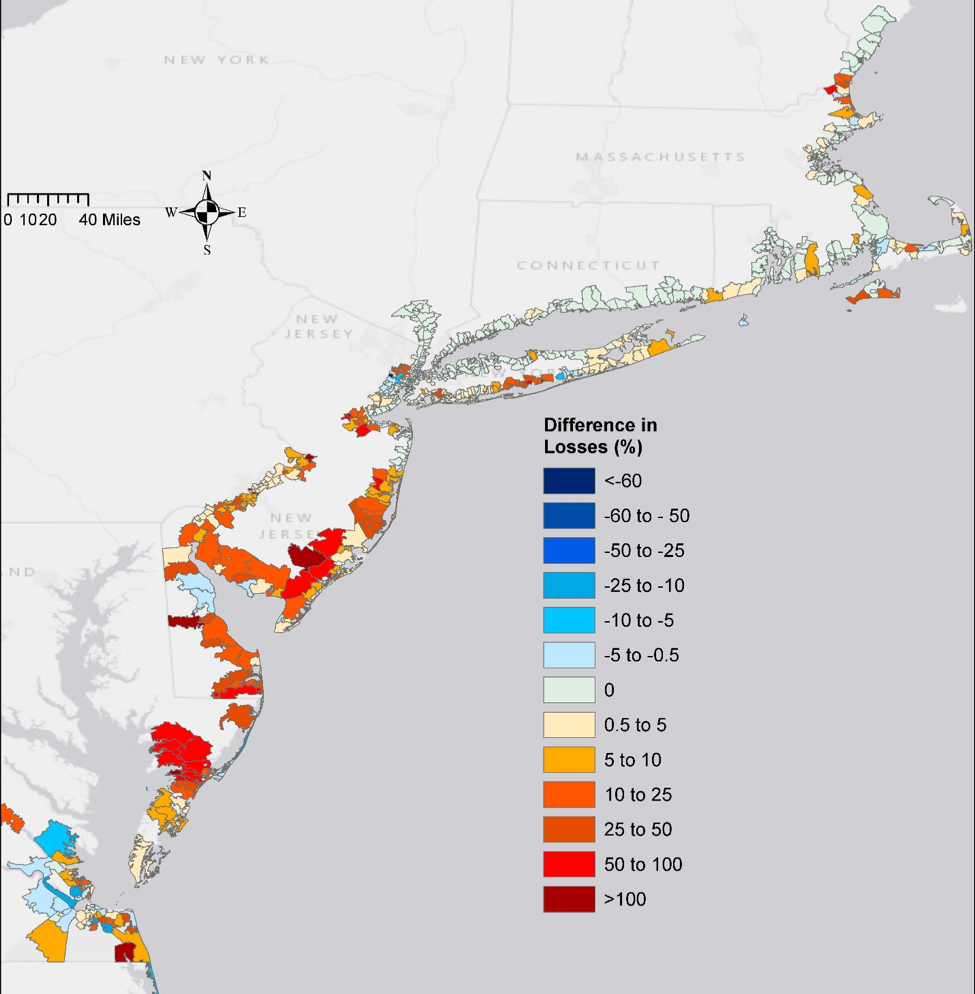

We assess flooding and property damages from Hurricane Sandy for two scenarios: 1) with wetlands present as they are today, and 2) if all these wetlands had been lost to open water.

In total, coastal wetlands were estimated to have saved $625 Million in flood damages during Sandy. Wetlands reduced flood damages to properties by 10 percent on average in the areas where they remain.

Coastal wetlands are estimated to have saved $625 million in flood damages during Hurricane Sandy.

@SidNarayanMA

We also find considerable spatial variation in the extent to which coastal wetlands reduced damages. For instance, in Maryland which had a lot of wetlands and relatively low flooding, wetlands reduced damages by 30 percent. New Jersey – where Sandy made landfall – had the highest flood damages and also, the townships with the highest absolute savings from wetlands.

Hamilton Township in New Jersey, at the upstream end of an estuary, is an example of the cumulative benefits that wetlands have in protecting properties. Though Hamilton itself has very few wetlands, damages to properties in this township would have more than doubled if wetlands further downstream had been lost.

Can Wetlands Provide Protection on a Long-Term Basis?

But Hurricane Sandy is one event. We also wanted to know if wetlands can provide protection on a long-term basis, against storms of varying intensities. We examined if salt marshes could reduce annual expected property damages – a standard industry metric for risk – in Ocean County, New Jersey.

We identified areas on the shoreline that still have marshes, next to areas where marshes have been lost to development. We analyzed 2000 storms to see if annual flood losses were affected by whether the properties had a salt marsh in front.

Surprisingly, we found the average reduction in annual expected damages due to marshes was more than 20 percent. This is a significant proportion on a highly vulnerable coastline, where rising sea levels and coastal development continue to threaten the marshes that form a first line of defense. This effect was more pronounced at or near sea level – i.e., in the riskiest areas.

These findings have important implications for private and public risk management practice. Governments – both local and national, should actively consider the risk reduction value of these habitats when funding coastal management or conservation projects and when deciding where to allow development. Private industry – particularly the risk industry – should account for this value when deciding where and how to manage risk.

The most important take-away for all of us involved in this work has been the realization that it is indeed possible – by combining expertise and tools from insurance, conservation and engineering – to place a value on the risk reduction services of coastal habitats and, ultimately, to incentivize the conservation of these habitats for coastal resilience.

Join the Discussion