Each fall and winter, California’s Central Valley supports millions of birds stopping to rest and feed during their long migration from Canada and Alaska to Mexico and back again.

With 95% of the valley’s historic wetlands converted to cities as well as rice, corn, alfalfa and other forms of agriculture, migratory birds traveling along this Pacific Flyway face a major habitat deficit each winter.

Purchasing the nearly million acres of habitat that scientists estimate is needed by these birds would literally cost billions of dollars.

How can conservationists protect this much habitat in a highly productive agricultural region where permanent protection is so expensive? A market-based approach that pays farmers to create wetland habitat temporarily for a few weeks per year offers an innovative answer.

During the program pilot this past winter, BirdReturns paid rice farmers to create “pop-up” wetlands by flooding their rice fields during February and March, which is when the habitat deficit is greatest.

Due to air quality regulations in California, most rice farmers flood their fields during the middle winter months in order to decompose the straw residue left over after harvest.

In a typical year, rice farmers drain their fields at the end of January, at the end of duck hunting season. Yet birds are migrating through the valley well past that date.

In the pilot, 33 rice farmers in California’s Central Valley created nearly 10,000 acres of wetland habitat. The price tag: several hundred thousand dollars total, a tiny fraction of the estimated $65 – 100 million that permanent protection would have cost. At these prices, BirdReturns could run for hundreds of years and still cost less than purchasing the land.

The citizen science necessary for BirdReturns has been well covered in mainstream media. The economic aspect of this program has not been covered in as much detail, but it is a critical element that allows conservationists to take the program to a landscape scale.

Here’s how it works. First, Conservancy scientists developed detailed maps of the gap between bird needs and habitat availability.

To make these maps, the Conservancy used crowdsourced data from eBird, an application developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the National Audubon Society. Amateur birders around the world have shared some 187 million observations in eBird, and data scientists at Cornell use this data to create predictive models of exactly when and where birds fly during their migration.

Conservancy scientists coupled the information about bird migration patterns with data on water availability developed in collaboration with Point Blue Conservation Science to estimate the locations and timing of greatest habitat need.

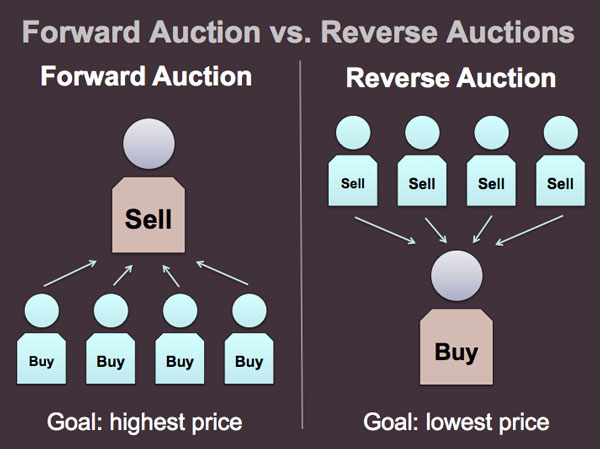

Next, the Conservancy used a reverse auction to have rice farmers bid on how much the Conservancy would have to pay them per acre to flood their fields with a couple of inches of water during the critical winter period.

In a reverse auction, a buyer seeks to get the lowest possible price by having potential sellers compete against each other to bid prices down.

Think of a reverse auction as similar to when a homeowner solicits multiple bids for work from contractors. The homeowner puts together a scope of work, solicit bids, and chooses a contractor based on some combination of factors including price and quality.

Finally, based on estimates of the amount of habitat needed and the pricing of bids, BirdReturns accepted up to 80 percent of the bids. Each farmer received the price they bid. Just as with the contracting example, the lowest price didn’t always win, but it was a key criteria.

Farmer’s bids varied based on factors such as water cost, soil conditions, labor costs associated with creating the temporary habitat, and economic risks the program might create like not being able to plant on time in the spring.

BirdReturns has many advantages over conservation programs that set a single, uniform price for all farmers.

If the price is too low, there will be insufficient demand and too few farmers will sign up for the program. If the price is too high, there will be an excess of demand and the government will over-pay. In a time of huge societal needs and competing demands for scarce public dollars, such over-payment means that other valuable programs are not being funded.

In a reverse auction, the farmer sets the price, a price based on producing habitat. Farmers understand this intuitively. It is how they work, how they get paid for producing crops.

As one farmer put it at one of the Conservancy’s initial meetings: “You want us to grow birds, like we grow rice. We know how to do that.”

Yes, that’s it exactly.

Preliminary results from the pilot year are very promising. Flooded rice fields in February and March have 30-50 times more shorebirds than experimental control sites. For dunlin, a small bird that breeds in the Artic that can be thought of as an indicator species, BirdReturn fields in March provided habitat for an estimated 20% of birds in the entire Valley.

BirdReturns’ approach to sourcing habitat allows a great deal of flexibility and adaptability; it doesn’t commit conservationists to owning a property in perpetuity.

Add to this the simple fact that the whole system is dynamic.

Differences in weather, market conditions and many other factors mean that the migration routes and the location of bird-friendly farmland shift. So, habitat acquired or permanently protected through a conservation easement may not be as important from one year to the next.

A reverse auction, coupled with nearly real time data on when and where birds need habitat, gives us an adaptive management tool suited to the system.

Think of it as if you’re traveling to a new city for a couple of weeks. You don’t buy a house; you rent a hotel room.

Birds similarly need only a couple of weeks of appropriate habitat. So, why purchase permanent and expensive habitat protection when all we need is to rent habitat for a few weeks a year?

It’s an economical approach to conservation, allowing our members’ donations to go farther and be more effective. It’s also a great way to partner with farmers who may not want to permanently commit to using their farmland for conservation.

Due to the flexibility of the reverse auction tool, we can adjust the program to reflect changes in agriculture and migrations. And if we do get something wrong, it is only temporary – it is very different than purchasing the wrong property.

We believe this is an evolution of working lands conservation, an increasing area of focus among conservationists as we recognize the need for wildlife to coexist in a human-dominated world.

Could this reverse auction have other applications?

It could be used by commercial fishers to set the price for selling outdated fishing technology, could be used to pay farmers for riparian conservation that benefits salmon that temporarily use a stream for spawning, or even for in-stream flows for part of a year.

The results show that renting can be a highly effective conservation tactic to complement permanently protected areas that already exist in most landscapes. BirdReturns is that rare win for both birds and farmers. And for conservationists too: it allows us to use precious donation dollars in the most efficient way possible.

This is a fascinating concept. I read the article in the New York Times and wanted to research it further. As director of a small land trust working along two significant watersheds for anadromous steelhead habitat, I’m very interested in the concept of “renting” creek habitat. We also are engaged in protecting a rare Monterey pine forest and I’m thinking of ways to apply this concept for privately owned forest lots as well. Thank you for the work you’re doing–please let me know if you have any public workshops or symposia on this topic.

Great work, especially in an area where shorebird habitat is under intense pressure for development and agricultural uses, and water is so valuable! Your “reverse auction” is certainly a cost effective method to acheive critical habitat goals. It is a “win-win” for the farmer and the birds.

FYI, in the Misissippi River Valley, some rice farmers keep fields flooded all winter until planting. They actually drop the seed from airplanes into the shallow water and drain the field within 24 hours. There are no weeds and soil moisture is high so the rice germinates very rapidly with little competition. We actually did this at St. Catherine Creek NWR, a refuge that I managed for 6 years. Other than pumping costs, this was a very cost effective crop to grow.

Earlier in my career, I worked as a Private Lands Biologist, also with the FWS. To promote winter flooding of rice fields for ducks, I worked with Preston Sulivan, who was working with Appropriate Technology for Rural Areas, to interview rice farmers in Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana to ask them to identify the benefits of over winter flooding. In addition to rotting straw mentioned in your article, weed control and soil moisture mentioned above, private landowners also reported significant profits from leasing and/or selling duck hunting and crawfish. Our work was published in the April 1993 Rice Farming magazine. The title got twisted a bit to “Precision-Leveled Fields Prove Excellent Long-Term Investments.” The information gained from the farmers proved to be quite valuable in our effort to promote winter flooding for waterfowl.

I know that shorebirds prefer very shallow water to mud flat habitat. Weeds will germinate in the exposed soil thereby reducing some of the cost savings of over winter flooding. My point here is that extending the flood period to provide critical shorebird habitat may be providing significant incidental benefits to the farmer. I encourage you to document these benefits as they may be a valuable asset to promote your program.

Keep up the great work!!!

Bob Strader