To imagine the life of a freshwater mussel living in a southeastern U.S. river, picture a couch potato with a constant buffet line rolling past.

Anchored along the river’s bottom, this freshwater shellfish simply filters the water as it drifts by, getting its meals from the current.

For certain people, this may sound idyllic.

But the permanently sedentary lifestyle presents certain obvious problems: It’s kind of hard to hook up with another mussel when you don’t move. And it’s even harder to get the kids out of the house.

Still, the mussel has a few tricks in its shell when it comes to love and empty nesting, evolved to take advantage of river currents and unsuspecting fish.

No-Touch Sex

When it comes to sex, mussels master long-distance relationships. In fact, no direct contact is required.

Male mussels simply eject their semen into the river’s current. A short distance downriver, the female — filtering water, as mussels do — collects the floating semen and fertilizes her eggs. Mission accomplished.

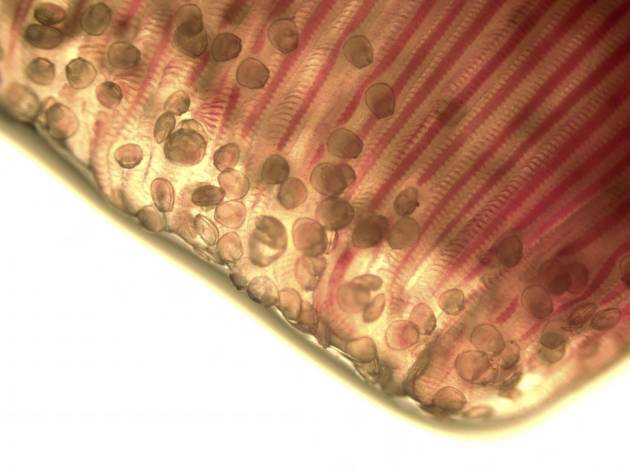

Microscopic young mussels then hatch inside the female mussel’s shell, a safe and nourishing environment.

They can’t stay there forever. The problem is, sans shells, the tiny little mussels are helpless against predators. How can they survive the cold, hard world river world around them?

Enter the world’s strangest fishing lure.

Scientists have only recently revealed a striking strategy for both dispersing and protecting young mussels in southeastern rivers like Florida’s Apalachicola.

There, certain species of mussels — like the strangely named shinyrayed pocketbook — stick out a lengthy fleshy protuberance into the river. In the current, it shakes and shimmies like an injured minnow. At the end of this 18-inch lure rests a sack filled with baby mussels.

Picture a bass, hunting along the river’s edge. It spots a minnow struggling. Perhaps it’s been fooled by a rubber worm or two used by area bass anglers, so it pauses for a second to warily eye its potential prey.

This is no fake.

The bass darts forward and gulps the minnow.

As it bites: an explosion.

The “minnow” disappears back into the mussel’s shell. The bass receives a mouthful of mussels.

The tiny mussels quickly attach themselves to the fish’s gills, where they’ll filter nutrients while living safely in the formidable castle of a full-sized fish.

When the mussel is mature enough to face river life, it releases from the gills, the fish none the worse for the experience. The mussel attaches to the bottom, having evaded many of its predators.

Why Fish Might Be the Mussels’ Meal Ticket

Unfortunately, the mussel faces other challenges for which it hasn’t had time to evolve solutions. Pollutants and altered river flows threaten many freshwater mussel species.

Most people, frankly, don’t care. Sure, mussels may be nature’s water purifiers. Conservationists call them a canary in the coal mine. Historically, a few people ate them. A few more made buttons with their shells.

Still, they’re not exactly charismatic.

Freshwater mussels are the kind of creatures that welcome scorn from those opposed to endangered species funding: Conservationists put the shinyrayed pocketbook ahead of people!

The road to mussel conservation funding and policy is thus littered with bitter debates and ridiculous sound bites. Some of us may argue that mussels — as irreplaceable and fascinating creatures of evolutionary history — deserve our appreciation, too. But that argument fails to persuade most.

However, the mussel’s strange underwater breeding life may hold an answer to its survival. Since the mussel needs fish, restoring fish could help restore mussels.

People like to catch and eat fish. They have a fan base.

On many rivers, a lot of the restoration efforts have focused on the benefits to native fish species. But restore habitat for fish, and you often restore it for mussels, too. And not only that, but mussels need specific native fish species to survive.

Science has only recently revealed the ways mussels attract fish, and use their gills to carry their young. That knowledge not only deepens our understanding of the natural world; it also likely leads to more effective — and uncontroversial — conservation.

This is a mind blowing Article! I can’t believe how much the water in Illinois River, Matanza Beach & Quiver Beach has changed in the last 35 years! We spent weekends on the Illinois River & At Quiver Beach, back then I was very young, But the water was so much cleaner back then! Then we moved into a house on Matanza Beach and at that time the lake was not connected to The Illinois River! It also was being fed by springs, if the water was low enough you could see the fresh water coming up from the beach making a path to the lake! We use to find mussels & some times just parts of shells!!

I enjoy learning something new everyday but this was extraordinarily interesting!

It just blows my mind how in nature one species can be so intricately connected to another.

Imagine, mother mussel sending her little ones to grow up in fishes’ gills. Right out of science fiction!

Our advanced technology, computer science and those fabulous electronic inventions have nothing on this mussel! And with all that, will they be capable of saving our planet? Boy, I hope so.

My eleven-year old grandson asked me if the planet will still be safe for his children. That child should not even have to ponder such a future……..

Matthew Miller, thank you for your excellent reporting on this “miraculous” biological feat.

Here in the Delaware Bay there is a project underway to raise large numbers of mussels and restore them to the river and the creeks of the Delaware River Estuary. In all the articles I’ve read about this in the newsletters of the involved organizations, I’ve never seen mention of the role fish play in the reproduction of the mussels.

If it is new knowledge, I’m sure it would be important for the success of the project which is based at the historic Water Works at the foot of the Philadelphia Museum of Art along the Schuykill River. I was planning to visit soon, now I have an important question to ask the exhibitors.

This is a great example of the importance of being a member of The Nature Conservancy. I recently became a sustaining member of the Conservancy. Every time the discouraging news about climate change gets me down there is always great information from The Nature Conservancy to buck me up,

especially because I am helping to make it happen by being a monthly sustaining member.

Thank you!

Hey Matthew,

That must be one heck of a bass to bite on an 18 inch lure. And how does the mussel stow such a massive appendage in its shell. Or was that supposed to be 18mm?

I really enjoy your posts. This one I’ll share with the kids.

Steve