“Sharks, not mankind, are the species in danger, the animals now being driven rapidly towards extinction.” – Sharks of The World (Compagno 2005)

There are more than 500 known species of sharks the world — most of them you’ve probably never heard of. In fact, almost 16 percent of all sharks are threatened with extinction (ranked as Vulnerable or higher by the IUCN).

Most of the ten critically endangered sharks became endangered (and in some cases may already be extinct) before they were well studied. They are now so rare that it is difficult to study them at all since both the sharks themselves and the funding to study them are hard to find.

As David Shiffman, a Liber Ero Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Simon Fraser University studying shark conservation, says in his Southern Fried Science article, “Increased public attention coupled with vocal public support is essential for advancing conservation policies. The shark species at the highest risk of extinction aren’t getting the attention they need, even from eco-friendly media that claims to be highlighting the shark species at the highest risk of extinction.”

Some Basic Facts About the Most Endangered Sharks

1. Pondicherry Shark (Carcharhinus hemiodon)

Habitat: Indo-Pacific; coastal waters and possibly the mouths of rivers

Max Size: 102 cm

Threats: All of the places where the museum specimens were originally caught now have large, unregulated fisheries.

Points of Interest: The species hasn’t been seen in five decades and may already be extinct. Nothing is known about the behavior of the Pondicherry shark and little is known about their biology. There is hope that these sharks are still hanging on – Rex Ian de Silva, a biologist specializing in sharks, reported a potential sighting from Sri Lanka in 2014. The photo was inconclusive – it could also have been a small bull shark. Sri Lanka is a priority for Lost Shark Guy Dave Ebert, who is searching for the Pondicherry and other little known or unknown-to-science species.

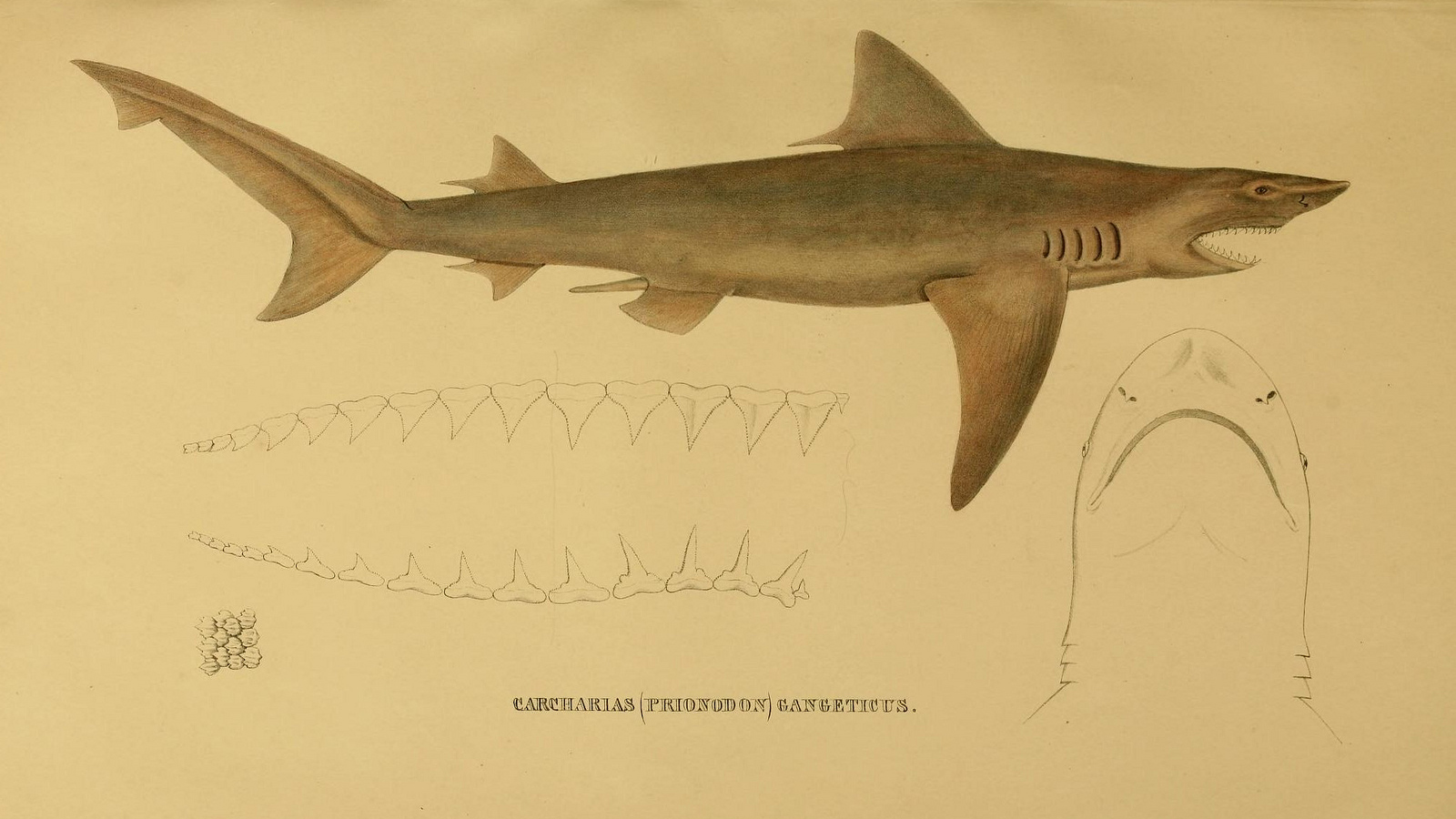

2. Ganges Shark (Glyphis gangeticus)

Habitat: Indo-west Pacific, unconfirmed reports as far west as Pakistan; rivers and recent reports from estuaries and on inshore continental shelves.

Max Size: At least 204 cm

Threats: Most confirmed reports are from a narrow area of habitat that is heavily fished and is impacted by increasing development, including dams. These sharks might find good habitat in the mangroves of the Sundarbans, but there have been no shark surveys there.

Points of Interest: The small eyes of the Ganges shark suggest that it swims along the bottom of the river in turbid water watching above for its prey. It has narrow teeth, often a feature of fish-eating species.

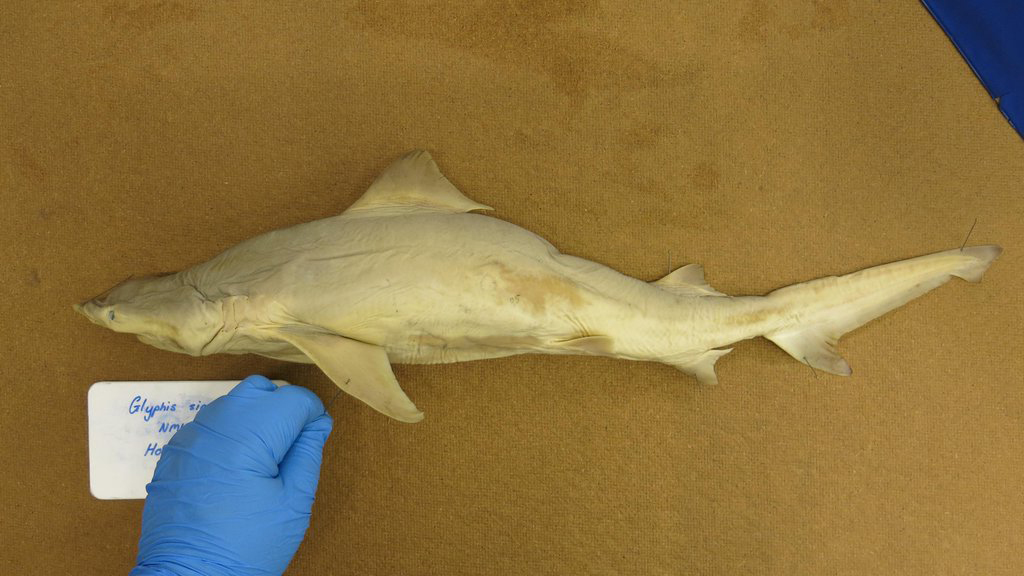

Recently found to be a juvenile Ganges Shark, not a separate species!

Habitat: This species was identified based on one 19th century museum specimen caught near the mouth of the Irrawaddy River in Myanmar. A recent DNA study showed that the Irrawaddy river shark is the same species as the Ganges shark.

Max Size: Irrawaddy specimen = 60 cm male.

Threats: If any Ganges sharks remain in the Irrawaddy, they are threatened by intense fishing – during surveys for Irrawaddy dolphins, 5,701 fishing gears were found in the river. There are some protected areas in the presumed range of these sharks within the Irrawaddy, but they currently lack the funding necessary for effective shark conservation.

Points of Interest: The change in species status highlights the difficulty of identifying sharks based on a small number of aging museum specimens. The identification of the specimen as a Ganges shark broadens the range of the Ganges shark in the Indo-Pacific. That’s good for conservation because it’s harder for widespread populations to be wiped out by one catastrophic event.

4. Northern or New Guinea River Shark (Glyphis garricki)

Habitat: Papua New Guinea to Northern Australia rivers, estuaries and seas

Max Size: Mature at around 200 cm, max length unknown

Threats: In Australia, Northern river sharks are taken as bycatch in commercial and recreational fisheries. The West Alligator River in Kakadu National Park is a refuge for newborns and small juveniles.

Points of Interest: Scientists tracking them in Australia have found that only pups and juveniles live in fresh water. The females swim upriver to give birth in October, before the monsoon season. Adults spend most of their time in tidal estuaries, highly turbid estuaries and seas. Northern river sharks are viviparous (give birth to live young) and can have up to nine pups. They have an unusual number of ampullae of Lorenzini (the organ that sharks use to sense electric fields) and likely use this sense rather than sight to find prey. (You can read more about The Nature Conservancy’s efforts to protect their habitat here.)

5. Happy Chappie or Natal Shyshark (Haploblepharus kistnasamyi)

Habitat: A an area of around 1,000 km2 from near Durban to Tsitsikamma National Park in South Africa; shallow coastal waters, no more than 30 meters deep

Max Size: Males mature 50cm, females 48 cm, maximum size unknown

Threats: Since the population size is small and contained within a restricted range, any threat will have an outsized impact. Habitat degradation from coastal development and rapid expansion of tourism and industry have likely impacted the happy chappie. The commercial prawn fishery may also pose a hazard to these sharks.

Points of Interest: Shysharks are so named because they curl into a ball and cover their eyes with their tails when threatened.

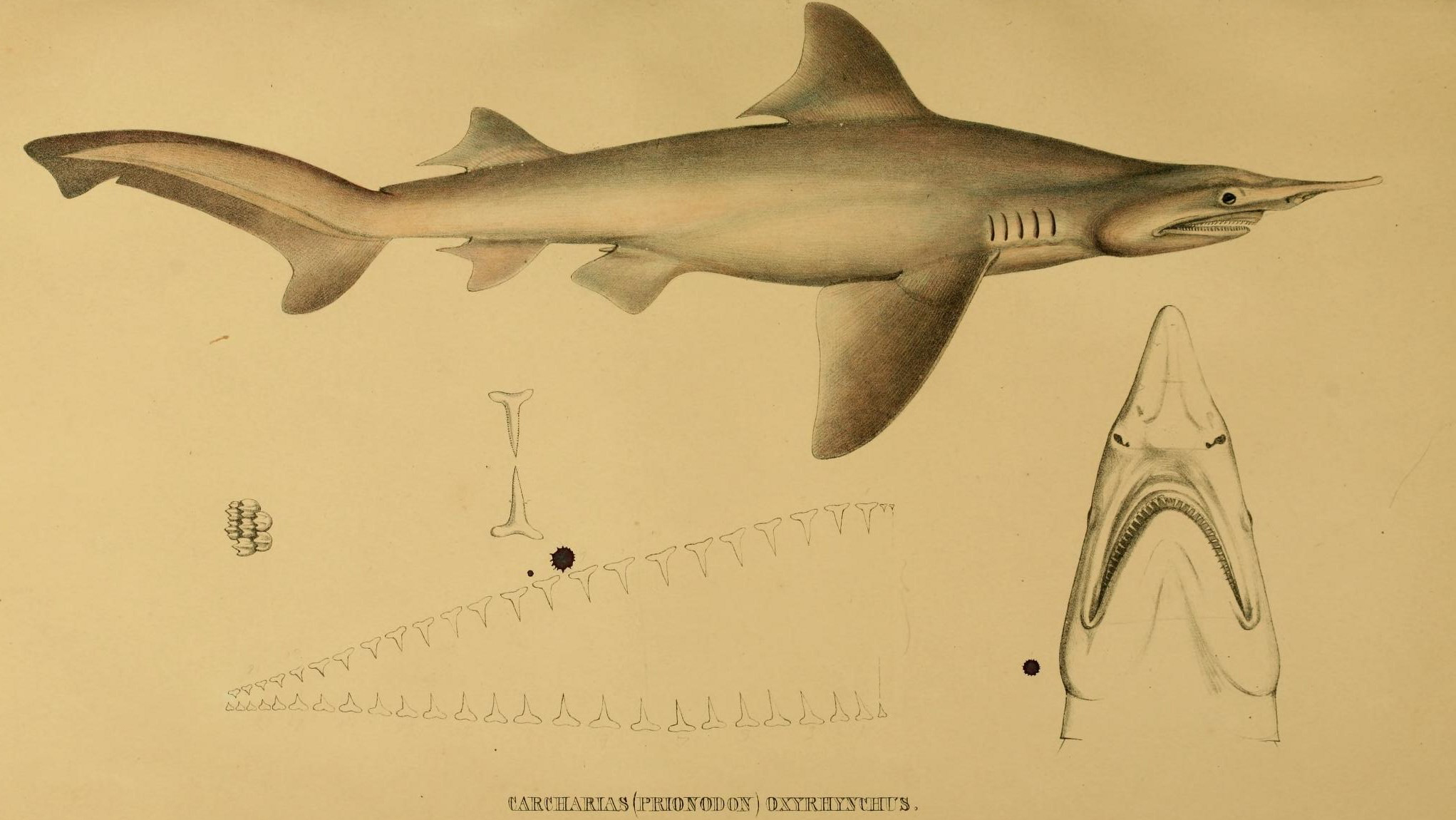

6. Daggernose Shark (Isogomphodon oxyrhynchus)

Habitat: Tropical west Atlantic as far north as Trinidad and Tobago to South America as far south as northern Brazil; turbid waters on wide continental shelves, nurseries in shallow waters and estuaries

Max Size: At least 152 cm long

Threats: Daggernose sharks are caught in gillnets used in artisanal fisheries, primarily as part of the bycatch in the Spanish mackerel fishery. Because their populations naturally grow very slowly even as compared to many sharks, they are vulnerable even when only caught at a low rate. One study found that the population would only be stable in a scenario with no fishing. They are listed as an endangered species in Brazil, but the laws designed to protect them are not well enforced. Populations are in steep decline and may already be collapsing.

Points of Interest: These sharks give birth to live young. They have three to eight pups in a litter after about one year of gestation. Mature females likely give birth every other year. Daggernose sharks feast on a diet of small, schooling fishes.

7. Striped Smooth-hound (Mustelus fasciatus)

Habitat: 1,500 km of coastline from southern Brazil to Argentina; floor of the inner continental shelf

Max Size: 155 cm long

Threats: Fishing pressure in their range is high – juveniles and pregnant females are often caught. In the 1980s high numbers of neonates (pups) were caught in gillnets. The number caught has gone down since then but not due to any effort to improve fishing methods or avoid catching them; instead, it is likely that fewer are caught because of a population decline.

Points of Interest: Females migrate from offshore to inshore waters to give birth to live young on a yearly cycle. Juveniles remain in the nursery grounds until they mature. Their diet consists mainly of shrimp and crabs. They are considered near extinction in Brazilian waters.

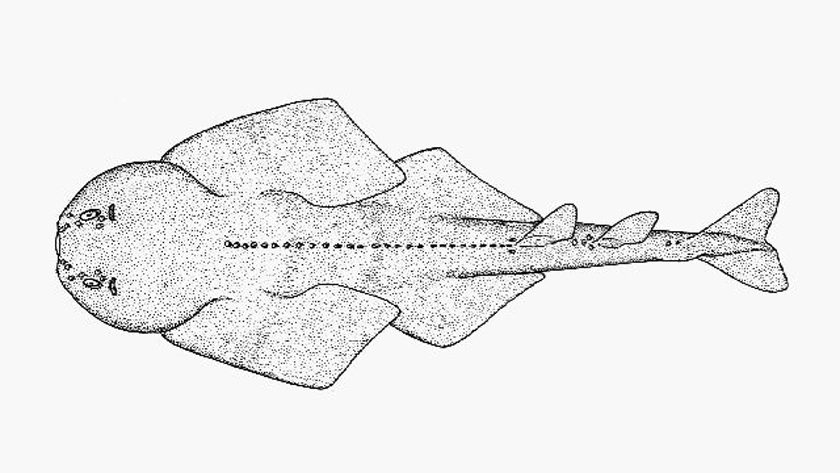

8. Angelshark (Squatina squatina)

Habitat: Scandinavia to northern Africa, most of the Mediterranean and Black Seas; day buried in the sand or mud, night near the ocean floor

Max Size: Male 183 cm, female possibly 244 cm

Threats: Intense fishing pressure has likely caused steep declines and local extinctions of angelsharks in much of their range. Most of the remaining population is in the Canary Islands where conservation planning is underway.

Points of Interest: Angelsharks give birth to live litters of 7-25 pups after a gestation of 8-10 months. Their diet is made up of bony fishes and species that live along the seafloor – and at least one angelshark is known to have eaten a cormorant. The Angel Shark Project has learned a great deal about angelsharks, including finding the location of one angelshark nursery and identifying the qualities of suitable angelshark habitat. This information was used to develop an action plan for the Canary Islands.

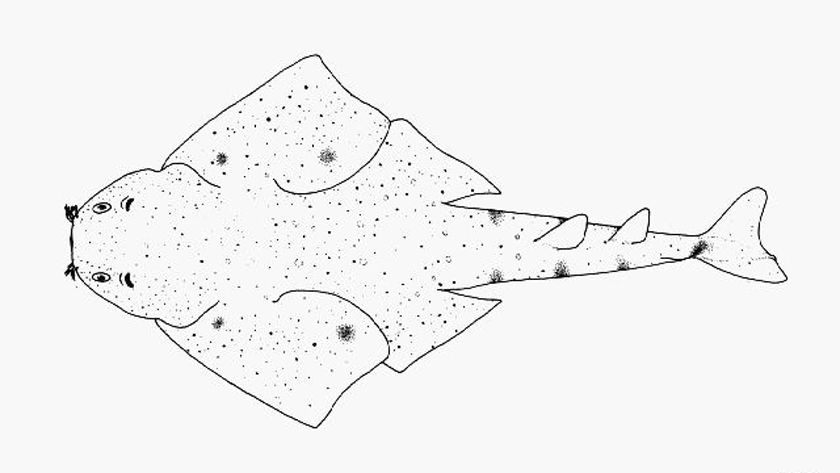

9. Sawback Angelshark (Squatina aculeata)

Habitat: East Atlantic and western Mediterranean; outer continental shelf, in the mud, at depths of 30-500m

Max Size: 188 cm

Threats: Like their relative the angelshark, they are threatened by intense fishing in the Mediterranean. They were commonly caught as bycatch until the 1980s, when reported catches became increasingly erratic.

Points of Interest: Sawback angelsharks eat small sharks, bony fishes, cuttlefish and crustaceans. Little else is known about them.

10. Smoothback Angelshark (Squatina oculata)

Habitat: East Atlantic & Mediterranean; continental shelves at a depth of 20-500m

Max Size: 160 cm

Threats: Like the other angelshark species above, they are threatened by intense fishing in the Mediterranean. Angelshark species are not differentiated from one another in reports by most Mediterranean fisheries, which makes tracking fisheries’ impact on each species difficult.

Points of Interest: Up to 100 smoothback angelsharks have been reported forming aggregations off the West African coast in December. They give birth to 3-8 pups. Their diet is made up of small fishes, cephalopods and crustaceans.

no more shark dieing i wanna become a marine bioligist and i say stop being 13 is hard enought and my babys my sharks are dieing by the minute sttttttttttttttttop the marine killing ok..

This is interesting! This is also awesome!

good job

hi me and my cousin, rye fleming are starting a bussiness called 36 down. We need some help getting started. We a currently working on a website now.

basiclly we research and study sharks then we find ways that we can try to save them so if you could help us get started or get our name out there that would be great!

thanks, lulu