Something was wrong with the snow leopard. The scientists watched as the tranquilizers kicked in and the cat sank down to the bottom of the cage. Moving closer, they realized that the young male was injured: his front-right leg was severed below the shoulder.

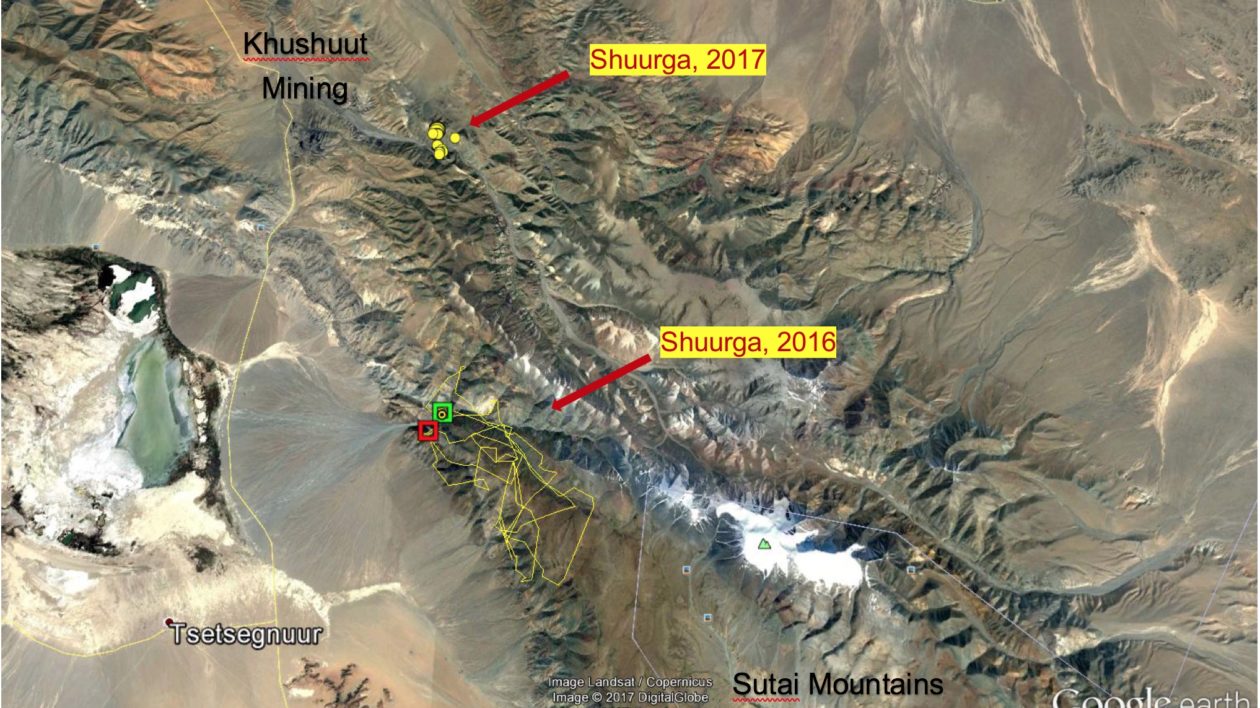

Here in western Mongolia’s Sutai Mountains, Nature Conservancy scientists are collaring snow leopards to better understand when and how they interact with local herders’ goats and sheep. These data will help design grazing plans that keep both leopards and livestock safe.

Tracking the Storm

Known as “the ghosts of the mountains,” snow leopards are found throughout Asia’s high mountain ranges. One of the most elusive big cats on earth, they are threatened by habitat degradation, poaching, and a decline in prey species due to competition with livestock.

Mongolia has about 1,000 of the world’s remaining leopards, clustered in the country’s south and west. In the Bumbat and Sutai Mountains, The Nature Conservancy is working with the Mongolian Academy of Sciences and Moscow State University to protect leopards and herders’ livestock. But to do so, they must first catch and collar leopards.

The scientists recognized this particular cat; in October 2016, they captured him in Khavtsgait Valley, about 30 kilometers to the southeast, and fitted him with a satellite collar. Caught amid a thunderstorm, they named him Shuurga, which means storm in Mongolian. But after just six months the signal from his collar went dark.

“Somehow he smashed his collar, and after March 2017 we didn’t get any signal,” says Bayarjargal Yunden, director of science for the Conservancy’s Mongolia program. And somewhere between then and now, he also lost a leg.

The team worked quickly. Laying Shuurga down gently on a mat, they fitted a new collar around his neck and gathered blood and genetic samples. The short stump that remained of his leg was still bloody and ragged, the wound was likely less than 2 months old, and bullet wounds grazed his back.

Shuurga is one of two collared leopards in the study; the second is a female leopard also collared in October 2016. The collars around their necks transmit a GPS location every hour, creating a detailed map of the leopards’ movements. “The data from these collars will help us understand where there are key points of interaction with livestock,” says Eddie Game, the Conservancy’s lead scientist for the Asia-Pacific region.

The Nature Conservancy is working with Mongolian herders to implement sustainable grazing practices. Yunden says that Mongolian herders traditionally moved their livestock each season, based on observation of pasture condition. They also reserved certain areas for winter pasture, keeping them ungrazed during the rest of the year to ensure an adequate winter food supply.

But the system broke down in the 1990s as Mongolia transitioned away from socialism. Yunden says the government dismantled the state herding collectives and privatized livestock ownership. Herders seeking more income increased their flocks, and the country’s livestock population jumped from 22 million in 1990 to 66.2 million by 2017.

“That resulted in overgrazing, land degradation and desertification, struggles between herders for grazing areas, and conflicts between livestock and wild animals,” explains Yunden.

Today, as part of a government conservation incentive program, communities can obtain exclusive grazing rights to an area of land if they create and enforce a grazing management plan.

“We’d like to incorporate snow leopards into these plans at a landscape scale,” says Game. “Ideally, we could identify the risky times for interaction, and work with the communities to design the grazing plan to minimize leopard-livestock interactions.”

Game says that conservationists don’t have a good understanding of how local leopards’ territories overlap with grazing areas, hence the need to gather data on the cats’ movements. The research team is also collaring two ibex, a common prey species for snow leopards, which will allow them to compare grazing areas for both livestock and the leopard’s wild prey.

And in 2015, Game and Yunden deployed more than 40 camera traps throughout the two mountain ranges to get a more accurate population assessment for the area. “It’s important to know that there’s a healthy population here,” says Game, “because it adds to the overall population assessment in Mongolia and confirms this as an important site.”

This type of integrated, community-based conservation is critical for snow leopard survival, because the species has large home ranges that are difficult to protect. Research shows that of the 170 protected areas in the snow leopard’s global range, 40 percent are smaller than the home range of a single adult male.

Finding Solutions for Human-leopard Conflict

As Shuurga’s injuries attest, human conflict is still a major challenge for snow leopard conservation. Game suspects that the cat caught his leg in an illegal marmot trap, and then either severed his limb in the struggle to get free, or suffered such a severe injury that the lower leg fell off.

The bullet marks are another mystery.

Since October, Shuurga’s second collar is working well, sending back detailed data on the cat’s movements. “There’s a mining site in the area, and Shuurga usually stays very close to the town where the workers live,” says Yunden. (The second cat, a 5-year old female, occupies a territory farther up the mountain.)

“We think that Shuurga’s injury makes it really hard for him to capture wild animals,” says Yunden, “so maybe it’s easier for him to catch livestock.” The bullet wounds could be the result of a herder defending their flock.

Retribution killing for livestock loss is another significant threat for snow leopards, but Game says that previous research indicates that levels of human-leopard conflict are comparatively low in Mongolia, where people tend to have larger herds. And research shows that leopards prefer natural prey species, even in areas where that prey is outnumbered by livestock.

“But at the same time, the snow leopard populations just isn’t that big,” says Game. The global population numbers between 7,500 and 8,000 individuals, about 1,000 of which are spread out across Mongolia. “With such a small population, you don’t have to lose that many leopards before it starts to make an impact,” he says, “especially if they’re isolated.”

Lack of awareness about leopard behavior is another problem. In addition to incorporating leopards into grazing plans, the Conservancy is working with the Snow Leopard Trust to help educate herders about leopards, in the hopes of reducing these killings.

“We need to work with herders to identify solutions,” says Yunden. “Without them it’s just not possible to protect these animals.”

create a fund to pay for livestock lost to snow leopard predation, similar to livestock/wolf compensation in the western US

Oh, it made me sad to see Shurga and I wondered how the cat stays alive. I’m glad to be part of the Nature Conservancy and learn how widespread is its activities. We need to keep Shurga injuries to a minimum.

Snow leopards are also found in Spiti valley of Himachal Pradesh.

https://raachotrekkers.com/spiti-snow-leopard-trail-winter-in-kinnaur-spiti/

The economics of snow leopard conservation are relatively simple: if the snow leopards and their wild prey are worth more than their livestock, the pastoralists will manage for maximum populations of the snow leopards and ibex [and other prey species]. Fortunately, the standard of living in Mongoloia is so low that very small amounts of western currency will be required to make the nomads wealthy nomads. There may be considerable advantage to providing payment to the nomads in kind rather than cash. A new horse, mobile home, 4×4 vehicle to pull the caravan, a motorcycle may be more valuable that cash to Mongolians. Let me say it again, let’s make Nomads Great Again by improving the environmental markets in Mongolia!!!

Many of our readers have expressed concern for the injured snow leopard, Shuurga, and asked questions about his well-being and chances of survival. I talked to our scientist, Eddie Game, who passed on the additional information below. We hope this addresses your questions and concerns.

From Eddie:

When our research team realized that Shuurga was injured, we did as much as we were legally allowed to do for him. The research team fully cleaned and sutured Shuurga’s leg before releasing him back into the wild.

It is reasonable to suspect Shuurga will have challenges hunting, but the reality is we simply don’t know how long snow leopards can survive with these types of injuries. I just checked the most recent GPS data and Shuurga is still moving around extensively and has clearly hunted successfully since he was capture last October.

People have reported seeing similarly trap-injured snow leopards before, but because these leopards are so elusive and live in such remote areas, we rarely ever find them after they’ve died. So, we don’t know how these types of injuries ultimately influence survival. Having a collar on Shuurga will help shed light on this, which may in turn help us work with the Mongolian government of policies and practices for cases like this in future.

I would like to know more of what happened to Shuurga, if they helped to heal her stumped leg and if they released her or put her on a reserve or something.