I’m constantly amazed by the opportunity for adventure and conservation, even in the most unexpected places.

This summer I had the good fortune to visit High Mountain Preserve to learn more about research into threatened northern long-eared bats found there. High Mountain is owned by The Nature Conservancy, the state of New Jersey, and Wayne Township. It’s situated in northern New Jersey, about 20 miles from New York City and right in the backyard of William Paterson University.

“People that live nearby, if they take care of their space, they take care of that wildlife,” says Laura Botero who spent the summer of 2016 with friends and fellow students Samantha (Sam) Craig and Dan Hansen camera trapping in High Mountain.

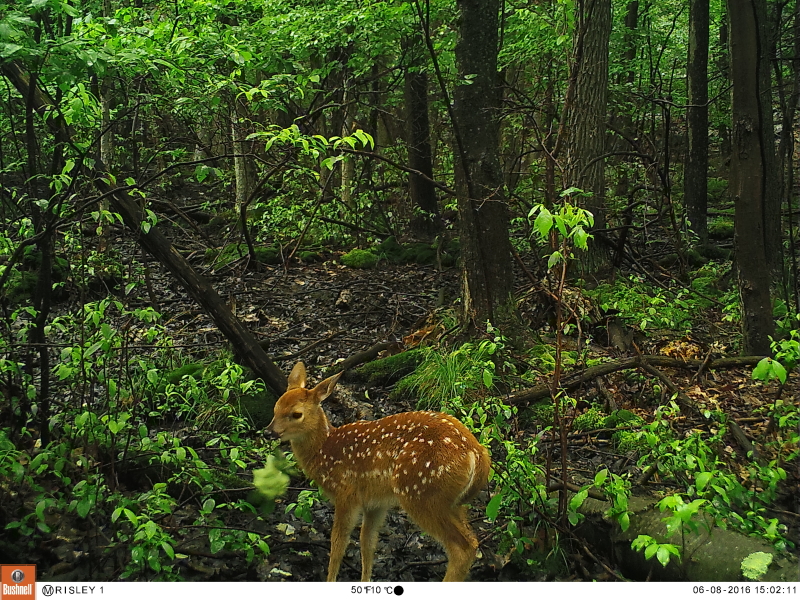

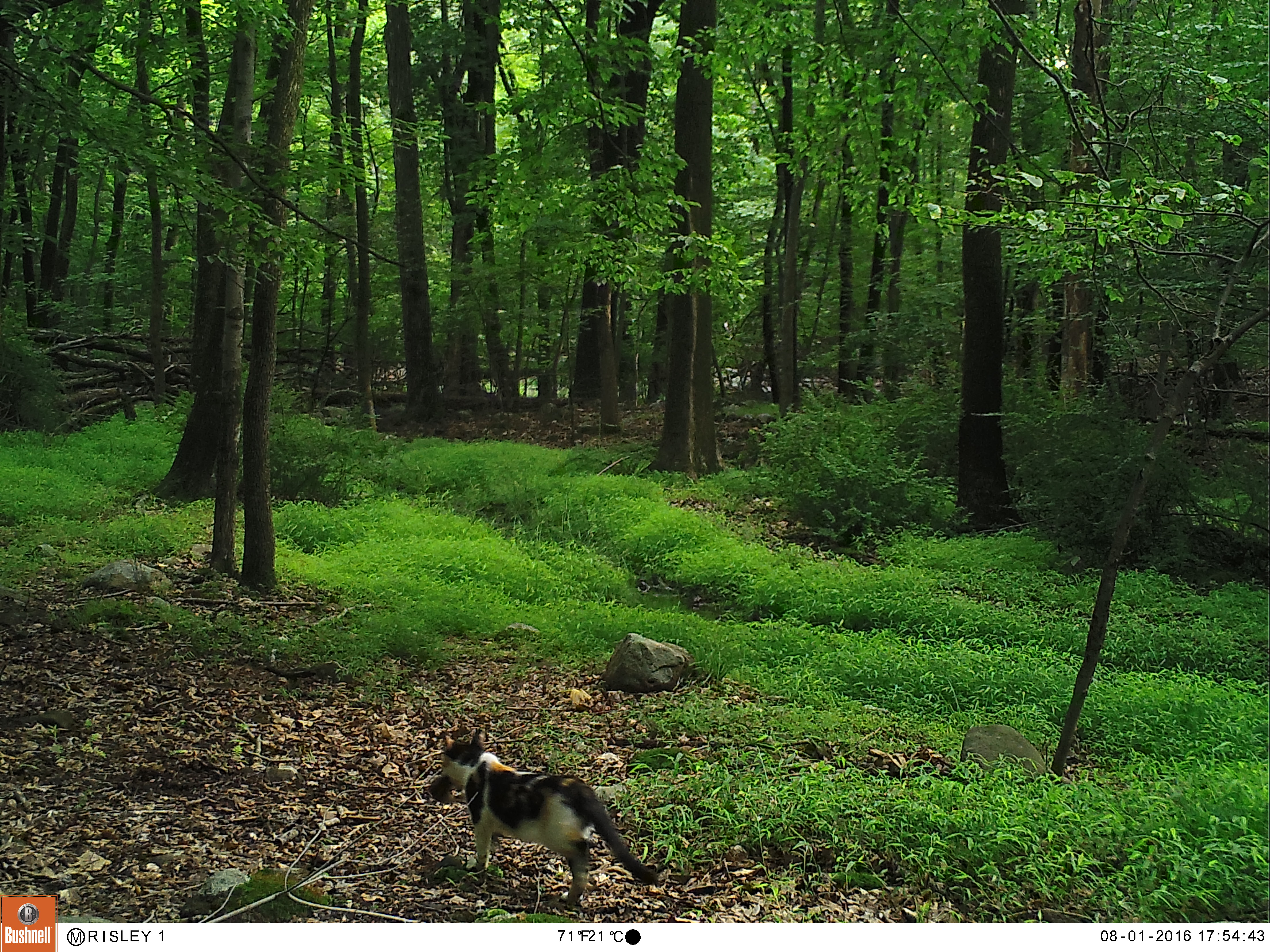

The students were inspired by Lance Risley, Professor of Biology’s passion for conservation science and wanted to lead a project with his guidance. Risley suggested that the students set up motion-activated camera traps to learn more about the wildlife on the preserve and see if cats are frequent visitors.

For two and a half months the students moved two camera traps around the 1,260-acre preserve, exploring every corner along the way. On average, they moved the cameras every two weeks. While setting the cameras up they were entertained by wildlife sightings including an owl being harried by smaller birds and a flying squirrel climbing up a nearby tree.

[simplechart id=”61484″]

Like so many places in the US, the wildlife of the preserve has yet to be fully documented. While the students didn’t find anything unexpected, their observations confirm that the preserve provides a refuge for foxes, turkeys, chipmunks, deer, and even rarer visitors like coyotes. They only saw two cats during the course of the project, one with what may have been a bird in its mouth; this was a lower incidence of neighborhood and feral cats than expected.

It made me more aware of myself and how I impact my surroundings — the way we take care of campus protects that forest.

Laura Botero

But data doesn’t have to be surprising to be valuable to science – the students showed that the preserve contains a wide array of wildlife typical of the region and is therefore of interest for further ecological study. Sometimes people assume that wildlife or nature are things to travel to see, overlooking the richness of natural areas and “common” species nearby.

“Every day that you’re hiking and you’re not hearing cars, you notice more,” says Laura. “I can’t believe all of this is here. It made me more aware of myself and how I impact my surroundings — the way we take care of campus protects that forest.”

For Laura, the importance of the project is not just in the record of wildlife found, but in realizing that even in the city our actions have the chance to help or harm wildlife. You don’t have to be an ecologist or professional conservationist to have an impact. For instance, the campus community helps keep High Mountain Preserve healthy by recycling, picking up trash, and taking steps to keep water clean — all things that we can each contribute to in our own neighborhoods.

Trail camera studies of wildlife aren’t limited to universities; you can participate too. Several citizen science projects rely on the public to identify wildlife from camera trap photos, and trail cams have gotten inexpensive enough that many people are setting them up on their property or in their neighborhood park (with proper public permits) to get a candid shots of the wild things that come out when we’re not around.

Camera Trap Highlights

I started using camera traps when they first came out in film not a big fan of digital one you got to spend a lot of money to get one that takes good night pictures never had that with film, just limited by the number of shots which was 24. You can get pictures of animals you could never get this one time I got a picture of a partial albino deer

It’s cool to see how the technology advances and gets smaller with better resolution. Thank you Julian! You might also be interested in this post about white deer: https://blog.nature.org/2016/02/03/white-deer-understanding-a-common-animal-of-uncommon-color/

I’m thinking the deer look awfully thin ! Are there any studies about their loss of habitat & how it’s effected their eating habits ? I know they eat plants and some barks from trees &, obviously, we’ve

mowed under a LOT of THAT over the past couple of decades.

Just curious.

Here in N.C. I just recently saw my first LIVE opossum in the woods. All others I’ve seen, raccoons, too,

have been Road Kill. Poor babies. Along with about 90% of the deer I’ve seen. I live just about 13 miles

north of Charlotte. It reminds me of living in Florida in the 90’s and literally watching the armadillo

disappear. When I got there, they were all over; you’d see one every morning on a walk. Then, more

and more dead in the road. Makes me SO unhappy !

Jane Guzauskas

Huntersville, NC

I wonder what that cat has in its mouth — bird or little mammal? And is it a feral cat or a house cat on the loose? Either way, it shouldn’t be there! Even when they’re well fed they will still stalk, toy with, and then kill prey. It’s their inborn nature to do so and the number of song birds, in particular, they destroy is terrible.